Aaron Tugendhaft - The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet

Here you can read online Aaron Tugendhaft - The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: University of Chicago Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Aaron Tugendhaft

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-62353-5 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-73756-0 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-62367-2 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226623672.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tugendhaft, Aaron, author.

Title: The idols of ISIS : from Assyria to the internet / Aaron Tugendhaft.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020007574 | ISBN 9780226623535 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226737560 (paperback) | ISBN 9780226623672 (ebook)

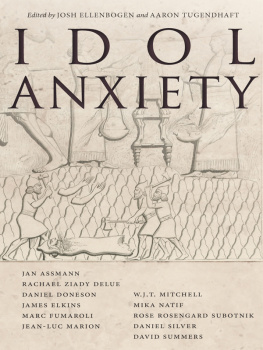

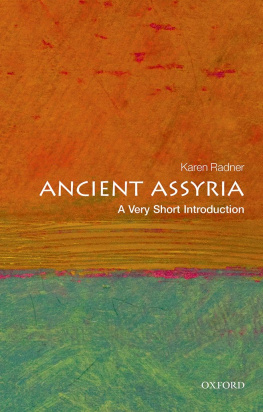

Subjects: LCSH: Mataf al-Mawil . | IS (Organization) | IconoclasmMiddle East. | Cultural propertyDestruction and pillageMiddle East. | Idols and imagesMiddle East. | Motion pictures in propaganda. | Mass media and propaganda. | Islamic fundamentalismMiddle East.

Classification: LCC N9103 .T84 2020 | DDC 700/.4820218dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020007574

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For my Iraqi family

The incapacity of Harun to restrain the followers of the Calf... was a wisdom from God made manifest in existence: that He be worshipped in every form.

Muhyi al-Din Ibn Arabi

Democracy has no monuments.... Its very essence is iconoclastic.

John Quincy Adams

Something is wrong. Its February 26, 2015, and Iraqi-born art historian Zainab Bahrani has just completed a lecture at NYUs Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. From the audience comes a voice, asking with some urgency what can be done to save Mesopotamian antiquities from destruction. What has provoked the question? I retreat to a corner to check my phone, and there it is: a video of men smashing sculptures in Iraqs Mosul Museum, posted repeatedly on my feed.

A bearded man dressed in the black taqiyah and white thawb of a devout Muslim addresses the camera. He stands before a fragment of a large Assyrian sculpture known as a lamassua protective deity that combines a bulls body, an eagles wings, and a human head.

Oh Muslims, the remains that you see behind me are the idols of peoples of previous centuries, which were worshipped instead of God, the man explains in Arabic, with the poise of a museum docent. The Prophet Muhammad commanded us to shatter and destroy statues. This is what his companions did when they conquered lands. Since God commanded us to shatter and destroy these statues, idols, and remains, it is easy for us to obey. We do not care what people think or if this costs us billions of dollars.

When he finishes, the video transitions to a museum gallery. Three men topple a life-sized sculpture from its pedestal. Others look on. In the ensuing montage men overturn sculptures, smash them with sledgehammers, and mutilate them with pneumatic drills. For two and a half minutes, these images of destruction are interspersed with shots of decimated sculptures strewn across the flooroften rendered in slow motion, lending the sequence a lyrical quality.

The audio is no less carefully crafted: A lone voice chants a Quranic verse and then the sound of a nashid weaves through the duration of the video. In haunting tones, the Arabic song declares: Demolish! Demolish! the state of idols / Hell is filled with idols and wood / Demolish the statues of America and its clan. Even for those who cannot understand the lyrics, the musicpunctuated by the sounds of shattering stone and machine-gun fireis mesmerizing.

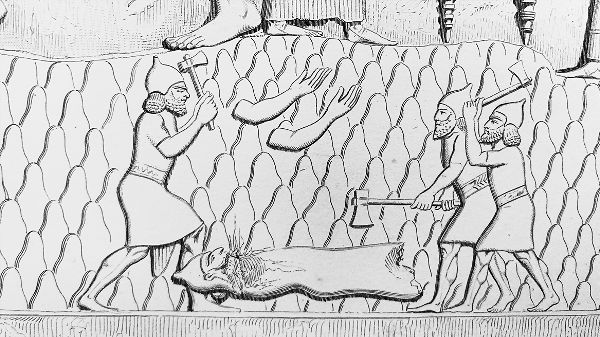

The video, I realized, bears an uncanny resemblance to a carved relief from the ancient Assyrian palace at Khorsabad, a town just north of Mosul. Both the video and the relief depict three men with sledgehammers smashing the toppled sculpture of a king (figures ). What is there to say about these two images separated by more than twenty-five hundred years yet only fifteen miles? Why this persistent drive to destroy imagesand to make other images showing their destruction?

Islamic State destruction in the Mosul Museum, Iraq. Video released February 26, 2015.

Three Assyrian soldiers smashing the sculpture of a king. Detail of a drawing by Eugne Flandin after a relief from Sargon IIs palace at Khorsabad (eighth century BCE). Paul-mile Botta, Monument de Ninive, 1849.

This book grew out of a personal connection to the latest events tearing apart Iraq. My grandfather was born in Baghdad in 1910, eleven years before the establishment of the modern state. He belonged to a Jewish community that had called the banks of the Tigris home since antiquity, and he grew up among the bookstalls and literary cafs that now survive only in memoirs. (I recommend Sasson Somekhs Baghdad, Yesterday.) This was a world in which Iraqi Jews lived side by side with Iraqis of other religions. They shared a common language and actively participated in shaping the new Iraq. But my grandfather also lived through the Farhud, the June 1941 pogrom that left nearly two hundred Jews dead and precipitated my familys departurefirst to Tehran, then Tel Aviv, and eventually New York. The unraveling of Iraqi pluralism that began with the departure of the Jews has continued to intensify. In the aftermath of the 2003 American-led invasion, Baghdads mixed neighborhoods gave way to rigorous segregation between Sunni and Shia. The forces of purity spread further when the Islamic State conquered Mosul in June 2014: Shia shrines were demolished; minority communities were butchered, enslaved, or made to flee their homes. The region seemed headed toward a homogeneity that it had not known since before the Tower of Babel.

In those foregone days after the flood, Genesis recounts, The whole earth was one language, one set of words (11:1). On the plains of Shinar, not far from modern Baghdad, all mankind sought to build a city and a tower with its top in the heavens in order to remain united. With technological prowess, they set to work baking mud into bricks. But God frustrated the plan by confounding their language such that they could no longer speak in one voice. The project came to a halt and the people dispersed.

On first reading, the biblical story seems antagonistic to the means and aims of political life. God opposes the human aspiration to live together in a city. But deeper scrutiny suggests that the people werent really building a political city.

Politics presupposes plurality. Its a strategy for reconciling opposing opinions and interests that grows out of a need to live together despite our different perspectives on the world. It attests to our ability to overcome differences without recourse to violence. Doing so is difficult, and often isnt pretty. Its what Max Weber famously called a strong and slow boring of hard boards. By contrast, the biblical story imagines a time when mankind didnt need politics. Already speaking as one, the people aspired only to prevent future dissent. Their city would be, not a political arena, but an infrastructure for enforcing unity. Babels builders built in the hopes of securing a world without politics.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet»

Look at similar books to The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Idols of ISIS: From Assyria to the Internet and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![Nietzsche - Twilight of the Idols [N.F. - Philosophy]](/uploads/posts/book/249935/thumbs/nietzsche-twilight-of-the-idols-n-f.jpg)