Charles O. Hucker - Two Studies on Ming History

Here you can read online Charles O. Hucker - Two Studies on Ming History full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Kenneth G. Lieberthal and Richard H. Rogel Center for Chinese Studies, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Two Studies on Ming History

- Author:

- Publisher:Kenneth G. Lieberthal and Richard H. Rogel Center for Chinese Studies

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Two Studies on Ming History: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Two Studies on Ming History" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Two Studies on Ming History — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Two Studies on Ming History" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES

MICHIGAN PAPERS IN CHINESE STUDIES

Ann Arbor, Michigan

TWO STUDIES ON MING HISTORY

by

Charles O. Hucker

Professor of Chinese and of History

The University of Michigan

Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies

No. 12

1971

Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program

Copyright 1971

by

Center for Chinese Studies

The University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-89264-012-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-472-03811-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-472-12757-3 (ebook)

ISBN 978-0-472-90152-4 (open access)

The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

CONTENTS

[Prepared for an August 1969 research conference on. Chinese military history sponsored jointly by the American Council of Learned Societies and the East Asian Research Center of Harvard University; to be included in Frank A. Kierman, Jr. and John K. Fairbank, editors, Chinese Ways in Warfare (in preparation)]

[Originally published in Silver Jubilee Volume of the Zinbun-Kagaku-Kenkyusyo, Kyoto University (Kyoto, 1954), pp. 224256]

In the spring and summer of 1556 a renegade Chinese named Hs Hai  led an invading group of Japanese and Chinese on a plundering foray through the northeastern sector of Chekiang province. Opposing them was a military establishment that for years past had been battered by coastal raiders, now under the control of an ambitious and clever civil official named Hu Tsung-hsien

led an invading group of Japanese and Chinese on a plundering foray through the northeastern sector of Chekiang province. Opposing them was a military establishment that for years past had been battered by coastal raiders, now under the control of an ambitious and clever civil official named Hu Tsung-hsien  In 1556 the raiders besieged cities and ravaged the countryside, defeated and terrorized the government soldiery in a series of skirmishes and battles, and accumulated booty and captives. Hu Tsung-hsien resorted to guile more than to force, turned the marauding leaders against one another, baited them with bribes and promises, and finally cleared the area of them. The campaign was not one of the most consequential in Chinas military history, even during the Ming dynasty (13681644). But it was famous and well reported in its time, and it illustrates some of the unusual ways in which the Chinese of the imperial age coped with the often unusual military problems they faced.

In 1556 the raiders besieged cities and ravaged the countryside, defeated and terrorized the government soldiery in a series of skirmishes and battles, and accumulated booty and captives. Hu Tsung-hsien resorted to guile more than to force, turned the marauding leaders against one another, baited them with bribes and promises, and finally cleared the area of them. The campaign was not one of the most consequential in Chinas military history, even during the Ming dynasty (13681644). But it was famous and well reported in its time, and it illustrates some of the unusual ways in which the Chinese of the imperial age coped with the often unusual military problems they faced.

. Over the preceding centuries the Chinese had grown accustomed to three major kinds of military challenges: (1) domestic disturbances created by discontented subjects, which at their strongest threatened and sometimes achieved changes of dynasties; (2) probing raids or occasional massive invasions of highly mobile northern nomadic peoples; and (3) resistance of southern and southwestern aboriginal tribesmen to the steady spread of Chinese settlement and sociopolitical organization. Against these potential challenges, both from within and from without, Chinese governments had come to put great faith in the suppressive influence of the awesome air of moral superiority that emanated from their sprawling civil officialdom. But behind the facade of self-righteous gentility there always were large armies in walled garrisons strung behind the Great Wall across northernmost China or spotted elsewhere at strategic points along important water and land routes. In face of all dangers, Chinese government policy fluctuated between two types of actions: (1) military initiatives to break up threatening confederations, to seize natural staging areas, or to keep the enemy off balance by shows of force; and on the other hand (2) diplomatic initiatives to mollify, threaten, cajole, confuse, or distract the enemy so that Chinas security was not likely to be endangered.

When hostilities erupted, whether on the frontiers or in the interior, the government traditionally considered two possible responses: (1) a straightforward military solution, called "extermination ( chiao  or mieh

or mieh  or (2) an indirect politico-economic solution, called "pacification ( chao-an

or (2) an indirect politico-economic solution, called "pacification ( chao-an  chao-fu

chao-fu  or similar terms suggesting "summoning and appeasing), supported by real, but muted, threats of military action. In their pragmatic way, Chinese officials seem normally to have considered direct military solutions suitable only in the last resort, when the nations vital interests were at stake and pacification was impossible or would yield unacceptable results. Except in the cases of notoriously bellicose Chinese leaders, pacification seems to have been greatly preferred as the normal means of coping with the disaffected. This preference no doubt reflects Chinese inclinations within the family and local community to "keep things going" at almost all costs, by mediating, compromising, and saving face all around.

or similar terms suggesting "summoning and appeasing), supported by real, but muted, threats of military action. In their pragmatic way, Chinese officials seem normally to have considered direct military solutions suitable only in the last resort, when the nations vital interests were at stake and pacification was impossible or would yield unacceptable results. Except in the cases of notoriously bellicose Chinese leaders, pacification seems to have been greatly preferred as the normal means of coping with the disaffected. This preference no doubt reflects Chinese inclinations within the family and local community to "keep things going" at almost all costs, by mediating, compromising, and saving face all around.

