contents

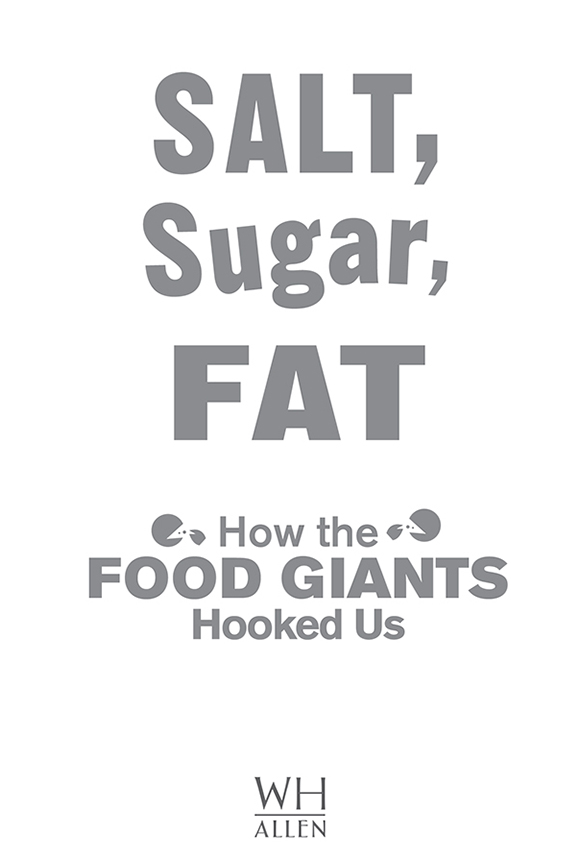

salt fat

salt sugar

sugar fat

about the book

In China, for the first time, the people who weigh too much now outnumber those who weigh too little. In Mexico, the obesity rate has tripled in the past three decades. In the UK over 60 per cent of adults and 30 per cent of children are overweight, while the United States remains the most obese country in the world.

We are hooked on salt, sugar and fat. These three simple ingredients are used by the major food companies to achieve the greatest allure for the lowest possible cost.

Here, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter Michael Moss exposes the practices of some of the most recognisable (and profitable) companies and brands of the last half century.

This is an eye-opening and explosive journey into the secretive world of the processed food industry that could change the way we eat. For ever.

Are you ready for the truth about whats in your shopping basket?

about the author

Michael Moss was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting in 2010, and was a finalist for the prize in 2006 and 1999. He is also the recipient of a Loeb Award and an Overseas Press Club citation. Before coming to The New York Times, he was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, Newsday and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife and two sons.

Also by Michael Moss

Palace Coup

For EVE, AREN, AND WILL,

my all and everythings

prologue

The Company Jewels

M inneapolis was having a blustery spring evening on April 8, 1999, when a long line of town cars and taxis pulled up to the office complex on South 6th Street and discharged their well-dressed passengers. These eleven men were the heads of Americas largest food companies. Among them, they controlled seven hundred thousand employees and $280 billion in annual sales. And even before their sumptuous dinner was served, they would be charting a course for their industry for years to come.

There would be no reporters at this gathering. No minutes taken, no recordings made. Rivals any other day, the CEOs and company presidents had come together for a meeting that was as secretive as it was rare. On the agenda was one item: the emerging epidemic of obesity and how to deal with it.

Pillsbury was playing host at its corporate headquarters, two glass and steel towers perched on the eastern edge of downtown. The largest falls on the Mississippi River rumbled a few blocks away, near the historic brick and iron-roller mills that, generations before, had made this city the flour-grinding capital of the world. A noisy midwestern wind gusting to 45 miles an hour buffeted the towers as the executives boarded the elevators and made their way to the thirty-first floor.

