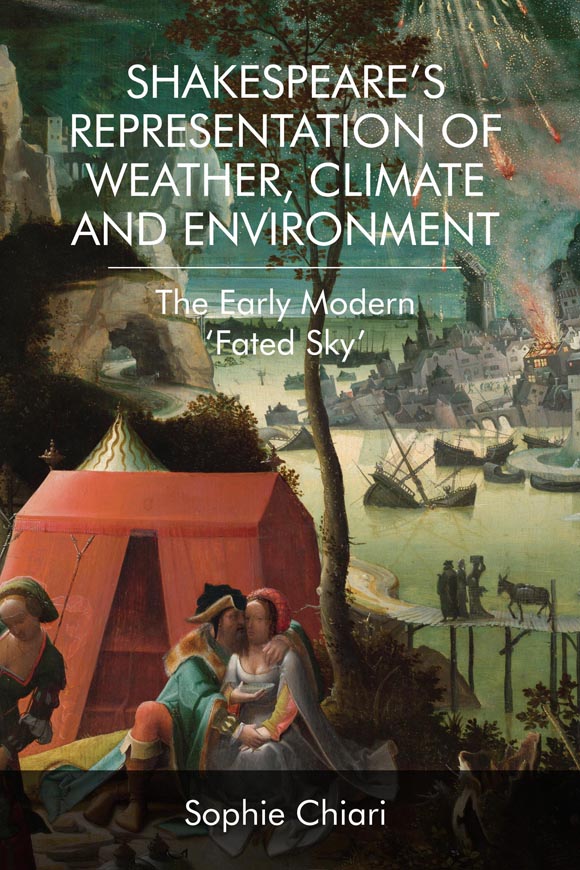

Shakespeares Representation of Weather, Climate and Environment

[...] never till tonight, never till now,

Did I go through a tempest dropping fire.

(Julius Caesar, 1.3.910)

Shakespeares Representation of Weather, Climate and Environment

The Early Modern Fated Sky

Sophie Chiari

EDINBURGH

University Press

Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com

Sophie Chiari, 2019

Edinburgh University Press Ltd

The Tun Holyrood Road

12(2f) Jacksons Entry

Edinburgh EH8 8PJ

Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by

IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and

printed and bound in Great Britain.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 4744 4252 7 (hardback)

ISBN 978 1 4744 4254 1 (webready PDF)

ISBN 978 1 4744 4255 8 (epub)

The right of Sophie Chiari to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498).

Published with the support of Institut dHistoire des Representations et des Idees dans les Modernites (IHRIM, UMR 5317), under the aegis of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), ENS de Lyon, Universit Lumire-Lyon 2, Universit Jean-Moulin-Lyon 3, Universit Jean-Monnet-Saint-Etienne, and Universit Clermont Auvergne.

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

The writing of this book would not have been possible without the research conditions that I have enjoyed over the past three years. My research team, IHRIM (Institut dHistoire des Reprsentations et des Ides dans les Modernits, UMR 5317, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), has been a source of intellectual stimulation and has allowed me to travel both in France and abroad for my research. Olivier Bara and Marina Mestre Zaragoz have generously given me the freedom I needed for my work and they have supported me all along. My colleagues at Universit Clermont Auvergne (UCA, France) have also provided me with a friendly and welcoming environment which has helped to make things much easier for me. In addition, I have often tested my ideas in my Master and Agrgation classes and I am grateful to my students for their patient attention and their responsiveness.

While I am clearly indebted to ecocriticism at large and to the numerous studies that aim at reconciling early modern literature with early modern science, my collaboration with learned and friendly colleagues such as Mickal Popelard and John Mucciolo has been particularly fruitful and important to me. Colleagues and friends read portions of the book along the way. Edward Paleit and Jean-Marie Maguin kindly agreed to look at a first draft of this text while Sophie Lemercier-Goddard and Tiffany Jo Werth each commented on separate chapters, and I am deeply indebted to the four of them for their thoughtful remarks. I also warmly thank Jonathan Pollock for his suggestions and clarifications.

I would also like to express my personal gratitude to Roger Chartier and Stephen Greenblatt for their encouragement and for the time they were kind enough to give me in spite of their frantic schedules. My thanks also go to Dympna Callaghan, Richard Dutton, Frank Lestringant and Carla Mazzio for their unfailing support and their immediate adherence to the overall project.

On top of that, I have been fortunate, over the past five years, to organise and participate in lectures, conferences and seminars directly or indirectly related to the subject of this study. Stimulating exchanges with several participants have helped me to go ahead with my project in many more ways than I can say. The various papers I had the opportunity to give in conferences or seminars on weather and climate in early modern England were the starting points of some of the chapters of this book. In particular, the ninth Congress of the Shakespeare Society of Southern Africa in Grahamstown, which offered me the opportunity to present a climatic reading of A Midsummer Nights Dream, Romeo and Juliet and King Lear, proved a decisive moment that gave me the necessary impetus and confidence to turn a budding project into a full-length monograph.

I am also grateful to the curators and librarians for the help and assistance they have provided me with at Bibliothque Nationale de France, the British Library, the Huntington Library, the Bodleian Library and Cornell University Library. My thanks more particularly go to Anne Chesher, Deputy Librarian at Magdalen College, who helped me locate an engraving in John Hardings copy of the Bible, and to Luise Poulton, Managing Curator at J. Willard Marriott Library, who drew my attention to the 1551 Paris edition of Peter Apians Cosmographia.

The two anonymous readers of the first draft of this book are finally to be warmly thanked since their comments and advice have certainly helped me improve my work and flesh it out with additional details. Last but not least, I warmly thank Franois Laroque for his kind support and understanding while I was writing this book.

Textual Note

Original spelling has been retained whenever I quote from early modern editions but I have systematically replaced long ss by short modern ones and I have expanded contractions such as tildes in order to make these texts more accessible to the readers.

Unless otherwise stated, the following editions of Shakespeares plays have been used for the seven chapters of this book:

A Midsummer Nights Dream, ed. Peter Holland, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Romeo and Juliet, ed. Jill L. Levenson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

As You Like It, ed. Michael Hattaway, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, The New Cambridge Shakespeare, (2000) 2009.

Othello, ed. Michael Neill, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

King Lear, ed. Ren Weis, A Parallel Text Edition, 2nd edn, London: Routledge, (1993) 2010.

Anthony and Cleopatra, ed. Michael Neill, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

The Tempest, ed. Stephen Orgel, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

References to Shakespeares other works are to The Complete Works, ed. Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett and William Montgomery, 2nd edn, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005.

Introduction

And as it was in the dayes of Noe [...]

[...] the flood came, and destroyed them all.

Like wise also, as it was in the dayes of Lot [...]

[...] it rained fyre and brimstone from heauen, and destroyed them.

Climate generates fears and superstitions generally assuaged by religious rituals and representations. In England, the Reformation tried to eradicate the beliefs of the old religion but, as far as climate and weather are concerned, no really satisfactory results were achieved. The sky remained ominous and often threatening while astrological attempts to read ones destiny in the stars (well before William Herschels observations) long continued to flourish. At any rate, in the Geneva Bible, Shakespeares contemporaries could find plenty of stories telling of the erratic weather caused by Gods wrath and were used to reading the changes in the English firmament in the light of the Scriptures. Most of them still thought that, because of mens ingrained tendency to sin, the rain poured down from the heavens, threatening to engulf the peasants yearly harvests, if not humanity at large, and flashes of lightning cracked in angry skies, punishing human hubris.

Next page