Contents

Guide

Page List

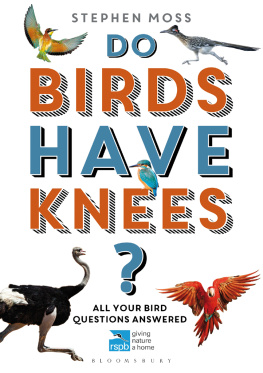

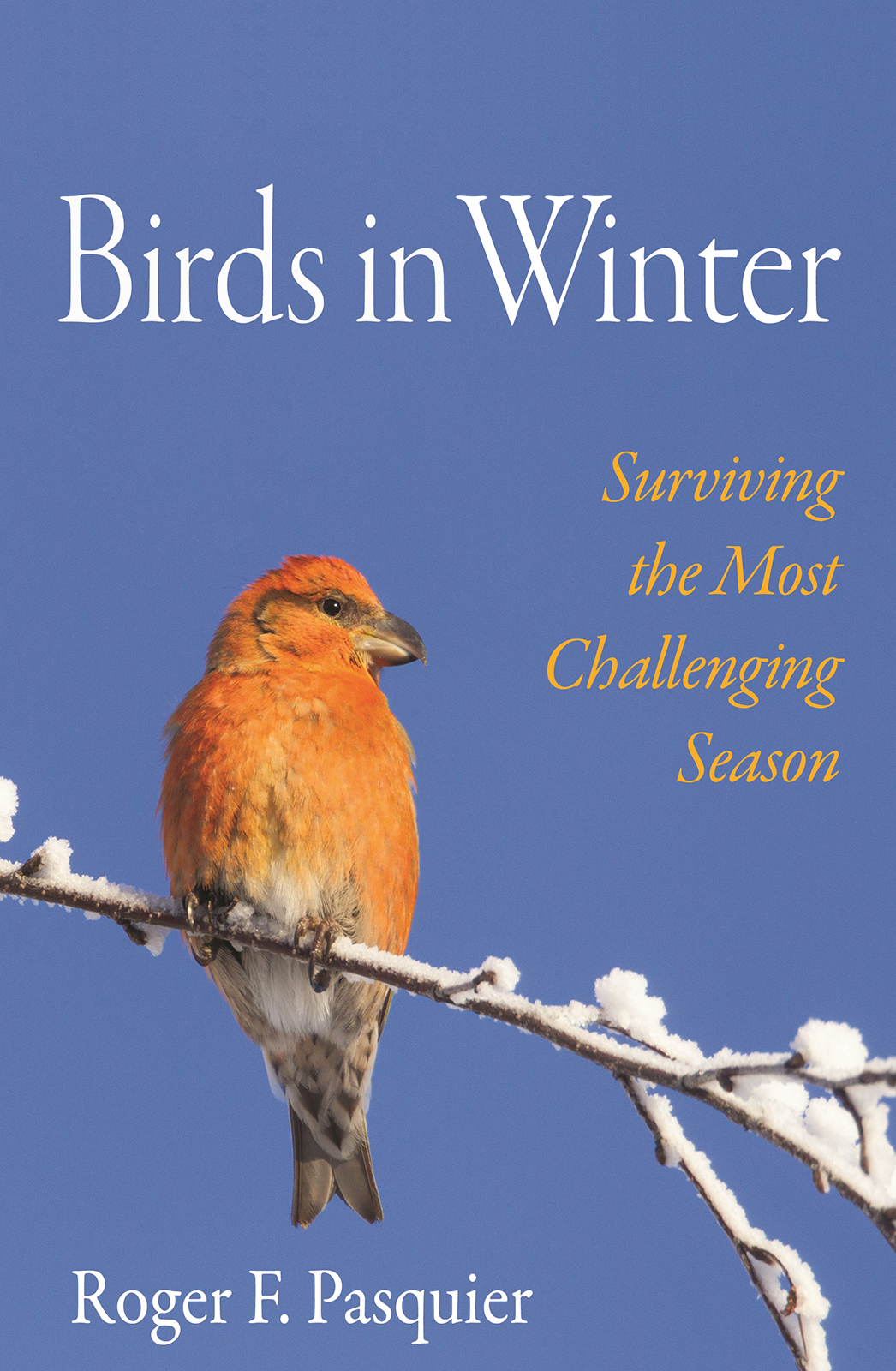

Birds in Winter

Surviving the Most Challenging Season

Roger F. Pasquier

Illustrations by Margaret La Farge

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018958180

ISBN 978-069-117855-4

eISBN 978-069-119543-8 (ebook)