A top official at Pillsbury, fifty-five-year-old James Behnke, greeted the men as they walked in. He was anxious but also confident about the plan that he and a few other food company executives had devised to engage the CEOs on Americas growing weight problem. We were very concerned, and rightfully so, that obesity was becoming a major issue, Behnke recalled. People were starting to talk about sugar taxes, and there was a lot of pressure on food companies. As the executives took their seats, Behnke particularly worried about how they would respond to the evenings most delicate matter: the notion that they and their companies had played a central role in creating this health crisis. Getting the company chiefs in the same room to talk about anything, much less a sensitive issue like this, was a tricky business, so Behnke and his fellow organizers had scripted the meeting carefully, crafting a seating chart and honing the message to its barest essentials. CEOs in the food industry are typically not technical guys, and theyre uncomfortable going to meetings where technical people talk in technical terms about technical things, Behnke said. They dont want to be embarrassed. They dont want to make commitments. They want to maintain their aloofness and autonomy.

Nestl was in attendance, as were Kraft and Nabisco, General Mills and Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Mars. The companies present were the dominant players in processed industrial food, fiercely aggressive competitors who, when not gathering in secret, were looking to bludgeon one another in the grocery store.

Just that year per serving as Lucky Charms, the companys cloyingly sweet, marshmallow-filled cereal. And yet, because of yogurts well-tended image as a wholesome, life-giving snack, sales of Yoplait were soaring, with annual revenue topping $500 million. Emboldened by the success, General Mills development wing pushed even harder, inventing a yogurt that came in a squeezable tubeperfect for kidseliminating the need for a spoon. They called it Go-Gurt, and rolled it out nationally in the weeks before the CEO meeting. (By years end, it would hit $100 million in sales.)

So while the atmosphere at the meeting was cordial, the CEOs were hardly friends. Their stature was defined by their skill in fighting each other for what they called stomach share, or the amount of digestive space that any one companys brand can grab from the competition. If they eyed one another suspiciously that evening, it was for good reason. By 2001, Pillsburys chief would be gone and the 127-year-old companywith its cookies, biscuits, and toaster strudelwould be acquired by General Mills.

Two of the men at the meeting rose above the fray. They were here to represent the industry titans, Cargill and Tate & Lyle, whose role it was to supply the CEOs with the ingredients they relied on to win. These were no run-of-the-mill ingredients, either. These were the three pillars of processed food, the creators of crave, and each of the CEOs needed them in huge quantities to turn their products into hits. These were also the ingredients that, more than any other, were directly responsible for the obesity epidemic. Together, the two suppliers had the salt, which was processed in dozens of ways to maximize the jolt that taste buds would feel with the very first bite; they had the fats, which delivered the biggest loads of calories and worked more subtly in inducing people to overeat; and they had the sugar, whose raw power in exciting the brain made it perhaps the most formidable ingredient of all, dictating the formulations of products from one side of the grocery store to the other.

James Behnke was all too familiar with the power of salt, sugar, and fat, having spent twenty-six years at Pillsbury under six chief executive officers. A chemist by training with a doctoral degree in food science, he became the companys chief technical officer in 1979 and was instrumental in creating a long line of hit products, including microwavable popcorn. He deeply admired Pillsbury, its employees, and the warm image of its brand. But in recent years, he had seen the endearing, innocent image of the Pillsbury Doughboy replaced by news pictures of children too obese to play, suffering from diabetes and the earliest signs of hypertension and heart disease. He didnt blame himself for creating high-calorie foods that the public found irresistible. He and other food scientists took comfort in knowing that the grocery store icons they had invented in a more innocent erathe soda and chips and TV dinnershad been imagined as occasional fare. It was society that had changed, changed so dramatically that these snacks and convenience foods had become a dailyeven hourlyhabit, a staple of the American diet.

Behnkes perspective on his lifes work, though, began to shift when he was made a special advisor to Pillsburys chief executive in 1999. From his new perch, Behnke started to get a different view of what he called the big tenets of his industrytaste, convenience, and cost. He worried, especially, about the economics that drive companies to spend as little money as possible in making processed foods. Cost was always there, he told me. Companies had different names for it. Sometimes they were called PIPs, or profit improvement programs, or margin enhancements, or cost reduction. Whatever you want to call it, people are always looking for a less expensive way.

Next page