Alexander Wolfheze

Alba Rosa

Ten Traditionalist Essays

about the Crisis in the Modern West

Arktos

London 2019

Copyright 2019 by Arktos Media Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means (whether electronic or mechanical), including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Arktos.com | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram | Gab.ai

ISBN

978-1-912975-09-9 (Paperback)

978-1-912975-10-5 (Ebook)

Editing, Cover & Layout

John Bruce Leonard

List of Illustrations

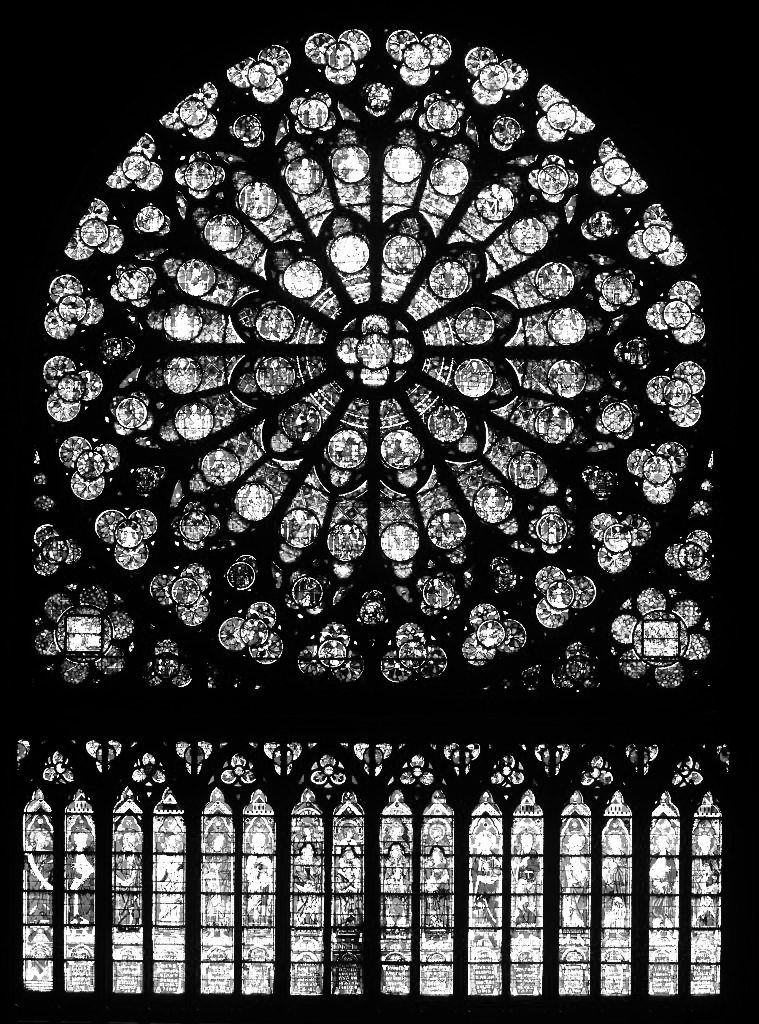

1. Rose du Midi, South Rose Window, Notre Dame de Paris

2. Christs Descent into Hell, student of Hieronymus Bosch

3. Arcite and Pacamon admire Emilia, unknown master

4. The Fighting Temeraire Tugged to Her Last Berth to be Broken Up, Joseph Mallord William Turner

5. Le silence. Les camps de reconcentration au Transvaal, Jean Veber

6. The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, illustration from a Fl-Nmeh

7. Offrande la Vierge, Offering to the Virgin, Simon Saint-Jean

Take my shoes off

And throw them in the lake

And Ill be

Two steps on the water

Kate Bush, Hounds of Love

Dedicated to our people:

ceci tuera cela

1. Before the High Altar of History

Rose du Midi, South Rose Window, Notre Dame de Paris (ca. 125060 an offering by King Saint Louis). The central mdaillon shows Christ Triumphant, i.e. Christ as depicted in the Book of Revelation, with the Sword of Truth coming from His mouth; He is surrounded by the saints and martyrs that bore witness to Him on Earth. The vision of the Rose du Midi will have been one of the last earthly sights of Dominique Venner as he was standing before the High Altar.

Preface

Lheure viendra cependant o, dans un monde organis pour le dsespoir,

prcher lesprance quivaudra tout juste

jeter un charbon enflamm au milieu dun baril de poudre .

[Yet the hour will come when, in a world organized for despair, preaching hope will be the same as throwing a glowing coal in a keg of gunpowder.]