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Robert Kirk and Kristin Zodrow

Production Editorial: Ellen Foos

Text Design: D & N Publishing, Wiltshire, UK

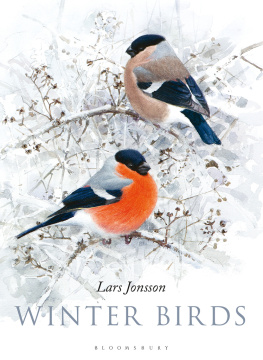

Jacket Design: Lorraine Doneker

Jacket image: Markus Varesvuo/Agami Picture Library

Production: Steven Sears

Publicity: Matthew Taylor and Julia Hall

Copyeditor: Laurel Anderton

For

Phoebe Goodhue Milliken

CONTENTS

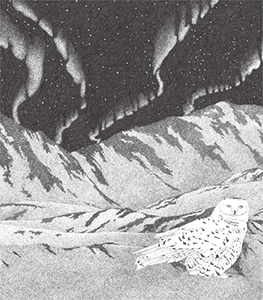

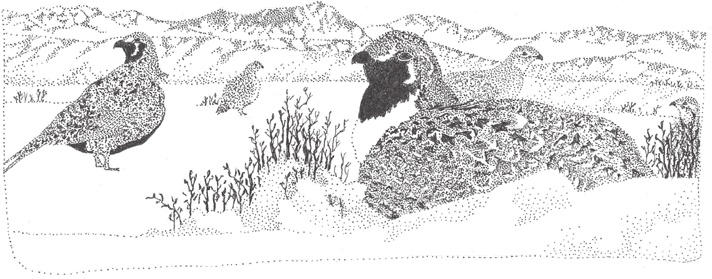

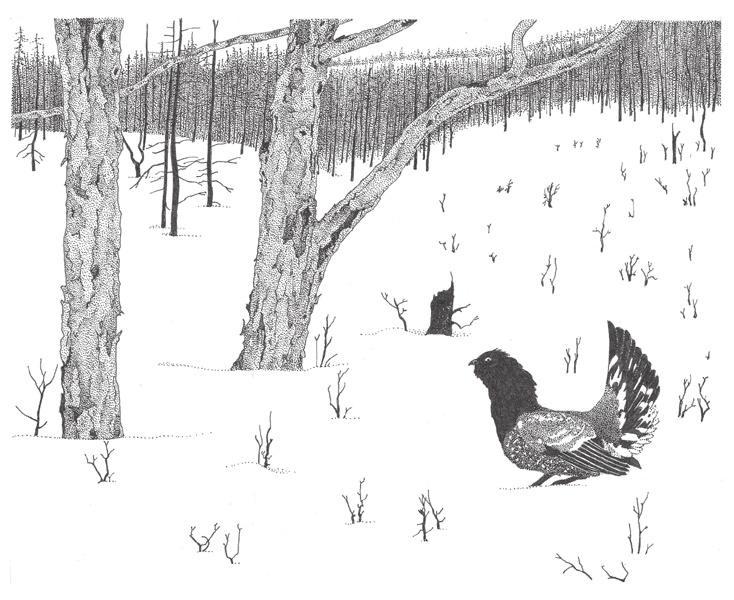

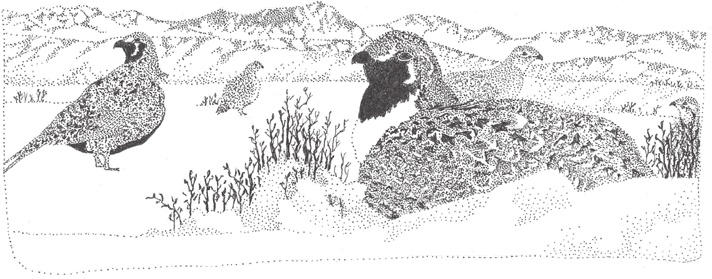

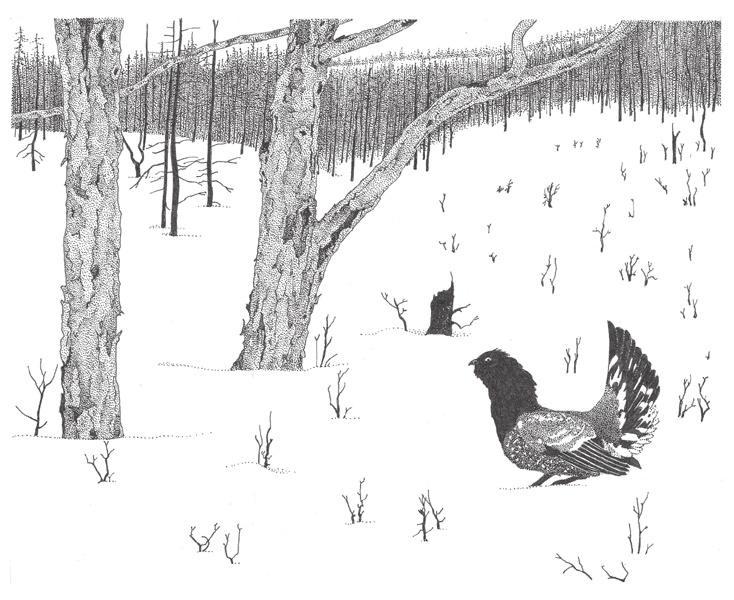

Male Black-billed Capercaillies in Siberia eat larch twigs through the winter, picking whatever is above the snow. This increases the number of shoots that will grow from the stem the next spring, providing food the following winter.

INTRODUCTION

I N 1976, WHEN I was writing Watching Birds: An Introduction to Ornithology, I had an abundance of books and papers in scientific journals to draw from as I described the breeding behavior and migrations of birds. Conspicuously missing, however, was a comparable level of information on the remaining portion of the annual cyclewinterwhich to me seemed no less interesting, and no less vital to understanding the lives of birds. I believe the chapter on winter I wrote for Watching Birds was then the first unified, albeit modest, account of the ecology and behavior of how both permanent residents and migrants deal with that season. I was sure there was much more to be researched and brought together, and I immediately proposed the idea to my editor as my next book. Too narrow a topic! was the response then, as well as later in a succession of intervals, each of about fifteen years, when I proposed it again to subsequent editors.

Finally, in 2015, after completing Painting Central Park, another book I had long wanted to write, I decided to take the plunge, research the topic of birds in winter in all its aspects, and determine for myself whether there was a book in it. Over those nearly 40 intervening years, winter had also come to interest a new generation of ornithologists. The Smithsonian Institutions 1977 and 1989 symposia on the ecology and conservation of migrant birds in the Neotropics, for example, brought together tremendous amounts of essential information, inspired even more research, and produced publications that are still primary references. The years around the turn of this century saw expanded interest in austral migration and winter in Australia and South Americawhere, in fact, W. H. Hudson had vividly depicted it in Far Away and Long Ago (1918) based on his boyhood memories of Argentina in the 1870s.

