Table of Contents

This book is dedicated to those who live and work with garbage

Acknowledgments

I began investigating the subject of garbage by making a documentary film in 2002, also titled Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage. Once the film was complete, I realized that there was much more to say on the subject: thus this book. The people who contributed to the book overlap with those who helped on the film.

The insights of the interviewees in the documentary have been greatly influential: Tim Krupnick from the Batcave, Dave Williamson of Berkeleys Ecology Center, and Charles Homes all helped me more fully understand the issues and contradictions of recycling; Mary Lou VanDeventer offered an astute take on garbage and made key reading recommendations that set me on the right course; John Marshall continued to talk with me about labor and garbage well after the film was complete, and raised key points during the writing of the book; and, with his keen analysis, Richard Walker helped me grasp the complex meanings of garbage in a market economy.

In New York, thanks to the Brecht Forum, and to Cathryn Swan and Christina Salvi of Recycle This! for screening the movie and providing a context to discuss my ideas with a diverse range of people. Thanks as well to Robin Nagle for sharing some of her contacts at the New York Department of Sanitation and the Newark, New Jersey, incinerator.

I am indebted to David Harvey, who let me sit in on many of his classes while I was writing this book. His superb discussion of political economy deeply informs my analysis. Thanks as well to Christian Parenti for his intellectual comradeship, help on the film, introduction to The New Press, and early encouragement to write this book. Christians observations and thoughts were crucial to this undertaking; it was with him that I most thoroughly discussed and worked through my ideas about garbage and how to write about it.

I am grateful to Colin Robinson for his overall support, engagement with the project, and absolutely crucial feedback on the initial manuscript. Liza Featherstones enthusiasm for the movie and then the book has been invaluable. Once the writing was under way, she offered an abundance of useful comments, initially as a fellow author, and later as my editorthe book benefited greatly from her input. David Morris generously read an early version of the manuscript and made suggestions that proved extremely helpful. Praise to Steven Hiatt and Elinor Pravda for their careful, top-notch work on the production of the book. And much appreciation to Elizabeth Seidlin-Bernstein and The New Press staff and interns for all their behind-the-scenes work.

Thanks to librarians, who keep information free and accessible, and thanks to all the friends who sent articles and recommended books to read. For their help in providing photographs for the book, I am grateful to Michael Lorenzini at the New York City Municipal Archive; Marguerite Lavin at the Museum of the City of New York; and James Martin, a retired public works engineer from Fresno, California. Thanks also to the artist Peter Garfield for his excellent portrait of garbage. Todd Chandlers stellar computer skills made organizing the photographs for publication a breeze. Thanks as well to Sam Cullman for additional technical assistance.

Much gratitude, for a variety of reasons, to Rachael Rakes, Scott Fleming, Penny Lewis, Emily De Voti, Tedd Hamm, Christopher D. Cook, Theresa Kimm, Thomas Green, Braden King, Susan Parenti, Josh W. Mason, Doug Henwood, Rick Prelinger, Neil Smith, Nancy Newhauser, and the Blue Mountain Center, where I worked out my initial ideas for the book. And warm thanks to my cousin Charlie Rogers, and my sister Holli Rogers, both of whom read parts of the book in a much rougher form and offered unswerving encouragement along the way.

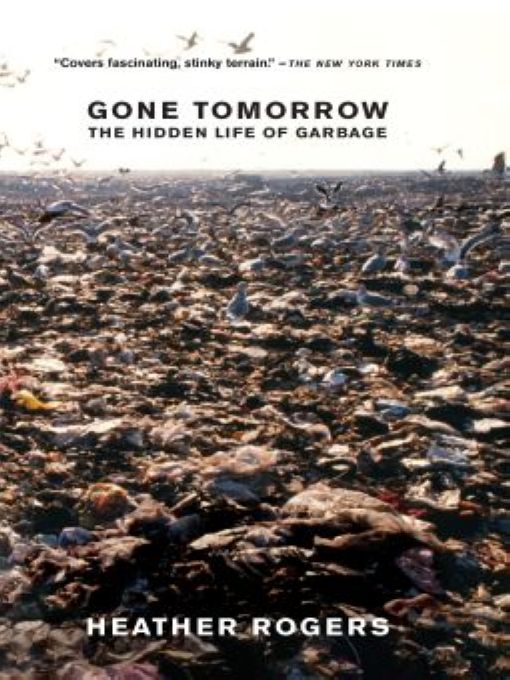

Partial view of Fresh Kills landfill. (Courtesy of the New York City Department of Sanitation, Bureau of Waste Disposal)

Introduction

The Conquest of Garbage

A society in which consumption has to be artificially stimulated in order to keep production going is a society founded on trash and waste, and such a society is a house built upon sand.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS Why Work? 1942

From outer space several human-made objects are visible on earth: the Great Wall of China, the pyramids, and, on the southwestern tip of New York City, another monument to civilization, Fresh Kills Landfill. Briefly a depository for the gory debris of 9/11, this colossal waste heap looks rather like a misplaced Western butte. Its fifty-three years worth of refuse are mostly covered by graded dirt and grasses, and not far off one can see what looks like a functioning estuary. On a bad day the methane stench of consumption past wafts up from the guts of the hill, and when storms hit, toxic leachate flows into the surrounding surface and groundwater. If garbage were a nation, this would be its capital. Its an astounding place, but apart from its size, not so unusual.

In 2003 Americans threw out almost 500 billion pounds of paper, glass, plastic, wood, food, metal, clothing, dead electronics and other refuse.

Eat a take-out meal, buy a pair of shoes, read a newspaper, and youre soon faced with a bewildering amount of trash. And forget trying to fix a broken toaster, malfunctioning cell phone or frozen VCRnowadays its less expensive to toss the old one and purchase a brand-new replacement. Many people feel guilty about their waste and helpless over how to avoid it. This angst intensifies if our discards arent promptly hauled away. Consider this tortured passage from a Chicago journalist writing during a 2003 garbage strike:

I want to improve the environment. I do. But looking at an extra weeks worth of Lucky Charms With New Larger Marshmallows boxes and Conair packaging and empty water bottles and ripped-up Instyle magazines and dried-out nail polish in Bus Stop Crimson and Gap bags.... I wonder if maybe Im not doing my part.

The mounting trash is a constant reminder of how much we spend. How much we consume. How much we waste.

Wont someone please come take it away?

Disruptions in the channeling of trash out of our immediate lives are infrequent; most often the rubbish gets collected on time. But even when the system works well, a nagging feeling can linger: Where does it all go? The opening lines of the popular 1989 film Sex, Lies, and Videotape bring these repressed anxieties to the surface. Andie MacDowells character confesses to her therapist: Garbage. All Ive been thinking about all week is garbage.... I mean, weve got so much of it. You know, I mean, we have to run out of places to put this stuff, eventually. Many people today feel at least a little uneasy about the profusion of garbage that our society produces. But while its fate most often lies hidden, trash remains a distressing element of daily life, linked to much larger questions that never really go away.

Garbage is the text in which abundance is overwritten by decay and filth: natural substances rot next to art images on discarded plastic packaging; objects of superb designthe spent lightbulb or batterylie among sanitary napkins and rancid meat scraps. Rubbish is also a border separating the clean and useful from the unclean and dangerous. And trash is the visible interface between everyday life and the deep, often abstract horrors of ecological crisis. Through waste we can read the logic of industrial societys relationship to nature and human labor. Here it is, all at once, all mixed together: work, nature, land, production, consumption, the past and the future. And in garbage we find material proof that there is no plan for stewarding the earth, that resources are not being conserved, that waste and destruction are the necessary analogues of consumer society.