Georges Bernanos, Monsieur Ouine

The High Altar of History

M any years have passed since the author, in his second high school term of German language instruction, first saw the writings of Die Weisse Rose a long time ago, in the long-drowned world of pre-digital learning and unpractical bookish wisdom. Facing the sweetly romantic theme of the rose of purity, the boys in class resigned themselves to a long and boring sessionthe girls eagerly grabbed their poetry albums. At that time, forty years after the Second World War, German language education was still somewhat tainted in the Netherlandsa fact hardly counterbalanced by the latent but pervasive anti-Semitism still experienced by those pupils suspected to be of Jewish stock. On this occasion, however, the teacher managed to gain the full attention and appreciation of his reluctant class. It appeared that the rosy theme concerned a small group of German stu dentsnot much older than the pupils who were reading their typed es says four decades laterwho had actually paid with their lives for a few sheets of brave, but unwelcome prose and verse. If it was the guillotine that put a full stop behind their words, perhaps their words actually deserved some attention. Of course, after the end-of-term exam, not much would be remembered of what was learnt that day, except the naked name nomina nuda tenemus and the vague impression of a wrongly scripted David-and-Goliath tale. The theme of the history of Die Weisse Rose the almighty giant of the totalita rian dictatorship that crops a few loud boys and girls at the neck for the sake of the politically correct remainder of a sleeping nationwas simply too far remote from the actual realities of the free and democratic Netherlands of the mid-80s. At that time, totalitarian repression and brutal dictatorship were only found in remote, primitive regions of the worldand behind the Iron Curtain. There, the Bolshevik world still brought forth brave warriors of the pen, worthy successors to Die Weisse Rose : samizdat heroes such as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn with his Odin den Ivana Denisowitsa and Vaclav Havel with his Moc bezmocnych .

Who could have guessed, at that time, that the theme of Die Weisse Rose would one day gain concrete relevance, a relevance extending beyond mere historical curiosity, for the proudly free and exemplary democratic Dutch nationor for any progressive Western nation? Who could have guessed that one day, totalitarian ideology and dictatorial politics would not be brought into the Netherlands by foreign occupiersas the Germans did during the Second World Warbut be brought forth by the Dutch soil itself? What about the assumption that German National Socialism had been a unique aberration in Western historyan unfortunate, but entirely plausible Sonderfall from the point of view of historical-materialist theory? What about the assumption that Russian Bolshevism and its imperialist metastases in Eastern Europe and overseas were equally unfortunate, but essentially temporary phenomena, owed to underdevelopmentand destined to disappear with material progress and advancing enlightenment? And were these historical-materialist assumptions not soon proven true by subsequent history: by the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Soviet Union and Apartheidand by the rise of the EU, the euro and the World Wide Web? The events and rhetoric of the early nineties seemed to be the ultimate confirmation of historical-materialist teleology: with George Bush launching the New World Order and Francis Fukuyama announcing the End of History, the post-historical, Postmodern Era had begun.

How could the sporadic incidents of Black Hawk Down, 9/11 and Abu Ghraib be anything more than easily removable dust specks on the stainless record of the New World Orderinsignificant bumps on the highway to a utopian Brave New World of global peace, freedom and democracy? How could any critic of this glorious vision be more than an angry white man and a pitifully unstable person, fully deserving his sad fate? From this perspective, it is entirely plausible that only twelve years after the murder of patriotic Dutch prime ministerial candidate Pim Fortuyn (6 May 2002), his assassin was again a free man. The court decided that the murderer, obligingly characterized as a lone wolf, was simply an overly conscientious Social Justice Warrior. The victim, despite his posthumous election as second greatest Dutchman in history, had been widely portrayed in the media as a danger to society. From this perspective, it becomes also entirely plausible that the dramatic suicide of cultural critic Dominique Venner, in front of the High Altar of the Notre Dame de Paris (21 May 2013), should have been followed within twenty-four hours by a half-nude act of mockery by a Social Justice Warrior member of the militant feminist action group Femen.

But what if there actually existed entirely different perspectives on such events? Was it not actually true that this sextremist Femen activist, this blasphemous empress of dystopian anti-Tradition, stood without clothes? Was it not actually true that she was shamelessly profaning hallowed groundand that the word hell was written on her naked belly? And what about the ancient words of the Bible: Babylon the Great, Mother of Harlots and Abominations of the Earth, drunken with the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs ? Is it possible that these words were somehow applicable not only to that one Anti-Notre Dame of Femen, but also to the whole New World Order that she represented? And, if so, then how had it been possible for such a horrible new regime to rise up in the heart of Western civilization, without being properly noticed, without being bravely denounced and without being seriously resisted? Had similar questions not plagued the students of Die Weisse Rose , and had they not reached terrible conclusions? They had been born too late and their questions had been asked too late as wellten years after the National Socialist Machtergreifung . But the brave sacrifice of Die Weisse Rose will not have been in vain if later-born youngsters can understand it correctlyif they learn to act punctually whenever they learn about a new totalitarian Machtergreifung .

Next page