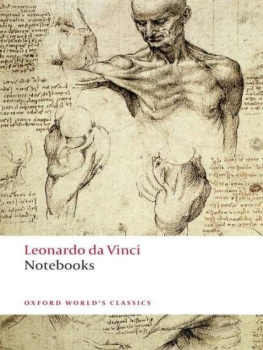

Leonardos Notebooks

Writing and Art of the Great Master

Edited by

H. ANNA SUH

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

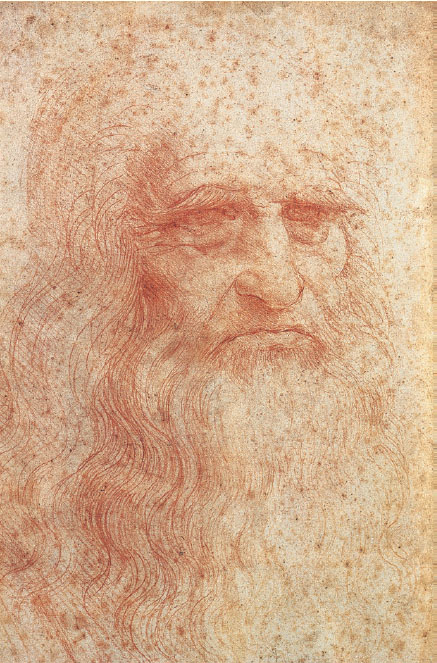

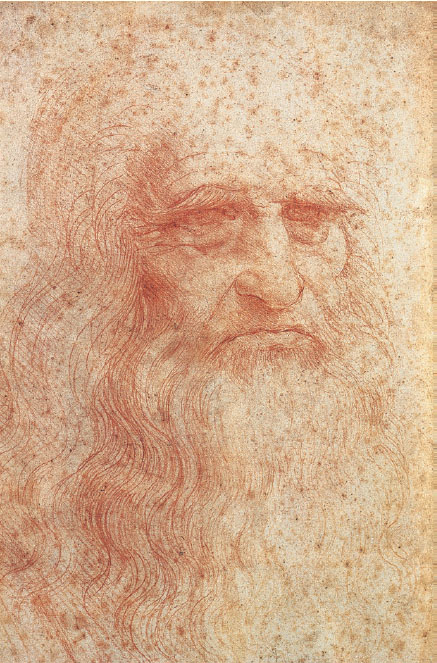

Five hundred years after the life of Leonardo da Vinci (14521519), this artist, inventor, and quintessential Renaissance man continues to fascinate and mystify us. In addition to his dozen or so enigmatic and beautiful paintings, Leonardo left an extensive body of sketches, notes, and writing, which resonates with a modern audience no less than they did with his admiring contemporaries.

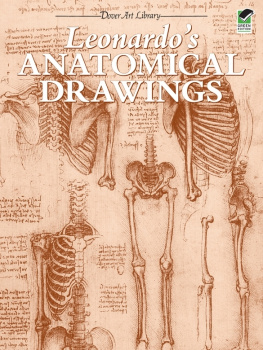

Comprising some four thousand pieces of paper, what are loosely called Leonardos notebooks are actually several different collections and compilations of his manuscripts. Ranging from subjects as diverse as anatomical studies to the details of grinding and mixing pigments, they offer nearly unfettered access to the great masters fertile imagination.

While Leonardos breathtaking draftsmanship has earned him well-deserved renown, his extensive writings are less well known. They present a challenge to the modern reader, not least because of his famous mirror writing, which did not result from dyslexia or a paranoid need for secrecy, as often thought. It was simply his characteristically resourceful solution to the challenges faced by all left-handed writers, who tend to smear ink with their hands as they move from left to right.

In addition, the notebooks are widely scattered and, with a few notable exceptions such as the Codex Leicester and the Codex Madrid, treat a vast range of subjects, sometimes even within a single page. Combined with the language barrier and the relative scarcity of translated materials, a further exploration of Leonardos genius can devolve into an exercise in frustration for the interested lay reader.

This volume is an attempt to overcome these difficulties. Aside from the editorial introductions to each section, the book is composed entirely of Leonardos own images and writings. They are presented in an edited format, and organized into chapters and sections. Although this categorization takes some liberties with Leonardos highly syncretic approach to his endeavors, it is intended to provide a more comfortable structure for the contemporary reader.

