So many people have helped this project along the way that I barely know where to start. I do know that without Richard Fisher, editor at BBC Future, who commissioned the article on attention that led to the proposal for this book, the rest of it might never have happened. So thank you, Richard, for a crucial vote of confidence that got the ball rolling.

I am, of course, hugely grateful to the many scientists and their students who gave up their time, labs, and resources to help me experiment on myself, and who endured long periods of questioning and requests for information and research papers. Particular thanks go to Joe DeGutis and Mike Esterman at the Boston Attention and Learning Lab; Elaine Fox and her research team at Oxford University; Ernst Koster at Ghent University; Lila Chrysikou at the University of Kansas; Susan Wache, Peter Knig, and the feelSpace team; Klaus Gramann at TU Berlin; Russell Epstein, Steve Marchette, and the team at UPenn; John Wearden at Keele University; Marc Wittmann at the Institute for Frontier Areas in Psychology and Mental Health in Freiburg; and Amar Sarkar and Roi Cohen Kadosh at Oxford University for their help with my experiments. I had an absolute ball with you, and I hope that I have done justice to your research. Thanks, too, to Heidi Johansen-Berg at Oxford University, Martijn van den Heuvel from Utrecht University, Sara Lazar at Harvard University, and David Eagleman of Stanford University for some illuminating conversations along the way.

I feel very fortunate to have so many lovely friends around the world who were willing to put me up on my many research trips and allowed me to bang on about brains of an evening. To the Gosline-Knights in Boston, Neil Calderwood and Jessilyn Yoo in Berlin, Jolyon Bennett and Joanna Haigh in Oxford, and Valerie Jamieson in Didcot, thank you so much for having me, feeding me, and plying me with wine on the evenings when I wasnt having my brain zapped the next day.

Thanks also to my lovely, patient, and supportive friends and family at home for putting up with me, from the planning stages to the final written word. Special mentions must go to Cate for an incredibly well-timed mug purchase, and to Sally, Sole, Vanessa, and Ness for dangling cocktails in front of me at strategic points in the writing process.

Id also like to thank Jeannie Campbell for sharing her experiences with me and for many fascinating discussions about her experience of rebuilding her brain. I am also grateful to Gill Johnson for introducing me to meditation without worrying if you are doing it right.

I am hugely indebted to Peter Tallack and Tisse Takagi at the Science Factory, for believing in the project from the start and for brokering the deal that got the book written. To all at Scribe, particularly Philip Gwyn Jones and Lesley Halm, thank you for the opportunity to do this, and for asking all the right questions at all the right times.

And finally, to my wonderful husband, Jon. Without your support, encouragement, and incredible generosity with your air miles, none of this would have been possible. Thank you for your faith in me and your patience in allowing me what amounted to a second maternity leave. And to Sam, for proudly telling everyone that Mummy is an author, even when I didnt feel like one: thank you. I love you both.

For ease of reference, a log showing the times and dates of interviews and conversations can be found at the end of each chapter in which they were discussed. The interviews and conversations in the log are listed in the approximate order in which they are first mentioned in the chapter.

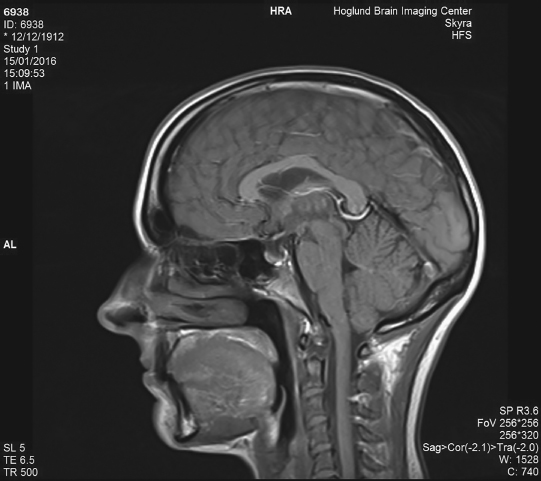

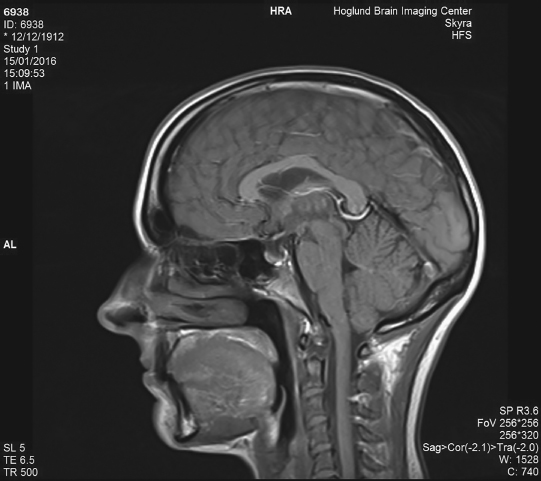

An MRI scan of the author's brain. (Courtesy of the University of Kansas)

Concentration is the root of all the higher abilities.

Bruce Lee

There's a lot about the brain that nobody knows for sure, but one of the few things that we do know is that focusing attention is about the most important thing that it does. Attention is the filter the brain uses to decide what is important and what can safely be ignoredand, without it, the lessons in front of your eyes wont get translated into real physical change, at the level of neurons and their connections to each other. So, if I want to make any meaningful change to my brain, good focused attention is going to be absolutely crucial.

Which might be a problem because leaving my luggage unattended in airports is just one example of the space-cadet tendencies that earned me the nickname butterfly brain when I was about eight years old. And this kind of thing still happens all the time. Recently, I was walking along the high street in my town when I looked over and saw my friend doubled up with laughter on the other side of the road. You look like a crazy lady, staring up at the sky and wandering aimlessly! she said. Charming. But she's right: when I zone out, I really zone out.

When it comes to getting my work done, this zoning out really doesnt help. I work at home, alone but for a very distracting dog, andin theoryin short, intense bursts while my young son is at school. Occasionally, this arrangement works perfectly, and I end the day feeling like Superwoman. More often than not, though, I spend the day flitting from one thing to the next, doing nothing of any use at alland although all I have to do is read a few scientific papers and send a few emails, I dont manage any of it. A few hours later, I am stressed, frustrated, and have even more to do the next day.

In brain terms, a lack of focus and a susceptibility to procrastination are two sides of the same cointhey are both hallmarks of a brain that is not under proper control of its owner. And Im not the only one who struggles with this problem. In one recent survey, 80 percent of students and 20 to 25 percent of adults admitted to being chronic procrastinators. Although we like to kid ourselves that all of this makes us more creative, the evidence suggests that it actually leads to stress, illness, and relationship problems.

Apart from anything else, letting the mind wander off doesnt seem to make us any happier. In another study, researchers interrupted people during the day to ask what they were doing and to score their level of happiness. They found that when people were daydreaming about something pleasant, it only made them about as happy as they were when they were on task. The rest of the time, mind-wandering actually made them less happy than they had been getting on with their work.

It was while I was banging my head on the desk in frustration one day that I remembered Joe DeGutis, a neuroscientist at Harvard University. We had spoken a few years before, for an article I was writing, and I knew that cognitive training in general, and attention in particular, was very much his thing. So I emailed him to see if he might be able to help sort me out. As it turned out, he and Mike Esterman, of Boston University, had been working on a combination of computer-based training and magnetic brain stimulation (also known as TMS) to help people focus better. So far, they had found that their program seemed to improve people's ability to sustain attention. Like in most neuroscience studies, they had only tried it on people with serious problemsfrom brain injuries, strokes, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). I couldnt help but wonder: might it work for me too?

Next page