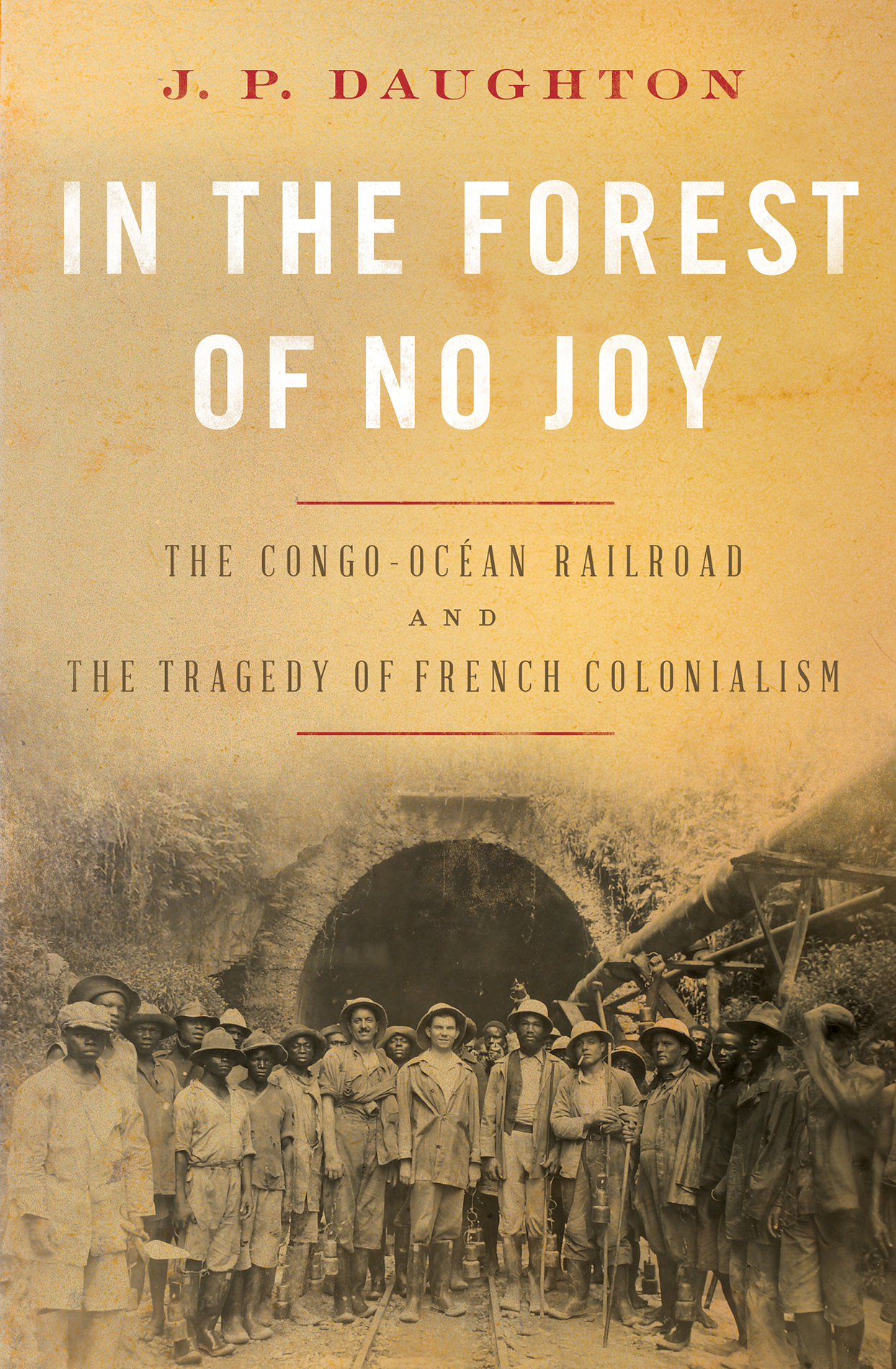

IN THE FOREST

of NO JOY

THE CONGO-OCAN RAILROAD

AND THE

TRAGEDY OF FRENCH COLONIALISM

J. P. DAUGHTON

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

For Karyn, Nathaniel, and Henry

O earth, cover not my blood, and let my cry have no place.