Even before that time coastal raiding had been resumed on an ever increasing scale, and it reached and passed its peak in the 1550s. (This happened to be just the time when West European coasts, and especially shipping lanes, were being similarly harassed by marauders from the Barbary Coast of Africa.)

Chinas efforts to cope with these coastal marauders were complicated by several factors:

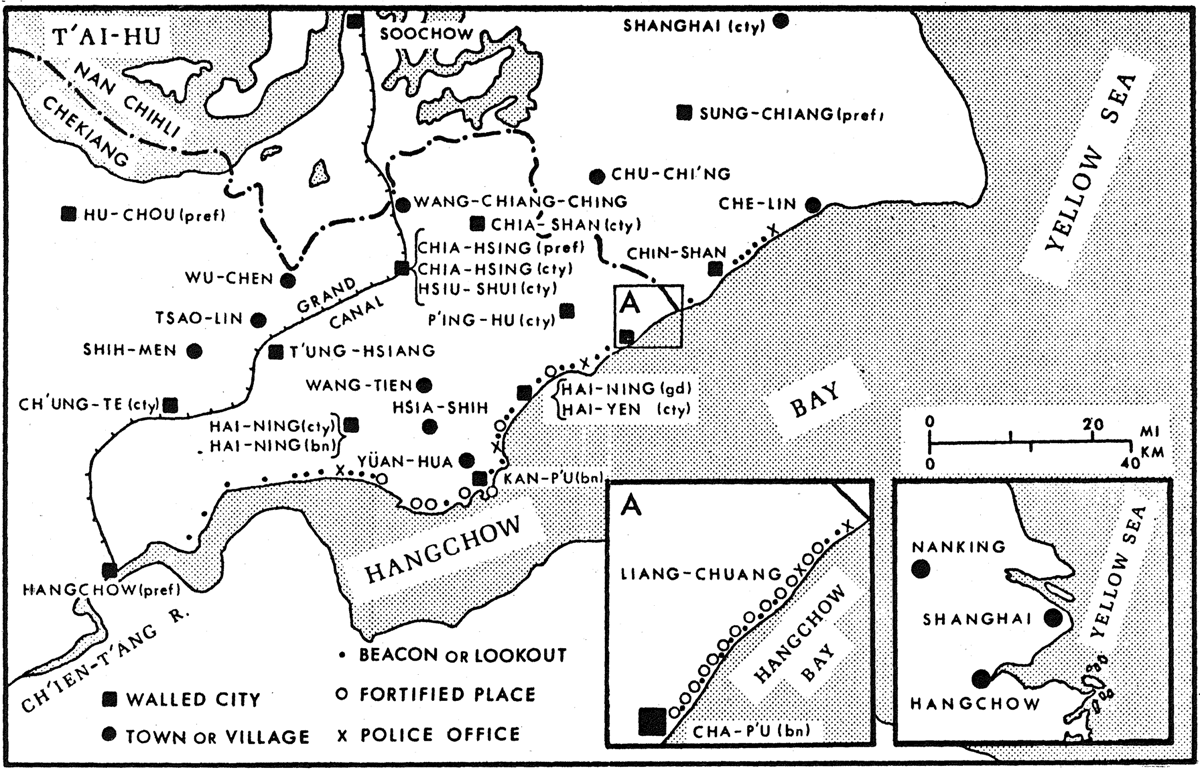

(1) There was the practical difficulty of trying to mount and maintain an adequate military defense along the entirety of Chinas long coastline.small forts, stockades, watchtowers, and beacon mounds along the whole coast from Korea to Annam. Moreover, they maintained naval fleets that were supposed to patrol the estuaries, coves, inlets, and offshore islands that abound south of the Yangtze River delta. Since Ming naval ships were superior to the vessels used by the marauders and were normally victorious in open sea battles, Ming authorities realized it was better to catch raiders at sea than to track them down once they were ashore. But there was little confidence that even a strong coastal fleet would in itself guarantee security. To catch marauders fleeing outward laden with booty was one thing; to anticipate and fend off those who were approaching was another. However well defended, the China coast was extraordinarily vulnerable to raiding attacks.

(2) Denying the marauders their bases and staging areas would have required Chinese conquest and control of the Liu-ch'iu Islands, Taiwan, and even part of Japan itself. Early in the Ming dynasty, when the famous eunuch admiral Cheng Ho led huge armadas across the Indian Ocean, the establishing of an overseas Chinese empire might have seemed possible. Both T'ai-tsu (13681398) and Ch'eng-tsu (14021424) at least tried to intimidate Japan with threats of invasion. In 1550 Altan Khan plundered into the very environs of Peking, and thereafter until 1570 there were recurring alarms in North China and extraordinary expenditures to shore up the northern defenses. The 1550's consequently were not a time for risky adventurings of any sort in other areas.

(3) Moreover, the coastal marauding was by no means solely a problem in foreign relations. The marauders were generally called Wo-k ' ou

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Two Studies on Ming History»

Look at similar books to Two Studies on Ming History. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Two Studies on Ming History and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.