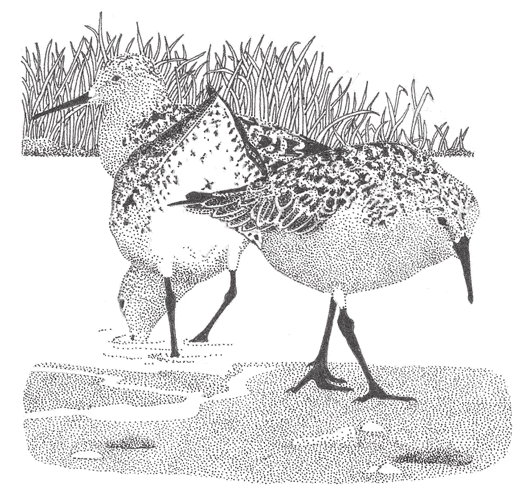

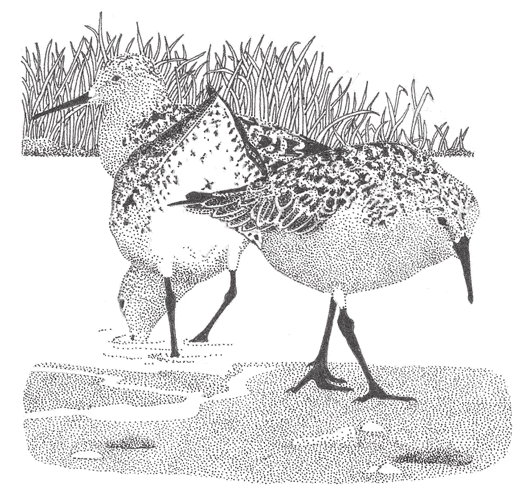

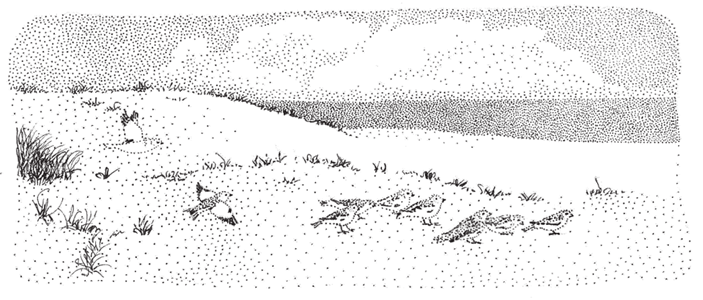

Over these decades, ornithologists in Finland and Scandinavia were publishing a steady stream of papers describing the social and ecological winter dynamics of boreal forest birds, while from Britain and the Netherlands were coming accounts of how shorebirds spend that season in northerly latitudes, permitting useful comparisons with the North American and Eurasian shorebirds that winter far south of the equator. Similarly, in North America intensive long-term studies of chickadees and juncos have revealed the complexities of their winter lives. (Sadly, there is still very little information about the birds wintering in Southeast Asia, where forests are being cut at an alarming rate, or from much of Africa, where more frequent and intense droughts are transforming the landscape.) The recent rapid advances in satellite tracking technology and stable isotope analysis have enabled scientists to follow individual birds day by day and practically meal by meal all through the winter when these birds are continents and oceans away. And today the growing concern about conservation, especially the loss of wintering habitat, and the impacts of climate change have added new perspectives and new urgency to understanding the entire annual cycle of birds.

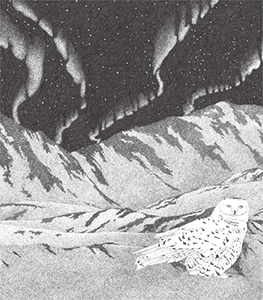

So, in 2015 I was glad to return to a seat at the same table in the library of the Department of Ornithology in the American Museum of Natural History where I had written Watching Birds. The perfect place to research and write. Ive never had more fun! When discussing the feathered toes of the Snowy Owl, the differences in bill lengths of North American and Caribbean kingbirds and vireos, or a species like the Tibetan Ground Tit that I did not know at all, I could look at the specimens. It was hard to say basta! to research when every newest issue of one of more than 20 ornithological, behavioral, ecological, and conservation journals I was following might have something amazing and irresistible to include. I drew the line at the last of the mid-2018 publicationsand hope I will not soon regret it.

Of course, when I described my project, some people thought my topic was simply the familiar birds of northern latitudes that stay where it is cold. But no, winter is a global phenomenon, and it influences birds all over the world, including many of those that never leave the tropics but must share their habitat during parts of the year with birds from the Northern or Southern Hemisphere, or from both. We routinely say Blackburnian Warblers winter in Colombia and White Storks winter in Africa, so there seemed every reason to follow them there to learn the challenges of that season and how the birds fit into those ecosystems. (I have kept the discussion of how migrants reach their winter destinations to a minimum, since today there are more books on migration, dazzling in their comprehensiveness, than ever before.) And, since life is a continual cycle, what happens to birds during the winter affects their subsequent breeding season, often in unexpected ways, as new technology is revealing. Finally, since one of the greatest pleasures of watching birds is knowing how far some have traveled and how their physical and behavioral adaptations have enabled them to survive in what may be widely different environments, one surely wants to include the birds that winter where it may not seem like winter at all.

Another of the pleasures of watching birds is understanding more of whats really going on among the most familiar species that we may see all year or through the winter when many birds are so much more visible. In the midlatitudes, where in winter there may be no concealing foliage, it is much easier to follow birds through the day. Many also seem tamer, perhaps because of hunger and, in extreme cold, their tendency to reduce movement to save energy. Naive young birds living through their first winter sometimes give us glimpses experienced adults do not allow. I have seen a first-year Red-tailed Hawk bathing in a stream and a young Northern Goshawk carelessly bold.