JOB 16 : 18

ALSO BY J. P. DAUGHTON

An Empire Divided: Religion, Republicanism, and the Making of French Colonialism, 18801914

IN THE FOREST of NO JOY

Map of French Equatorial Africa, c. 1920

Reception at the home of Marcel Rouberol, January 1, 1925

A worker and a sick young woman, c. June 1925

On the hunt between Pointe-Noire and Cte Mateva, August 1924

The construction site at Kilometer 53, March 1925

... and this only costs us 2,000 negroes per kilometer!!! Le Journal du peuple, April 28, 1929

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, 1905, portrait by Nadar

Brazza on the cover of Le Petit Journal, March 19, 1905

Governor-General Raphal Antonetti in his Paris apartment, 1932

Andr Gide with Marc Allgret in French Equatorial Africa, 1926 or 1927

A French administrator in French Congo, postcard, c. 1905

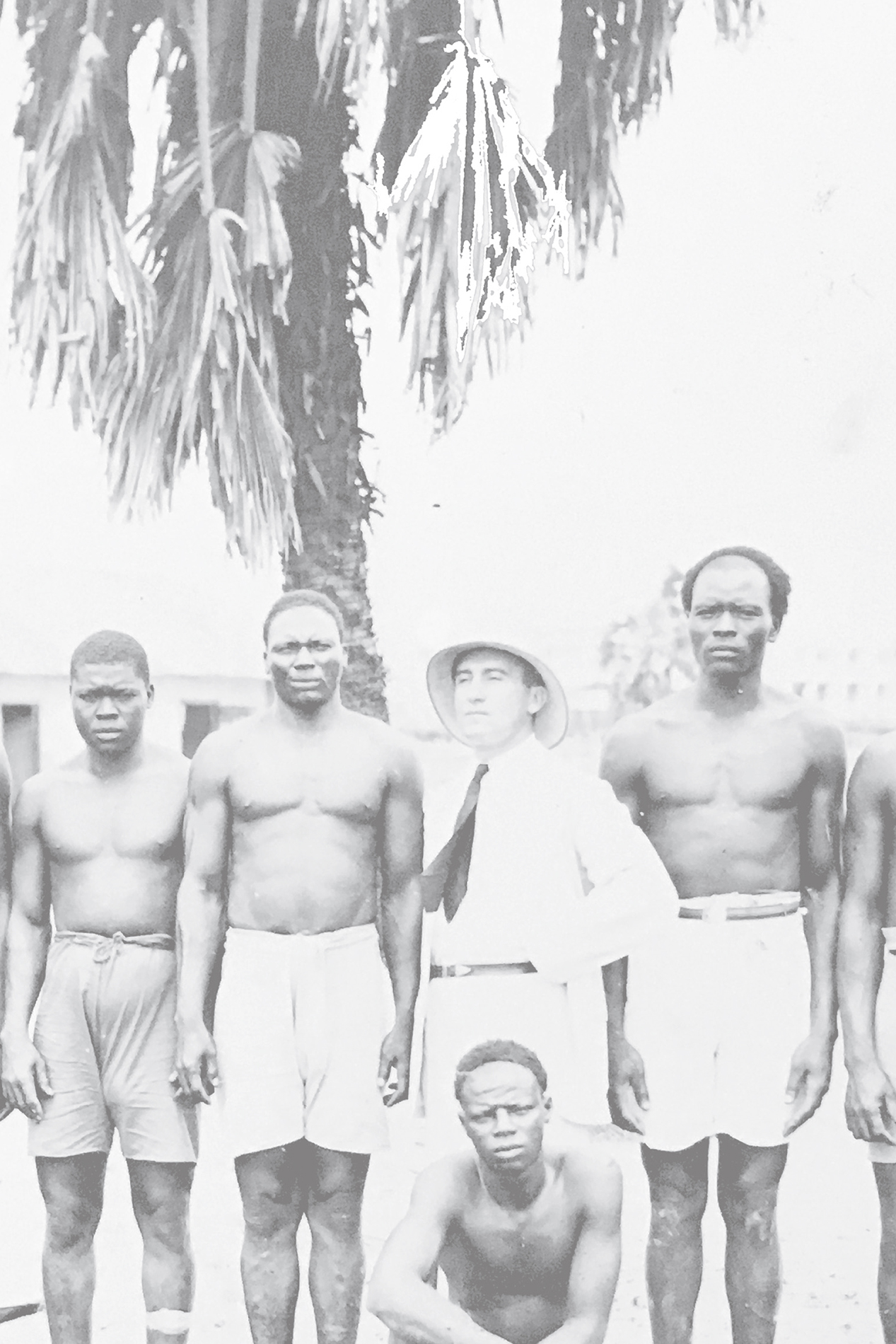

Workers from Chad or Ubangi-Shari, with a French administrator, c. 1926

Route and corresponding altitude of the Congo-Ocan railroad

In the Mayombe French Congo, postcard, c. 1910

A woman of MBoukou, c. 1925

A work team, c. 1925

A team of sick workers at Kilometer 61, Mavouadi, June 1925

The tunnel at Kilometer 109, Brazzaville side, September 1932

The viaduct at Kilometer 108, September 1932

A viaduct comprising nine ten-meter arches, Kilometer 140 in the Mayombe, 1934

Workers and overseers at the entrance to the Bamba tunnel, c. 1933

OF THOUSANDS GONE

Utopians are heedless of methods.

J. RODOLFO WlLCQCK

ON NEW YEARS DAY 1925, Marcel Rouberol, the chief representative of the Socit de construction des Batignolles, one of the largest French engineering firms at the time, held a reception at his home near Pointe-Noire for the men who worked under him. It was one of many gatherings that company employees organized to fight the boredom, homesickness, and sense of isolation that came with living and working on an inclement expanse of sand thousands of miles from home.

From 1921 to 1934, men from the Batignolles lived near the coast in Middle Congo, often referred to by the French as simply the Congo, a region in the southern part of French Equatorial Africa. They worked on building the Congo-Ocan railroad, a massive construction project that the colonial government undertook in the years just after the First World War. Long heralded by Frenchmen as essential to the economic development of the region, the railroad would connect the city of Brazzaville, the colonys largest settlement on the upper Congo River, to Pointe-Noire, on the Atlantic coast, where the French planned to build a deepwater port. Covering only some 512 kilometers, fewer than 320 miles, the railroad was not terribly long. But it crossed difficult terrain, especially the dreaded Mayombe, where the rails wound atop unstable, sandy soil, through a region of thick forests, mountains, and gorges.

