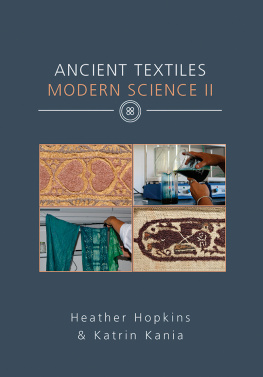

Ancient Textiles Modern Science II

ANCIENT TEXTILES SERIES 34

Ancient Textiles Modern Science II

Edited by

Heather Hopkins and Katrin Kania

Published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the author 2019

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-120-3

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-121-0 (epub)

eISBN: 978-1-78925-121-0

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-78925-122-7

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018960837

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

| UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

| Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

| Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 | Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

| Email: | Email: |

| www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

| Front cover: | Clockwise from top left: Fragment Inv.-Nr. T 9, Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe. BLM Karlsruhe, photo Th. Goldschmidt; Measuring of indigo liquid for vat dyeing. Photo Katrin Kania; Tunic RGZM Mainz, acc. no. O.22708, detail from the clavi. RGZM Mainz, photo V. Iserhardt; Hanging indigo-dyed textiles for oxidation. Photo Julie Strup. |

| Back cover: | Comparison between dyeing samples (see caption for full listings). |

Foreword

Michael Herdick

With pleasure I have the honour to write for the second time the foreword for a volume of selected papers from the European Textile Forum (ETF). In 2018, the textile archaeologists and craftsmen/women will meet for the seventh time at the Roman Germanic Central Museums (RGZM) Laboratory for Experimental Archaeology (LEA) in Mayen. Thereby it is possible to see the scholarly success of this presentation format that started as a private initiative. The annual programme provides possibilities to pursue personal research interests and scholarly exchange of ideas, as well as learning new craft techniques. The contributions in this anthology give an impression of the technical level and the will to make the findings of the international scientific community accessible to all.

Furthermore, the success of the ETF is a confirmation of the Laboratorys concept of providing a research infrastructure as part of the Leibniz Gemeinschaft, where external, scholarly-oriented persons can carry out their research. The lab itself is part of the Kompetenzbereich Experimentelle Archologie of the RGZM and was officially opened in 2012. The in-house areas of expertise include ceramic kiln technology and the raw material design of the Mayen pottery industry, as well as non-ferrous metallurgy and craftsmanship. For the colleagues and guests of LEA, there are two well-equipped workshops including potters wheels, smithy forges, electrical furnaces and diverse analytical equipment. Outside there are two custom-made shelters for long-term projects for reconstructed kilns and furnaces. In the case of workshops that run over several days, LEA has two sleeping quarters with a total of ten beds, as well as a separate seminar room at its disposal.

I can only hope that the ETF will continue to regularly report on the results of their work, with the same consciousness and attention to the quality that they have already shown to date.

Rmisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum

Leibniz-Research Institute for Archaeology

KB Experimental Archaeology and

Laboratory for Experimental Archaeology

Introduction

Heather Hopkins and Katrin Kania

We are delighted to introduce the second volume of proceedings for the European Textile Forum.

This book gives an insight into the wide variety of topics covered, discussed and explored during the week-long conference, which has grown into a yearly event. The European Textile Forum was originally developed around a large-scale spinning experiment which took place during the inaugural conference in 2009 in Eindhoven, Netherlands. After a few years of wandering, the ETF has found a steady home and a brilliant partner in the Laboratory for Experimental Archaeology in Mayen, where it was first hosted in 2012. Here, the generous support by the Rmisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum through LEA enables scholars, crafters and researchers from across Europe and around the world to get together and discuss, question and research historical textiles both in theory and in practice.

We hope that the articles published in this volume will be informative, helpful and inspiring to both those working on the theoretical and those working on the practical aspects of historical textile research. The ETF will continue to bring those parts together, hopefully for many years to come.

Chapter 1

On the terminology of non-woven textile structures and techniques, and why it matters

Ruth Gilbert

The terminology used with regard to looping, netting, knitting and other non-woven structures and techniques of textile manufacture is in general imprecise and can be confusing. In order to discuss these, including distinguishing clearly between them, it is essential to have a practical working vocabulary that describes the artefact and the way it is made. The aim of this paper is to provide a brief and referenced checklist for those concerned with the identification of artefacts. There are two major works on the subject of classification, one based on structure (Emery 1994) and one on technique (Seiler-Baldinger 1994); both give alternative terms from other authorities for comparison. The bibliography has been kept to a minimum, as the titles given will provide references for further reading on specific subjects.

The problem

Any one structure may be made in several ways, and one technique may produce many structures. The intention of this paper is to identify and name structures that are topologically identical. A topologist has been defined as a person who cannot tell a ring doughnut from a coffee mug, and in textiles this approach may require the lumping together of herring baskets and bobbin lace if they have the same structure. Specialists in basket making, lace making and other techniques have their own terminologies but there is a place for a description not dependent on the making process. The basic principle is: one structure or process, one term. Ambiguity is always a problem and although many of these are unfamiliar terms, words only become familiar through use. For clarity, non-English words are italicised in the text and preferred terms appear in bold.

It is often the case that a surviving artefact constitutes the only record of its production: what can be seen and described is the structure, and the technique . The alignment of threads in the structure produced by plaiting is shown at 45 to the edge of the band, therefore called plain oblique interlace , but what bobbin lace makers call cloth stitch is a one-set-of-elements plaited plain interlace made as though woven, with thread alignment parallel to the edges of the work. Without surviving selvedges the orientation of a piece cannot be known. As a comment on the whole process of naming, no-one would ask a bobbin lace maker to call their structure one-set-of-elements plain rectilinear interlace, because for their purpose cloth stitch is adequate, but other techniques must be borne in mind as possible before assuming that a scrap, or the imprint of a scrap on a pot or metal artefact, was made by weaving. For the purposes of this paper weaving is a two-sets-of-elements technique with a fixed warp under tension and a mechanical means of separating the warp into sheds. Any structure that can be made by weaving can also be made in some other way; loom weaving is a late addition to the textile crafts, favoured for speed in spite of the limitation of possibilities.