I take my first look at the city again from the air, on my way to the Tom Jobim International Airport, named after one of Brazils most famous musicians. The flyover brings to my mind the dulcet, delicate, nostalgic voice that shapes the subtle, rhythmic instrumentation of bossa nova. The new trend, as the term loosely translates, of Brazilian music that flourished in the 1960s is an evocative blend of samba, jazz, and poetry. Jobim, along with Vinicius de Moraes, Joo Gilberto, Astrud Gilberto, and the American saxophonist Stan Getz, was fundamental in popularizing this new music form, the poetic vocals over a guitar track guided by a delicate drumbeat and typically augmented by another instrument playing a melody. It is as much a mood as it is a style, emanating subtle rhythm. The genres most famous song, and the first international hit, A Garota de Ipanema (The Girl from Ipanema), suitably expresses a nostalgic tale of love and desire set to a breezy beat that is so characteristic of bossa nova, a form that originated in Rio de Janeiro.

As the plane is about to land, though, I feel a long way from Ipanema. It is Saturday morning, and layers of hazy, tree-clad mountains rise up in the winter morning light, with jagged peaks and jungle far off in the distance. Below is the city, spreading out and coming into focus, with the Guanabara Bay visible in front, and the Atlantic Ocean a little further away. Welcome to Rio de Janeiro. To the north is the urban sprawl: busy roads, informal housing, hilltops dotted with dirt football pitches, and rooftops punctuated by blue water tanks. Touching down on the runway, I see the faded concrete of the airport, discoloured and stark, which contrasts with bossa novas romantic musical portrayal. Galeo Airport, as it is more commonly known, makes an impression, whether you are arriving for the first time or the fiftieth time, whether you are visiting or you live there. It is the entrance to, and initial point of contact with, the city, and the sensation on landing there is unmistakable. I hear a ladys sultry voice over the public address system, with its idiosyncratic flow of Portuguese, and see an antiquated airport that seems to be perpetually under renovation and yet still disorganized, non-intuitive, and outdated, a mix of the old and the new, the formal and the informal.

At once familiar and distant, the sentiments that the city elicits run deep. I am, and always will be, a foreigner here, and yet I feel emotively connected to this city. It goes far beyond the facile portrayal of an exotic or a tropical city; the experience is much more complex and nuanced than that. Jobim, and others, sing about the saudades that this city brings, a beautifully untranslatable term in Portuguese that defines this citys identity. Jobim was always struck by those saudades on seeing his beloved city again, as he sang in his song Samba do Avio (Airplane Samba). What is it that generates this plentiful and so idiosyncratically Brazilian sensation of saudades a complex emotive state of absence, melancholy, and nostalgiafor both locals and foreigners? The beauty of the city and its unique rhythm are somehow always accompanied by this sensation. At the airport, the bags were delayed, there were ongoing projects to upgrade and modernize the infrastructure, and the recently installed ceiling panels in passport control were already peeling despite the project still not being finished. As I waited around and then got lost in the airport, Tom Jobims music was in my head, its minor tones and delicate dynamics conjuring up conflicting images of the city, and I felt anxious in anticipation of what awaited me.

As with any city, there is much more to Rio de Janeiro than the stereotypes that are so commonly associated with it. When you arrive, the brutalist and isolating concrete architecture of the airport, with its discoloured, block lighting towers stained from the weather, has cracks and chunks missing, and grass and weeds could be seen coming up through cracks in the tarmac. There is an ongoing construction inside, with antiquated Exit signs and the dated, analogue weighing scales somehow harmoniously existing along with the brand-new, yet not quite finished, duty-free shops and escalators. The identifying dynamics of old and new are apparent not only in the physical structures but also in its personality and character. The customs official offered me a taxi, which belonged to his friend, which I declined; I was surprised, and the gesture reminded me of the unique experience in a city that I love. In one corner of the partially updated arrivals hall, whilst looking for the woman in the booth where I had to pay for a taxi and who asked if I would change some dollars for her, rested a couple of homeless men, topless, alongside the various construction projects. The dynamics of intense development and ideals of progress on the one hand, and relaxed nostalgia and a sense of stagnated timelessness on the other, define the character of the city in its modern history.

What is it about this place, I thoughtits incredible beauty, the natural landscape, its undeniable and corporeal attraction, the way in which it welcomes you with both visceral and expressive beauty. At the same time, the contrasts that exist between old and new, natural and urban, formal and informal, developed and underdeveloped, rich and poor, preservation and neglect, and so on are often abundantly clear and form an integral part of the citys identity. Rio de Janeiro has an appeal that comes from the abundant and varied sounds, sights, and experiences of the citys landscape. It is a place of stark sensorial stimulation.

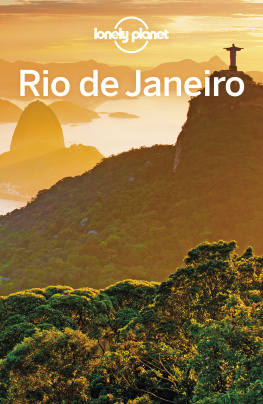

Having got into a taxi, I drive in through a section of Rios sprawling North Zone. I see the Complexo da Mar favela community with its multi-storey cinderblock houses underneath corrugated roofs delineated with busy, bustling streets. It is the neighbourhoods of the North Zone where most of Rios population lives, very different from the imposing gates and well-appointed apartment blocks of much of the South Zone (where Copacabana and Ipanema are) and the West Zone (the home of the Olympics), or from the high-rises downtown, or the crumbling old houses in the hilltop neighbourhood of Santa Teresa, which is my home every time I come to Rio. Moving down near the centre of the town, I am immediately immersed in the landscape that I remember so well; Rio, undoubtedly, possesses one of the most striking natural settings of any city (Fig.

Fig. 0

A map of Rio de Janeiro.. Hotel Glria.. Copacabana Palace.. The Ministry Building.. The Maracan

The jungle-clad hills rising up from the beaches that are caressed by the Atlantic Ocean are here, of course, a little further down the road, along with The Girl from Ipanema. For now, though, this was not the never-ending coastline or the Christ the Redeemer statue or Sugarloaf Mountain, sights that are so commonly invoked. Driving through the city, I pass close to the main Novo Rio (New Rio) bus terminal, built in 1965 and, like the airport, showing both creeping neglect and ongoing renovation in perpetual interaction. I see an urban space that incorporates busy, bustling highways punctuated by car horns, derelict buildings, and garbage by the side of the road. The multi-lane road dissects neighbourhoods where the houses are stacked one on top of the other, including some favela communities and some scrappy social housing projects. The Guanabara Bay, to my left, is polluted and uninviting. Something else has been happening, too, as was also apparent at the airport: clear signs of intense development and huge infrastructure projects, such as the redevelopment of the whole port area, new cable cars connecting hilly favela communities, and a Bus Rapid Transit system undergoing construction. It feels deeply in progress.