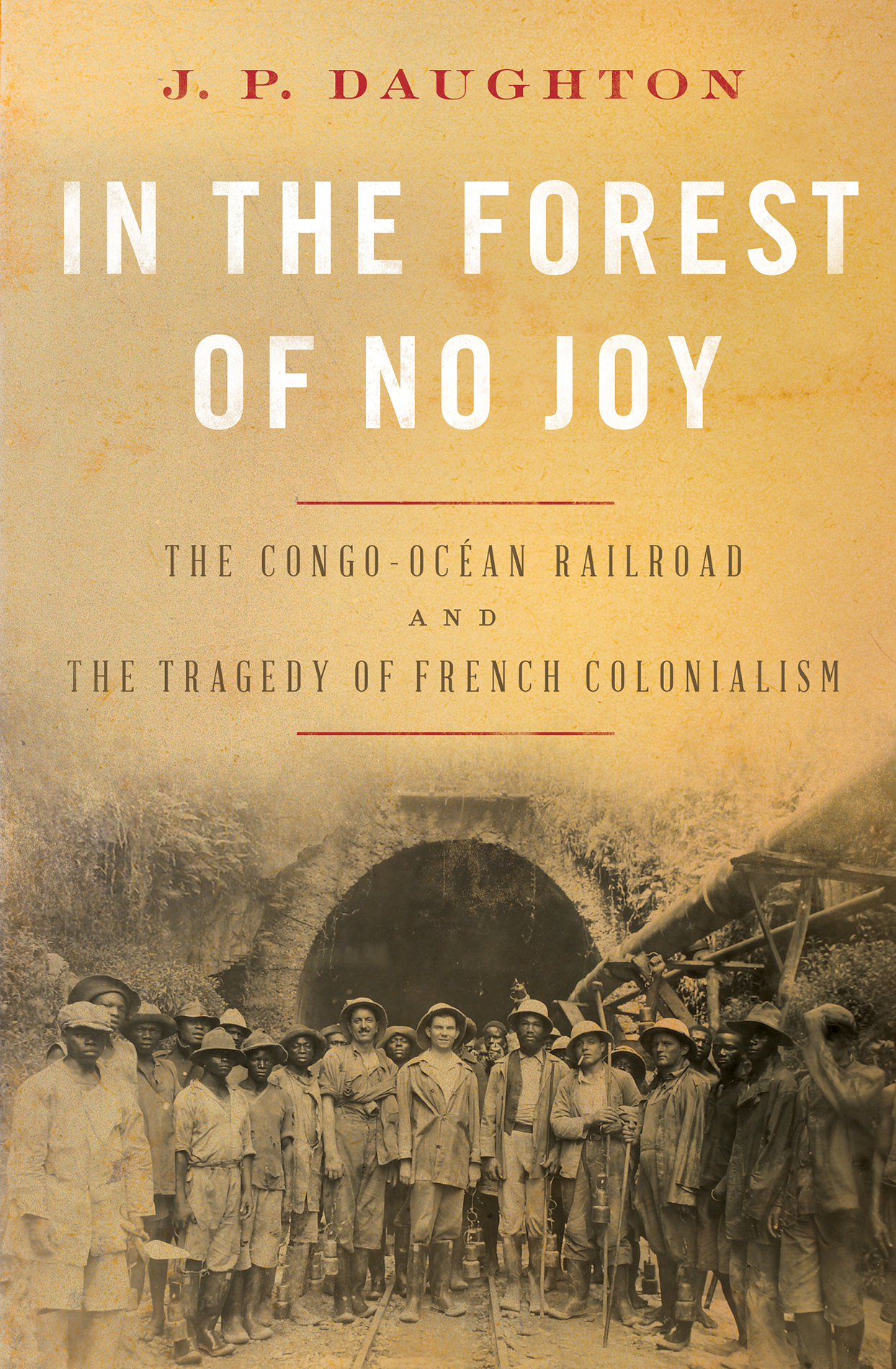

Reception at the home of Marcel Rouberol, January 1, 1925. Rouberol is in the front row, third from left, and Mr. Martin, also in the front row, is fourth from left.

A day like New Years was worthy of a photographeighteen white men, all in pressed white linen suits, each with his white pith helmet in his hand. Corporations are built on hierarchies, so placement and positioning were essential in the picture, which was to be sent to company headquarters in Paris. The two men front and center are Rouberol and M. Martin, the lead engineer on the construction site. Around them are engineers, administrators, and overseers of the project. Two African auxiliaries, perhaps assistants or secretaries, lacking white linen and helmets, are wedged against the right edge of the image, one of them literally cut off by the frame, behind their white superiors.

The Batignolles men exuded confidence on that New Years Day, none more so than Rouberol himself: his trimmed beard, neat tie, and impeccably white shoes complemented the self-assured smile on his face. Receptions like this one allowed these men and a handful of wives to come together and celebrate their accomplishments and discuss the work ahead. Despite their distance from France, executives of the Batignolles recreated some of the comforts of home. Boats from Europe brought in not only supplies to build the railroad but regular shipments of garlic, onions, and potatoes; refrigerated cheeses and charcuterie; jams and butter; rum, wine, and Mot champagne; Vichy and Perrier mineral water; coffee, Cointreau, and cigars. A New Years party was just the place to enjoy all that civilization could offer.

Despite the inclement weather and prevalence of disease, the white men in the photograph, all well fed and standing tall, appeared to be paragons of camaraderie, cleanliness, and health. The photo was a testament to Frances determination to triumph over the climate and landscape in a part of the world that Europeans considered insalubrious and uncivilized. The men of the Batignolles, as well as champions of the railroad in France, heralded the Congo-Ocan as an engineering colossus achieved in the deadly wilds of the African continent. It would, as one newspaper put it, save Equatorial Africa, regularly called the Cinderella of the French Empire, and open the regions nearly limitless reservoir of riches.

