APPENDIX A

A Note on the Dates Used in This Work

T here are many old saws about archaeologists. One that we have seen on a bumper sticker is, Archaeologists are romantic: they will date any old thing. But corny jokes sometimes make a serious point: dates and dating techniques take up a great deal of space in archaeological textbooks for good reason. Without a chronological framework it is impossible to discuss cultural change or test hypotheses to explain past events. If one does not know which of several archaeological cultures is earlier than another, or whether several cultures existed at the same time, it is impossible to untangle the web of cause and effect.

It is widely assumed that in a given geographic area such as Greece there has been a long, slow domino effect: that is, earlier cultures affected the evolution of later ones. The selection of a good site for a settlement in the Neolithic, for instance, increased the probability that the same site would play an important role in later periods. If nothing else, the ruins visible at an earlier site advertised its advantages and disadvantages to later generations. Any attempt to work out the proper sequence of historically related events, therefore, requires a firm understanding of chronology.

Until the advent of nuclear physics in the second half of the twentieth century, the age of ancient things was determined by relative dating. Individual artifacts and buildings were dated within a single site by their stratigraphic positionthat is, whether they were near the top or bottom of a series of layers. In an undisturbed sequence of archaeological layers, artifacts were assumed to be progressively older as one descended through the layers. Dating between sites was achieved primarily by cross-dating. That is, if artifacts found at the top of site A were identical to artifacts from the bottom of site B (as long as they were geographically close and the respective sequences of layers were undisturbed), it followed that site A was probably older, relatively speaking, than site B.

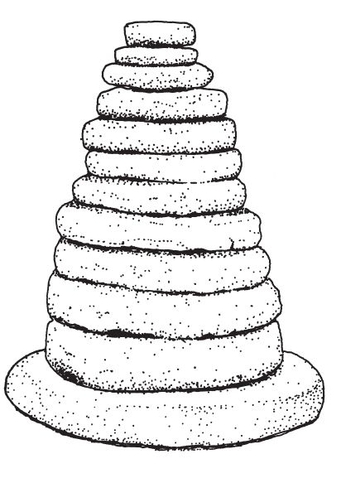

A.1 A stack of lead weights from Late Bronze Age Akrotiri on Santorini.

Another form of relative dating was achieved by cross-dating: relating Greek sites to the more established chronologies of the neighboring cultures of pharaonic Egypt and Mesopotamia, which are based on astronomical dates and king lists. Cross-dating depends on finding objects of a known date from one culture in one level of another. Thus a well-dated Egyptian artifact from a known dynasty when found in a stratum of a Minoan or Mycenaean site can be used to establish the date of that stratum, assuming that the Egyptian artifact is not an heirloom or antique (always a risky assumption). Key cross-dates were established in this way early in Aegean Bronze Age archaeology, and they still underpin the entire chronology of the period.

Precise calendar dates, or absolute dates, for sites and artifacts can sometimes be determined using more scientific techniques. The most widely used methods of absolute dating in archaeology today measure radioactive decay; these are called radiocarbon dating (also 14C or carbon-14 dating), thorium/uranium dating, or potassium/argon dating. Other dating techniques, such as electron spin resonance and thermoluminescence, employ related physical processes. Another absolute dating technique is dendrochronology, which involves the counting of tree rings. The technical details of these and other methods are too numerous to include here, but the interested reader can pursue them in some of the references cited in the Bibliographic Essay. The two systems of dating, the absolute and the relative methods, have been used together over the past century to build up the established chronology for the prehistoric archaeology of Greece. The dates given in this book for the Stone Age are largely based on absolute dating. Dates for the Bronze Age have largely been determined by the more traditional relative dating method.

Calendar dates are expressed in the literature in a variety of ways, and confusion can arise when different systems are used by different archaeologists. Throughout this work we have attempted to use a reasonably consistent system, but it differs from that used in other books, and the dates will not always match those in museum exhibits and guides. The discrepancies reflect the inevitable refinement of chronology as methods are improved and new samples are obtained. We have chosen to use the system of B.P. (before present) dates, which is widely used in the natural sciences to express dates in the Old Stone Age. By international convention, present is defined as A.D. 1950. Hence, a date of 5000 B.P. means 5,000 years before 1950. In this book, B.P. dates from before about 40,000 years ago are rough approximations only, not precise calendar dates. The B.P. dates given for Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic sites, however, are based on dendrochronology, radiocarbon dating (itself calibrated using dendrochronology), and other means, which are expressed as true calendar dates, although there is a certain margin of error for any date.

We use a different system for the Bronze Age. Although archaeology has developed a good sequence of relative dates for the Bronze Age Aegean, by convention they are expressed as B.C. or B.C.E. (before Christ or before the common era), counting backward from 2,000 years ago. Hence, a culture that began in 4000 B.P. (4,000 years ago) is dated 2000 B.C. in this system. Because the B.C. system is used universally by writers on the Aegean Bronze Age and is found in museum guides, display captions, and in textbooks, we use it here for convenience.

There is a useful logic, however, in using the B.C. designation for Bronze Age dates. Because the Bronze Age chronology is largely a conventional one based on relative dating, and the Stone Age chronology is primarily an absolute system, the change from B.P. to B.C. largely coincides with the change in the predominant system of dating. No matter how a chronology has been built up, some statistical uncer-tainty still underlies all dates, and as a consequence we sometimes add the qualifier ca. (circa, or about) before many dates, and the reader may wish to add that mentally to all of them. These rather loose frameworks of dating may not seem sufficiently precise, but despite enormous scientific advances, events of long ago sometimes can be dated only within very broad ranges.

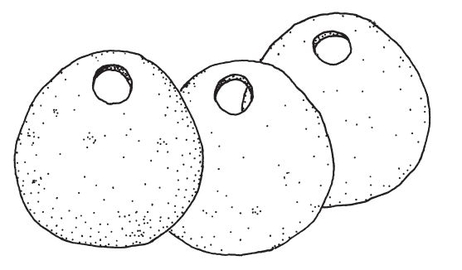

A.2 Terra-cotta loom weights perforated for suspension from the warps of an upright loom.