Largely self-taught, Leonardo had a chip on his shoulder about his lack of classical education, stating several times that he learned from empirical evidence and his (formidable) powers of observation. This autodidactic approach resulted in an unconventional approach to all his endeavors, from the depiction of landscapes to the construction of war machines. It is hoped that this book will bring the genius of Leonardo da Vinci to a new audience.

H. Anna Suh

EDITORS NOTE

Numbers preceding texts refer to the illustrations that bear the same numbers. Some illustrations are pertinent to more than one text and therefore appear more than once throughout the book. Text in italics refers to exact text matches with the writing on the illustration. In cases where there are several blocks of text on a single illustration, both the original blocks of text and the translated text are marked with corresponding letters.

This book is not a scholarly work of academic research. For those interested in further readings in the vast body of scholarship on Leonardo, essential bibliographies of English, French, German, and Italian sources are provided at the end of the volume.

Part I

Beauty, Reason, and Art

Leonardo da Vincis modern-day reputation rests largely on his artistic accomplishments. During a time of remarkable developments in the techniques and expressive possibilities of pictorial art, Leonardos contributions were especially valuable. He combined his interests in observation and experimentation with a keen aesthetic sensibility and unparalleled artistic skills to produce a remarkable body of sketches and writings on different aspects of pictorial representation.

This section introduces his thoughts and instructions on different aspects of the painters craft. On Painting presents his general ideas about the essentials of paintings, such as the role of light in compositions, guidelines for different kinds of paintings, and tips for the aspiring painter. Human Figures compiles Leonardos extensive studies of proportion and balance in the depiction of the human body, considered the noblest subject of Renaissance art. Light and Shade consists of his meticulous studies on the interplay of bright and dark in painting.

In Perspective and Visual Perception, Leonardo contributes to the landmark accomplishment of the Renaissancethe techniques of creating a realistic space within the picture plane. These techniques derived from a realization that as objects recede into the distance, they are proportionally reduced in size, color clarity, and detail. Leonardo was a master of these various kinds of perspective, as demonstrated by his characteristic sfumato, or smoky atmospheric effects in such paintings as the Mona Lisa and his Virgin and Child with Saint Anne.

And in Studies and Sketches, a number of his studies, including those for his famous fresco of The Last Supper, appear alongside his remarkable notes for these projects. This section also includes images of allegorical and fantastic creatures, which demonstrate that Leonardo, for all his faith in the powers of observation, also had a powerfully creative imagination.

The first drawing was a simple line drawn round the shadow of a man cast by the sun on a wall.

I. On Painting

[1]

[1]

The mind of the painter must resemble a mirror, which always takes the color of the object it reflects and is completely occupied by the images of as many objects as are in front of it. Therefore you must know, O Painter! that you cannot be a good one if you are not the universal master of representing by your art every kind of form produced by nature. And this you will not know how to do if you do not see them, and retain them in your mind. Hence as you go through the fields, turn your attention to various objects, and, in turn, look now at this thing and now at that, collecting a store of diverse facts selected and chosen from those of less value.

But do not do like some painters who, when they are wearied with exercising their fancy dismiss their work from their thoughts and take exercise in walking for relaxation, but still keep fatigue in their mind, which, though they see various objects [around them], does not apprehend them; but even when they meet friends or relations, saluted by them, although they them, take no more cognizance if they had met so much empty air.

Painting surpasses all human works by the subtle considerations belonging to it. The eye, which is called the window of the soul, is the principal means by which the central sense can most completely and abundantly appreciate the infinite works of nature; and the ear is the second, which acquires dignity by hearing of the things the eye has seen. If you, historians, or poets, or mathematicians had not seen things with your eyes you could not report of them in writing.

And if you, O poet, tell a story with your pen, the painter with his brush can tell it more easily, with simpler completeness and less tedious to be understood. And if you call painting dumb poetry, the painter may call poetry blind painting. Now which is the worse defect? To be blind or dumb? Though the poet is as free as the painter in the invention of his fictions, they are not so satisfactory to men as paintings; for, though poetry is able to describe forms, actions, and places in words, the painter deals with the actual similitude of the forms, in order to represent them. Now tell me which is the nearer to the actual man; the name of man or the image of the man? The name of man differs in different countries, but his form is never changed but by death.

Next page