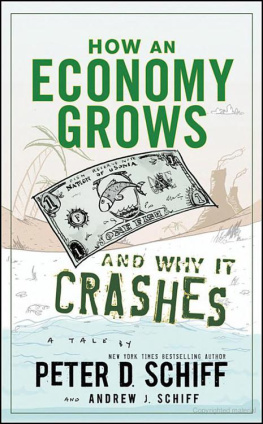

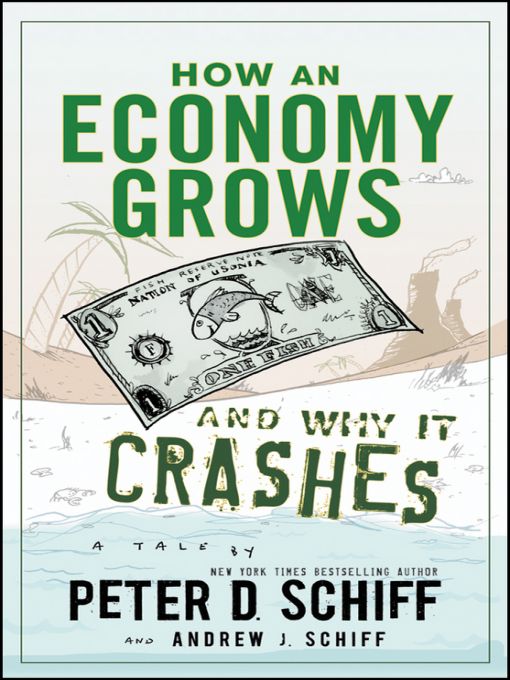

Table of Contents

To my father Irwin Schiff and fathers

everywhere who tell stories to their sons, and to

my son Spencer and sons everywhere who pass

them on to subsequent generations.

Peter

To Irwin for the logic, Ellen for the care and

support, Ethan for the enthusiasm, Eliza for

the wonder, and Paxton for the home (maybe

one day well get the hearth).

Andrew

DISCLOSURE

In addition to being the president, Peter Schiff is also a registered representative and owner of Euro Pacific Capital, Inc. (Euro Pacific). In addition to his duties as director of communications, Andrew Schiff is also a stock broker at the firm. Euro Pacific is a FINRA registered Broker-Dealer and a member of the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC). This book has been prepared solely for informational purposes, and it is not an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation to buy or sell, any security or instrument, or to participate in any particular trading strategy.

AUTHORS NOTE

In this allegory of U.S. economic history the reader will encounter many recognizable personalities and events. But as a very broad brush was needed to condense such a complex story into a cartoon book, many details have been blended.

In addition to the exploits of specific historical figures, characters represent broader ideas. For instance, while Ben Barnacle is clearly our version of Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, Barnacles actions in the story are not meant to solely apply to Bernanke himself. Rather, he is a representative of all highly inflationary economists.

In real life, Federal Reserve Notes were introduced 20 years before the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. But given his penchant for spending, we decided to credit him with the innovation. And although Chris Dodd was but a child when Fannie Mae was actually created, his support of the agency in later years gives him originator status in our story. And, although the foreign islands in the book roughly correspond with actual countries, they are also stand-ins for all nations.

We ask that you forgive us these, and other, liberties of chronology and biography.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past century or so, academics have presented mankind with spectacular scientific advancements in just about all fields of study...except one.

Armed with a mastery of mathematics and physics, scientists sent a spacecraft hundreds of millions of miles to parachute to the surface of one of Saturns moons. But the practitioners of the dismal science of economics cant point to a similar record of achievement.

If NASA engineers had evidenced the same level of forecasting skill as our top economists, the Galileo mission would have had a very different outcome. Not only would the satellite have missed its orbit of Saturn, but in all likelihood the rocket would have turned downward on lift-off, bored though the Earths crust, and exploded somewhere deep in the magma.

In 2007 when the world was staring into the teeth of the biggest economic catastrophe in three generations, very few economists had any idea that there was any trouble lurking on the horizon. Three years into the mess, economists now offer remedies that strike most people as frankly ridiculous. We are told that we must go deeper into debt to fix our debt crisis, and that we must spend in order prosper. The reason their vision was so poor then, and their solutions so counterintuitive now, is that few have any idea how their science actually works.

The disconnect results from the nearly universal acceptance of the theories of John Maynard Keynes, a very smart early-twentieth century English academic who developed some very stupid ideas about what makes economies grow. Essentially Keynes managed to pull off one the neatest tricks imaginable: he made something simple seem to be hopelessly complex.

In Keyness time, physicists were first grappling with the concept of quantum mechanics, which, among other things, imagined a cosmos governed by two entirely different sets of physical laws: one for very small particles, like protons and electrons, and another for everything else. Perhaps sensing that the boring study of economics needed a fresh shot in the arm, Keynes proposed a similar world view in which one set of economic laws came in to play at the micro level (concerning the realm of individuals and families) and another set at the macro level (concerning nations and governments).

Keyness work came at the tail end of the most expansive economic period in the history of the world. Economically speaking, the nineteenth an early-twentieth-century produced unprecedented growth of productive capacity and living standards in the Western world. The epicenter of this boom was the freewheeling capitalism of the United States, a country unique in its preference for individual rights and limited government.

But the decentralizing elements inherent in free market capitalism threatened the rigid power structures still in place throughout much of the world. In addition, capitalistic expansion did come with some visible extremes of wealth and poverty, causing some social scientists and progressives to seek what they believed was a more equitable alternative to free market capitalism. In his quest to bring the guidance of modern science to the seemingly unfair marketplace, Keynes unwittingly gave cover to central authorities and social utopians who believed that economic activity needed to be planned from above.

At the core of his view was the idea that governments could smooth out the volatility of free markets by expanding the supply of money and running large budget deficits when times were tough.

When they first burst onto the scene in the 1920s and 1930s, the disciples of Keynes (called Keynesians), came into conflict with the Austrian School which followed the views of economists such as Ludwig von Mises. The Austrians argued that recessions are necessary to compensate for unwise decisions made during the booms that always precede the bursts. Austrians believe that the booms are created in the first place by the false signals sent to businesses when governments stimulate economies with low interest rates.

So whereas the Keynesians look to mitigate the busts, Austrians look to prevent artificial booms.

In the economic showdown that followed, the Keynesians had a key advantage.

Because it offers the hope of pain-free solutions, Keynesianism was an instant hit with politicians. By promising to increase employment and boost growth without raising taxes or cutting government services, the policies advocated by Keynes were the economic equivalent of miracle weight-loss programs that required no dieting or exercise. While irrational, such hopes are nevertheless soothing, and are a definite attraction on the campaign trail.

Keynesianism permits governments to pretend that they have the power to raise living standards with the whir of a printing press.

As a consequence of their pro-government bias, Keynesians were much more likely than Austrians to receive the highest government economic appointments. Universities that produced finance ministers and Treasury secretaries obviously acquired more prestige than universities that could not. Inevitably economics departments began to favor professors who supported those ideas. Austrians were increasingly relegated to the margins.