David Kaiser and W. Patrick McCray

D. Graham Burnett

Cyrus C. M. Mody

Michael D. Gordin

W. Patrick McCray

David Kaiser and W. Patrick McCray

groovy \gru-vi\ adj 1: marvelous, wonderful, excellent. 2: hip, trendy, fashionable.

Something was happening. Otherwise, why would Theodore Roszak be agreeing with Edward Teller? What could the left-leaning history professor and favorite of Berkeley-area coffeehouse radicals possibly have in common with a nuclear-weapons designer whose dark visions helped inspire Stanley Kubricks sinister Dr. Strangelove? Something was happening. But what was it?

As the 1970s began, Teller and Roszak were about as far apart politically as two men could possibly be. Yet they found some quantum of concordance in their assessment that young Americans were relating to science and technology in a manner very different from that of just a decade earlier. When he surveyed the development of science in the United States since 1945, Teller concluded that all is not well. The problem was especially acute among our young people, for whom thorough and patient understanding is no longer considered relevant. To Tellerthe very apotheosis of the military-industrial complexthis endemic lack of interest was the surest sign of decadence.

Roszak concurred. As he wrote in his 1969 book, The Roszaks counterculturea monolithic term he deployed to capture what was actually an inchoate collection of individuals, interests, and ideologieswas antirationalist and opposed to both sterile technocracy and impersonal Big Science. Instead of astrophysics, engineering, or molecular biology, youthful members of the counterculture, Roszak held, were more likely to embrace astrology, Eastern religions, and chemically enhanced spirituality.

Starting from opposite ends of the political spectrum, Teller and Roszak both arrived at a common diagnosis: by the late 1960s, American youthand American society in generalhad turned away from the science and technology that had underpinned the expansion, power, and prosperity of the United States since 1945. But Roszak and Teller were wrong in their assessment. Americas youth had not turned away wholesale from science and technology. Everyone from vocal campus radicals to members of Nixons silent majority could see that a new type of science, a new way of engaging with technology, was emerging. Something new was percolating from 1970s-era dorm rooms, zine publishers, hot tubs, and experimental communities. This book explains what and why.

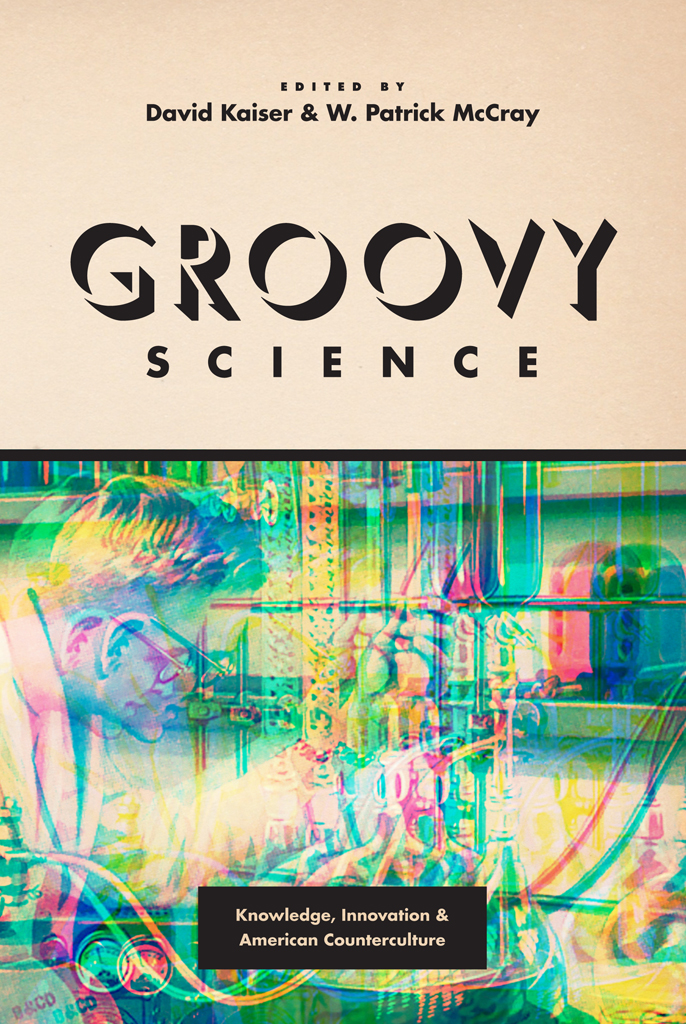

Our argument in this edited collection is that members of many strands of the American counterculture, although wary of a larger society that seemed to prize conformity, consumerism, and planned obsolescence, were not antiscience. Rather, we argue, many young people who self-identified as part of the counterculture in the United States, stretching from the late 1960s through the early 1980s, dismissed examples of science and technology that struck them as hulking, depersonalized, or militarizeda rejection of Cold Warera missiles and mainframes rather than of science and technology per se. Instead of the traditional science and technology promulgated by giant government programs, defense contractors, and corporate research labs, the counterculture embraced something new and different. We call this alternative groovy science.

Indeed, this books cover art reflects the blend of the conventional and the countercultural. Here is a stereotype of an Establishment scientistwhite, male, hair closely cutbut his activities are blurred, distorted, and shifted by colorful, sometimes polarizing, and often groovy forces emanating from outside the lab.

Some of the most iconic, colorful, and controversial figures in the American countercultural movements were enamored of modern science

We therefore borrow the term groovy to label this cluster of activities and aspirations. Originally a slang term used by African American jazz musicians in the 1930s and 1940s, by the late 1960s the word had become more closely associated with hippies and counterculture. The songwriting duo Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel released their 59th Street Bridge Song (also known as Feelin Groovy) in 1966; a few years later the Grateful Dead produced a cover. In 1971 a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California explained in The Underground Dictionary that among the largely white, middle-class celebrants of American counterculture, groovy had come to mean great, fantastic, joyful, happy. The term faded from common usage during the 1980s, and hence it provides a useful marker for the long 1970s on which we focus here.

The essays in this volume do not aim to cover all aspects of the history of science in the United States during the 1970s. Rather, they lay a foundation for addressing the shifting practices and cultural valences of science and technology during this recent and underexplored period. Examples of groovy science can be found among mainstream researchers who sought ways to engage with different communities and nontraditional forms of science, as well as among fringe thinkers who sought a place in the mainstreams spotlight. Groovy science, in other words, reflects the social exploration, experimentation, and eclecticism that were emblematic of the counterculture(s) during one of the most colorful periods of recent American history. To further characterize groovy science, we have highlighted four themes, around which this volume is organized: