All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

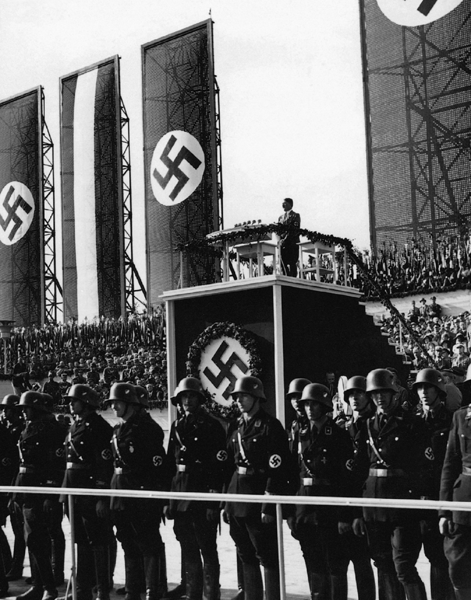

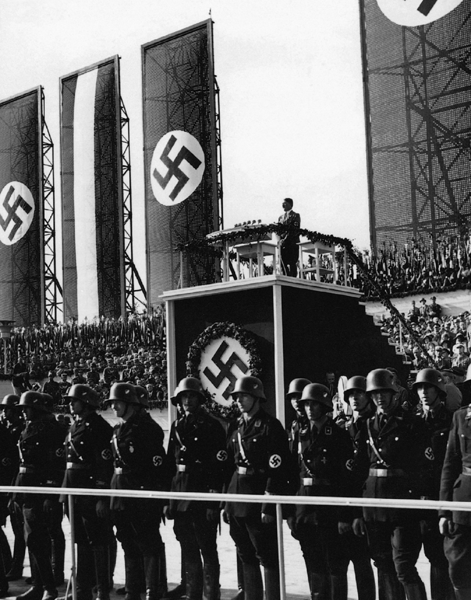

Adolf Hitler, Chancellor of Germany, addresses a rally at Tempelhof in Berlin in the mid-1930s. The SS men in the immediate foreground are members of his personal bodyguard, the Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler.

CHAPTER ONE

Like Nazi Germany itself, the roots of the 2nd SS-Panzer-Division Das Reich lay in World War I. Nazi ideology was fuelled by Germanys defeat, but the combat success of the Waffen-SS division drew on the lessons learned by the crack Stosstruppen in the last year of the war.

O n the morning of 21 March 1918, soldiers in the British 5th Army received an unpleasant surprise when an artillery bombardment began and pummelled their forward positions in an area near the Somme River. While German gunners hurled shells onto this section, small groups of lite, light infantry commandos crept past the British Armys front line, hidden by the morning fog and clouds of gas remnants. Armed with light machine-guns, portable mortars, flame-throwers, grenades and other weapons, these company and battalion-size units were known as the Sturmtruppen (storm troops) or Stosstruppen (shock troops).

When the artillery barrage ended, the storm battalions struck, using their weapons to disrupt communication and supply lines within the 5th Army and open wide gaps within the forward zone of the British defence network. This surprise action enabled General Oskar von Hutier and his 18th Army to advance 11.2km (7 miles) by the end of the day. Less than a week later, his forces seized the French rail centre of Montdidier and opened a gap 16km (10 miles) wide between the British and French armies. Thanks in part to the Stosstruppen, the German Spring Offensive of 1918 had a promising beginning, and seemed as if it might break the long stalemate that had prevailed along the Western Front during World War I.

FURTHER SUCCESS

On 9 April, another group of shock troops under the command of General Ferdinand von Quast routed a division of Portuguese soldiers during an assault on the Belgian rail centre of Hazebrouck. This operation enabled Quast and his 6th Army to advance 4.8km (3 miles) into enemy territory before being checked by the British 1st Army. Later in the month, the Germans occupied Passchendaele Ridge, and it seemed possible that they might achieve a breakthrough in Flanders.

On many earlier occasions, military commanders had used infiltration tactics to achieve decisive victory in the war. In September 1917, Hutier seemed to have perfected the effective deployment of storm troopers when he used them to capture the port of Riga from the Russians. A month later, General Otto von Below crushed the Italians at Caporetto using similar units. Late in November, a successful counter-attack by Stosstruppen commandos enabled the Germans to recapture Bourlon Wood near Cambrai. Suitably impressed with the results of these actions, General Erich von Ludendorff ordered Hutier and Below to use storm battalions on a large scale to inaugurate Operation Michael, the great spring offensive of 1918.

Ultimately, the spring offensive failed due to miscalculations made by Ludendorff, its chief architect, and the insufficient number of German forces available that were needed to exploit the initial successes achieved by the storm battalions and other units. In effect, it was the last bolt fired from the German war machine aimed at achieving a victory in World War I. Its failure ensured that the growing numerical superiority of the Allied armies would eventually force Germany into suing for an armistice and accepting the terms imposed by its enemies.

FELIX STEINER

Despite this unfavourable outcome, the effective deployment of the storm battalions gave some of the younger and more innovative members of the German officer corps the inspiration to construct a new military organization that would employ similar methods of mobility and infiltration against enemy forces. If this feat could be accomplished, they might be able to prevail when future conflicts engulfed Europe. One such officer was Second Lieutenant Felix Steiner, a decorated soldier who was disillusioned by the futility and waste of the static trench warfare he had experienced on the Western Front. In the aftermath of the war, he and other young reformers would develop an organization that would eventually be known as the Waffen-SS, the personal army of Adolf Hitler and his Nationalsozialistishe Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party, or NSDAP).

During the interwar period, Nazi protection squads known as the Schutzstaffel (SS) attracted volunteers from all over Germany, eventually enabling the SS organization to establish an armed paramilitary force with regimental-size units. By the outbreak of World War II, the Third Reich was able to organize these regiments into divisions. One such division would eventually be known as the Das Reich Division, or the 2nd SS-Panzer-Division Das Reich, a formidable collection of crack troops equipped with modern tanks, weapons and other equipment. As a military appendage of the NSDAP, it was the first, and one of the most effective, Waffen-SS divisions to develop from what was originally just a small cadre of bodyguards charged with the task of protecting Hitler and other Nazi political leaders.

If the lite storm battalions of World War I served as a model for a new German army for Steiner and other reform-minded officers, the divisive political atmosphere of post-war Germany created the environment that would draw zealous young men to the Nazi party and its uniformed, activist organizations. Unable to find satisfying explanations for their defeat in the conflict, many Germans found scapegoats to blame for the stab in the back that had led to the humiliating and (in their view) vindictive Versailles Peace Treaty imposed by the Allies. Such scapegoats included liberals, socialists, Jews and other elements in society that seemed unpatriotic. The fragile Weimar government was also an object of vilification and was widely seen as weak and corrupt.