Chapter One

When we were in school, our English teachers gave us explicit details about how to write a five-paragraph theme: introduction, thesis sentence, point one, point two, point three, and conclusion. But when it came to writing creative fiction, odds are that your teacher said, Just tell me a story.

No wonder so many storytellers falter when it comes to creating their own stories! We move from the ordered world of nonfiction into a world that can appear to be a whirling ebb and flow of ideas. To the uninitiated, it can feel like a riptide and its hard to make any headway.

But creative fiction does have a structure, and its been around for ages. From Joseph Campbells study of the heros journey to Syd Fields exploration of screenwriting structure, others have found and analyzed plot structure with sometimes confusing terms.

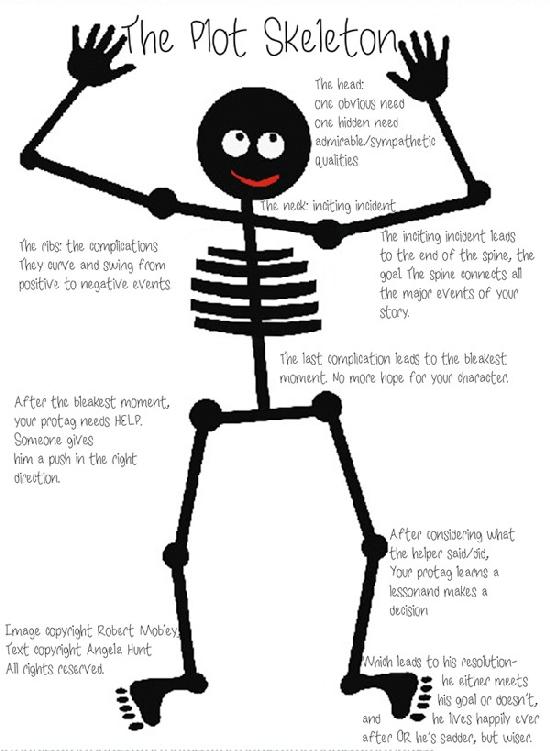

A few years ago, I was hired to teach writing to homeschooled students from third through twelfth grades. I wanted to teach them to plot, so I searched for a method that was easy to understand and yet completely sound. After studying several plotting techniques and boiling them down to their basic elements, I developed what I call the plot skeleton. It combines the spontaneity of seat of the pants writing with the discipline of an outline. It requires a writer to know where hes going, but it leaves room for the joy of discovery on the journey.

Best of all, the method is visual. You dont have to have a lick of artistic ability, but if you can draw a round head, some ribs, and some skinny leg bones, you can draw a skeleton that will guide you through the plotting process.

A Bare Bones Outline

Imagine, if you will, that you and I are sitting in a room with one hundred other writers. If you were to ask each person to describe their plotting process, youd probably get a hundred different answers. Writers methods vary according to their personalities and we are all different. Mentally. Emotionally. Physically.

If, however, those one hundred writers were to pass behind an x-ray machine, youd discover that except for slight gender differences we all possess remarkably similar skeletons. Unless someone has been unfortunate enough to experience some kind of deformity, beneath our disguising skin, hair, and clothing, our skeletons would be nearly indistinguishable.

In the same way, though writers vary in their methods, good stories are composed of remarkably similar skeletons. Stories with good bones can be found in picture books and movies, plays and films. The only difference in most stories is length, and length is usually determined by the breadth of the workhow many subplots are involved, and how many complications the protagonist must face.

Many fine writers carefully outline their plots before they begin the first chapter while others describe themselves as seat of the pants plotters. But when the story is finished, a seat-of-the-pants novel will usually contain the same elements as a carefully plotted book. Why? Because whether you plan from the beginning or work through intuition, novels need structure to support the story.

When I sit down to plan a new book, the first thing I do is sketch my smiling little skeleton.

To illustrate the plot skeleton in this article, Im going to refer frequently to The Wizard of Oz, The Sound of Music, and a lovely foreign film you may have never seen, Mostly Martha.

One more thing: my lessons are never intended to be a set of rules that must never be broken. What I want to offer are guides to the art of writing. Take what you learn here, visualize it, practice it, and then use it in your own way to create your story.

The Skull

The skull represents the main character, the protagonist. A lot of beginning novelists have a hard time deciding who the main character is, so settle that question right away. Even in an ensemble cast, one character should be more predominant than the others. Your reader wants to place himself into your story world, and its helpful if you can give him a sympathetic character with whom he or she can relate. Ask yourself, Whose story is this? That is your protagonist.

At the very beginning of your story, this main character should be dealing with two situations, which I represent in the skeleton by two yawning eye sockets: one obvious problem, one hidden need.

Heres a tip: hidden needs, which usually involve basic human emotions, are usually resolved or met by the end of the story. They are at the center of the protagonists inner journey, or character change, while the outer journey is concerned with the main events of the plot. Hidden needs often arise from wounds in a characters past.

Consider The Wizard of Oz. At the beginning of the film, Dorothy needs to save her dog from Miss Gulch, who has arrived at the farm to take Toto because he bit Miss Gulchs scrawny lega straightforward and obvious problem. Dorothys hidden need is depicted but not directly emphasized when she stands by the pigpen and sings Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Do children live with Uncle Henry and Aunt Em if all is fine with Mom and Dad? No. Though we are not told what happened to Dorothys parents, its clear that something has splintered her family and Dorothys unhappy about the result. Her hidden need, the object of her inner journey, is to accept her new home.

The Sound of Music opens with young Maria dancing and singing in a mountain meadow. As we watch, we learn that this free spirited woman loves music and life, and that she has voluntarily entered a conventto serve God and others, we may safely assume. But the girl, dear as she is, is simply not fitting in. The other nuns love her, but she distracts them from their prayers and she cant seem to keep her lively spirit from showing up at times when she should be quiet and contemplative. The nuns sing, How Do you Solve A Problem Like Maria? Like the song says, molding Maria to convent life is like holding a moonbeam in your handimpossible. A fairly obvious problem.