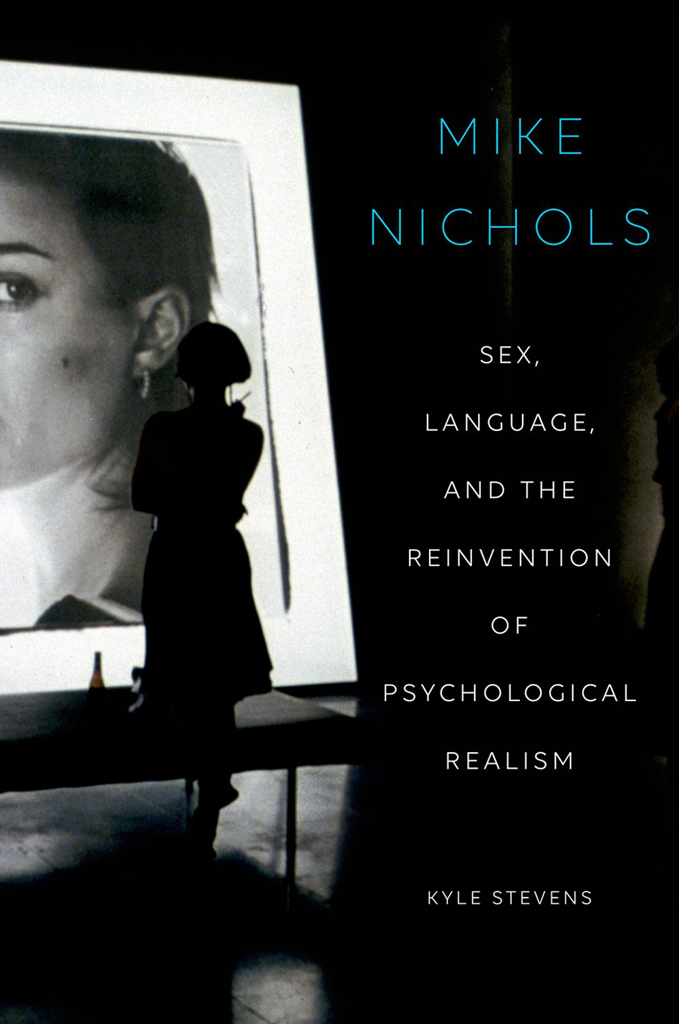

Mike Nichols

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stevens, Kyle.

Mike Nichols : sex, language, and the reinvention of psychological realism / Kyle Stevens.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199375806 (cloth) ISBN 9780199375813 (pbk.) eISBN 97801993758371.Nichols, MikeCriticism and interpretation.I.Title.

PN1998.3.N54S84 2015

791.430233092dc23

2015000087

For James, with whom I can be silent, and without whom I would be

{ CONTENTS }

One of the most surprising outcomes of the publishing process has been getting to know the indispensable editor Brendan ONeill. Even when not wearing his monocle, Brendans support, insight and acumen were vital from the beginning. The production team, including Stephen Bradley, Michael Durnin, and David Joseph, has also been fantastic.

This book began as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Pittsburgh, and I remain grateful to my advisor, Lucy Fischer, for giving me the freedom to pursue whatever avenues interested me while instructing me to walk before I try to run. I also thank my committee members, each of whom played an enormous role in shaping my approach to thinking about expressive culture. Colin MacCabe was the first faculty member at Pitt to take me seriously, and his enthusiasm and curiosity continue to inspire. He is, quite simply, the real deal. Marcia Landy was an intellectual beacon, with a frame of reference to which the rest of us can only aspire. Mark Lynn Anderson showed me that it is important to do academic work that is not just of academic interest, and David Shumway suggested that I write about performance in the first place. I am grateful to countless others during my time at Pitt, particularly Rick Warner, Peter Machamer, Randall Halle, Evgenia Mylonaki, Dan Chyutin, Ali Patterson, Devan Goldstein, Clint Bergeson, and Veronica Fitzpatrick. I doubt that I could have negotiated graduate school, or the field since, without Tanine Allison, my comrade in the trenches. Over the years since, I have received invaluable feedback and support on this work from a host of charitable people, most notably Victor Perkins, Christopher Beach, Thomas Doherty, John Bruns, Timothy Corrigan, and Ross Scarano.

I will always be full of thanks to my high school English teacher, Joseph Hill, who turned his classroom into the first safe intellectual space this frightened gay boy knew. He also made understanding Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf? seem like the most important thing in the world to do, an edict that I suppose I never quite shook. At the University of South Carolina, Susan Courtney saved my life and gave me reasons to study movies beyond my love of them, and at the same time.

The impossibly generous Daniel Morgan is profoundly more than a mentor to me, though I will stick to thanking him for that here. I thank him for his commentary and brilliant contributions on many of the pages that appear in this book, as well as for his knack of making me feel like I may be worth reading, a feeling that, as any writer knows, is hard to come by. There is no one to whom I would rather be indebted. Personal appreciation also goes to Shawn Francis, who intuitively understands the art of performance better than anyone. Above all, my gratitude goes to my champion and challenger, James Pearson, who improvises with me every day.

Mike Nichols

MARTHA: Truth and illusion, George. You dont know the difference?

GEORGE: No, but we must carry on as though we did.

This exchange is from Mike Nichols 1966 film Whos Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, an adaptation of Edward Albees play and his debut as a film director. It is the story of George and Martha, histrionic, witty spouses who live in a web of half-believed lies. As spectators, we are never certain whether their tales and accusations of past wrongdoings are true, false, or a mixture of both. Similarly, we are never sure whether the language games that they write and perform together throughout the storys time are manifestations of love or malice. This is to say that the very content of their consciousnessestheir motivations, desires, feelings, and so forthfluctuates. It flickers like the images before us. We cannot understand George and Martha, arguably the first couple of 1960s New Hollywood cinema and namesakes of Americas founding partners, by merely watching them or thinking about the objects of their actions. Since we remain uncertain of their intentions we are unable to describe exactly what it is that they do, and since characters are constituted by their actions, we are left to doubt who, and even what, these characters are. Hollywood doubted itself at this time, too. It was collapsing financially, fighting for an audience increasingly drawn to television, and finding its reputation as standard-bearer of cinematic style disputed by the sudden flow of international new wave cinemas into the country and around the world. What is more, America doubted its democratic self-identity, as the period of the biggest rights-led revolution in history forced it to confront its historical failures to fully recognize a person when it saw one. Inhabiting such doubt is, I show in the following pages, at the core of Nichols style, central to his five decades of remolding the Hollywood human.

Two years later, in 1968, that much-considered year, after Benjamin Braddocks recondite silences filled Nichols momentous The Graduate (1967), the New York Times attributed the enormous spike of students enrolled in film courses to the fact that, Mike Nichols and Jean-Luc ). Pairing these names is now surprising, as Nichols and Godard have probably not co-occupied a sentence since. Godard is one of the most discussed artists of the twentieth century; Nichols has not received any concentrated scholarly attention. Since cinema was at the center of expressive culture in the United States during this volatile time, it is hard to simply dismiss the newspaper of records reasoning. We might think that the names were intended as a juxtaposition, indicating the two standard directions in which movies are often thought aboutas art and as mass entertainmentand that these students may be divvied up into those seeking to make beauty (or beautiful political statements) and those seeking to make money. Or we might think that this coupling overestimated Nichols, failing to see that his style would not stand up to the test of time and that, unlike Godard, he would not continue on to radical aesthetic and political projects. However, to deflate the observation in these ways does justice neither to Nichols status at the time nor to the richness of his films.