While this portrait of colonial power is telling in many ways, there is another story that it does not telland that it in fact hides in its straightforward simplicity. Just a short walk from the New Years celebration was the construction site of the Congo-Ocan where African men and women worked ten hours a day, six days a week, clearing millions of cubic meters of earth, building bridges and tunnels, and laying the ties and rails of the train line. For the thirteen years of construction, the workers wore minimal clothes and lived communally in huts so crowded and poorly ventilated that many chose to sleep outdoors. They faced overseers, both European and African, who often verbally tormented and beat them. They survived on a starvation diet and often went days without eating. Fresh water was in short supply, adding to the problem of dysentery that continually weakened the labor force, at certain points sickening or killing more than half the workers. Needless to say, French cuisine was never on the menu.

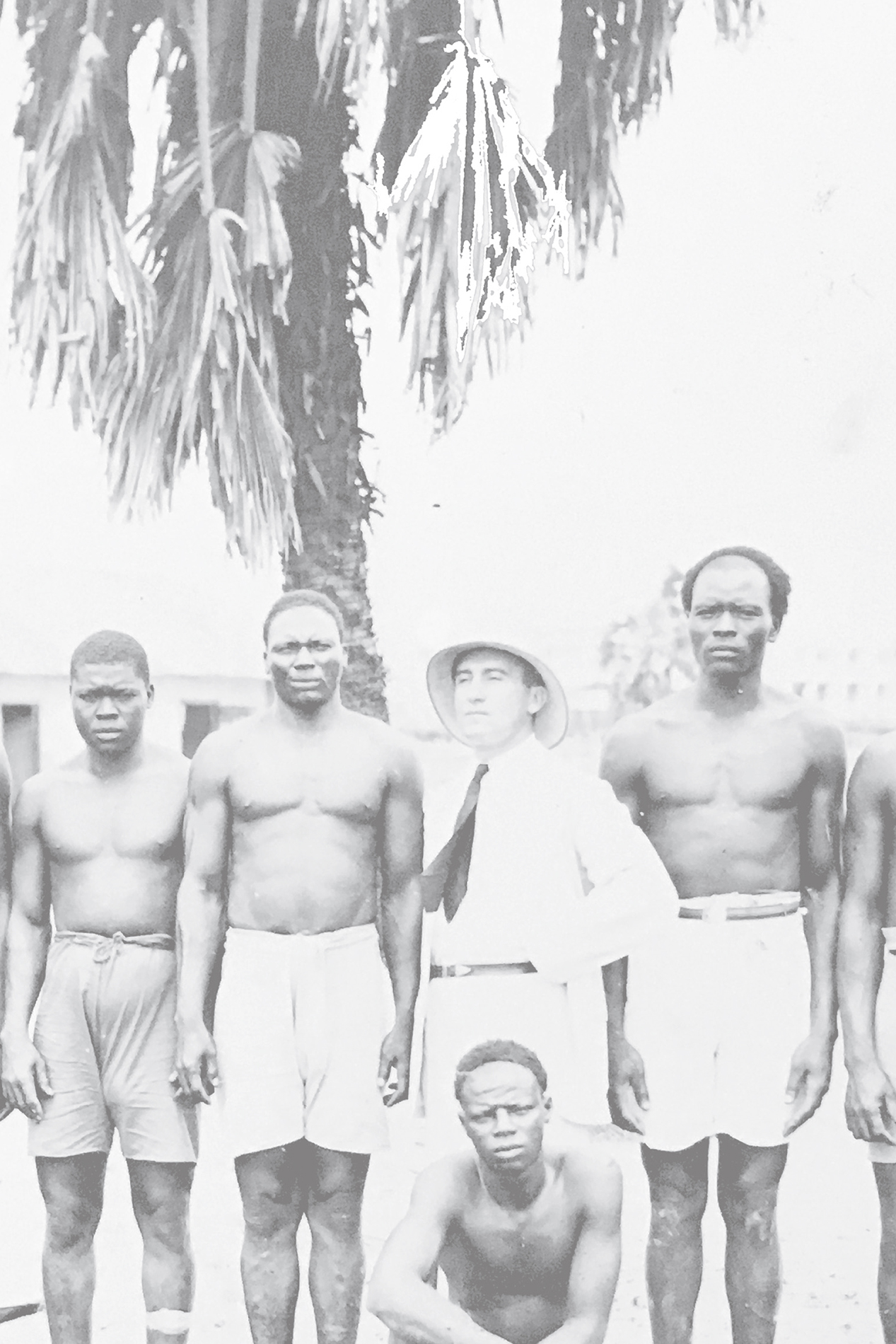

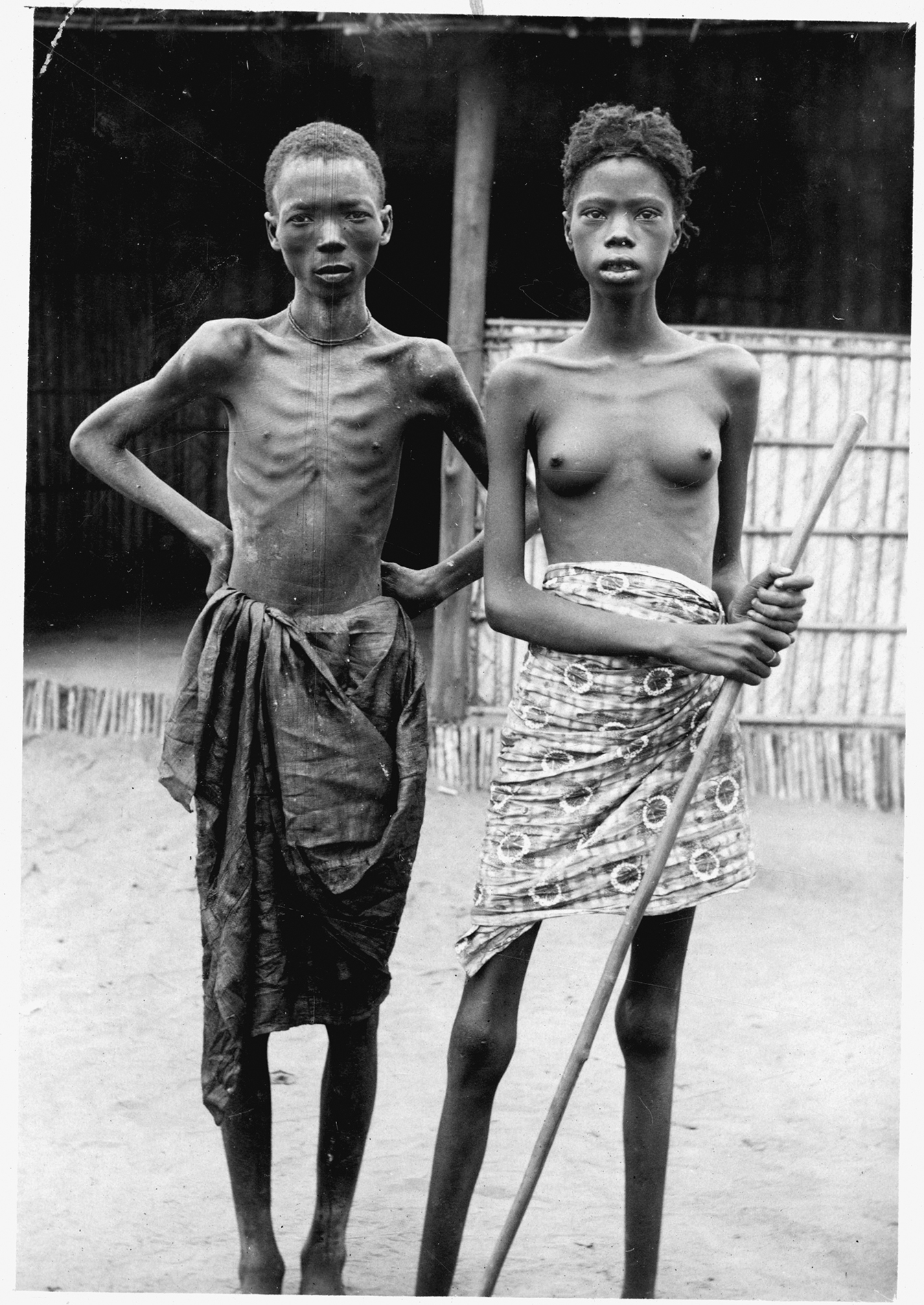

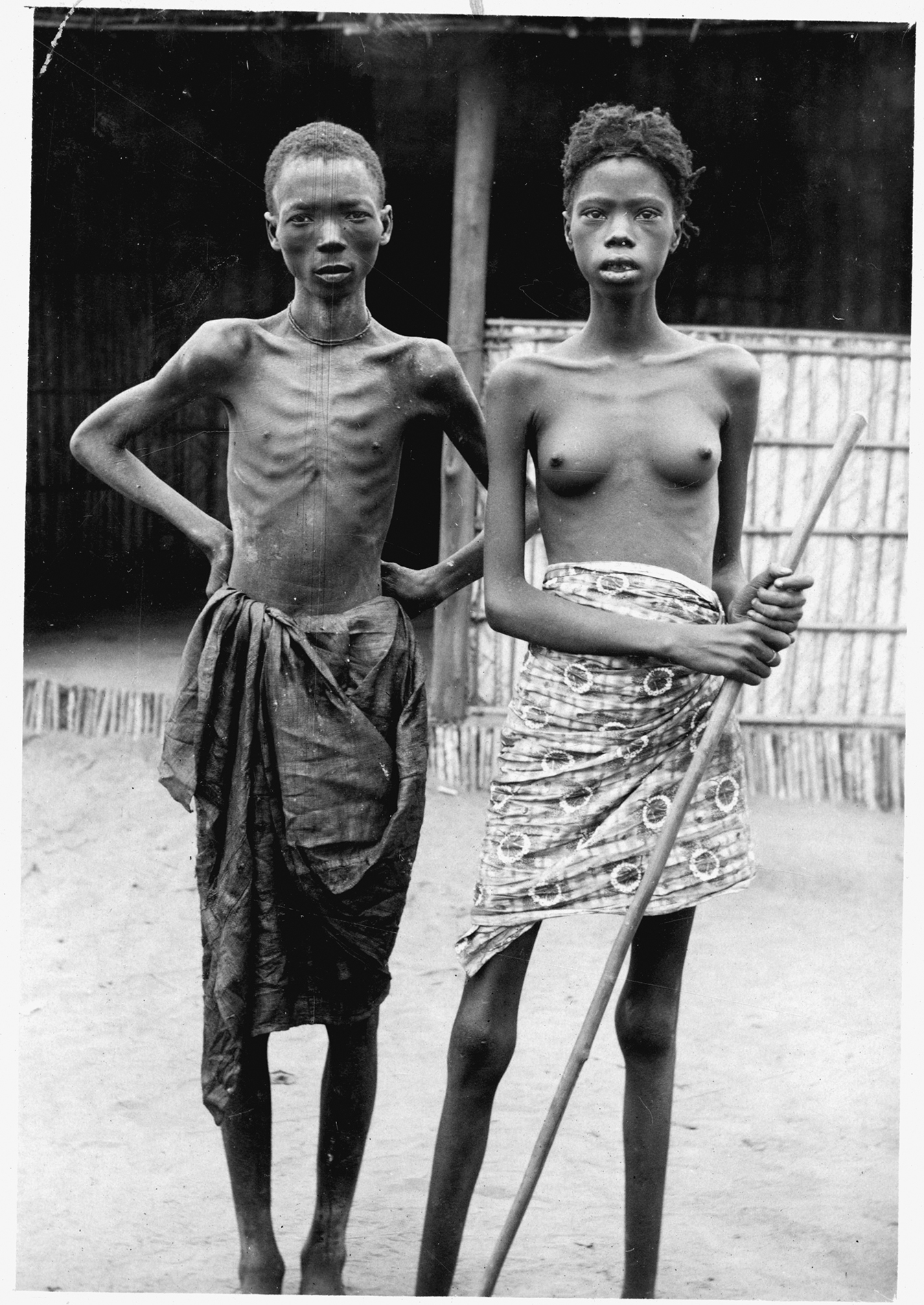

A sick young woman and worker, c. June 1925.

A second photograph, also taken in 1925 and not far from Rouberols home, brings the plight of these workers somewhat into focus. This image illustrates a very different side of the railroad project. The emaciated frames of these two unnamed people, identified only as a sick young woman and worker, suggest they suffered from severe malnutrition and perhaps dysentery or beriberi, a thiamine deficiency common among the poorly fed recruits. The cachexia, or extreme wasting, of their bodies is reminiscent more of famine victims or prisoners of war than of what the French insisted they werefree, protected laborers in a republican empire.

Next page