An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

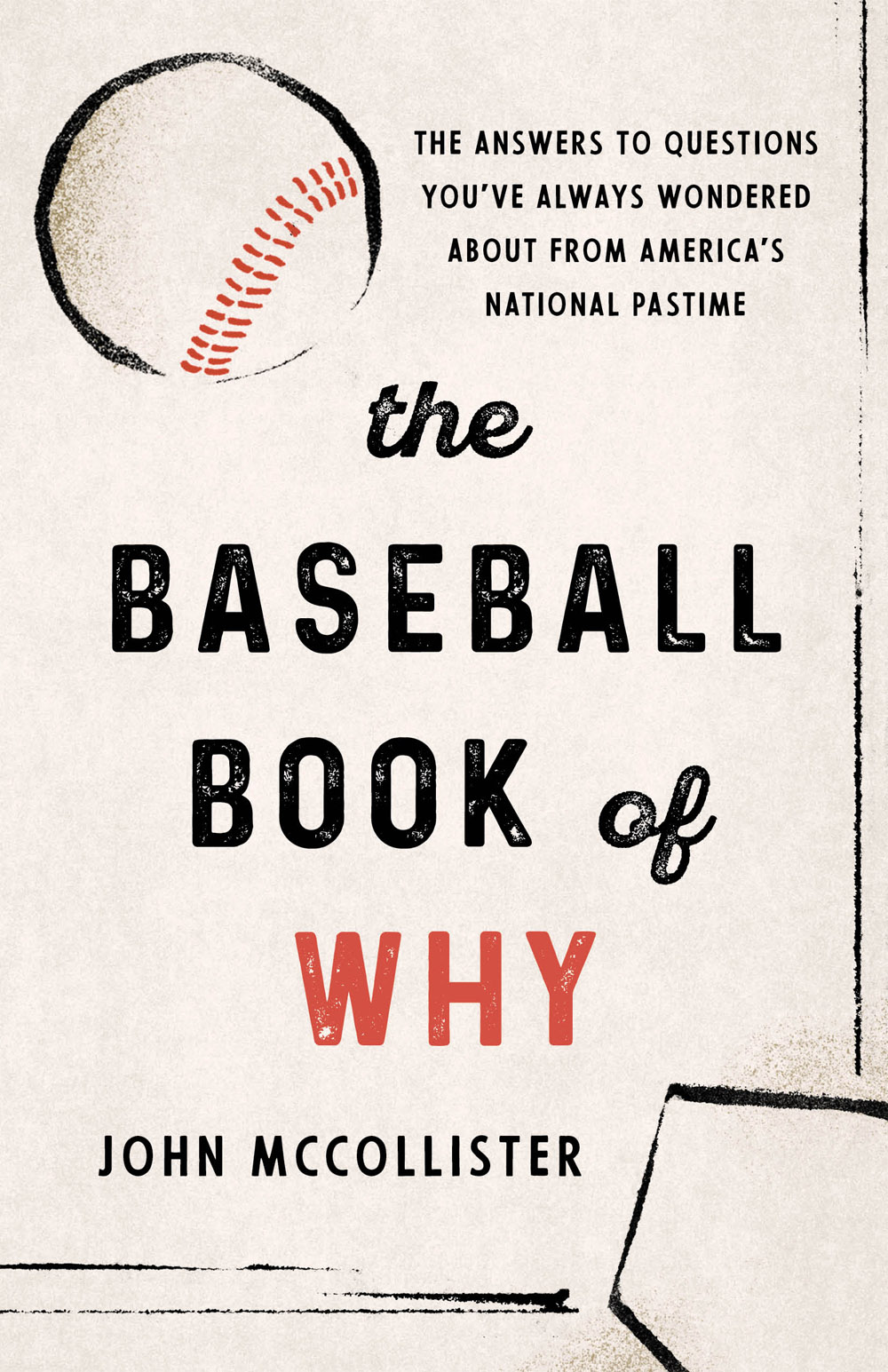

Copyright 2020 by John McCollister

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019957519

ISBN 978-1-4930-4887-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-4888-5 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Contents

Guide

Why?

That tiny, seemingly innocent word has driven people, even nations, to examine the reasons we began the traditions we accept as a normal part of our lives.

Fans of baseball know this all too well.

Yet, modern-day enthusiasts of what has been deemed Americas Pastime are not always of the same opinion as to why some tradition may have begun. Loyalties are often dictated by the team for which they cheered as youngsters. High-powered business executives wear replicas of team jerseys to an important meeting on Wall Street. Teens wear T-shirts spelling out in bold print a particular ball club.

One thing that unites them all, however, is an appreciation of the sport that begat these traditions.

Thats what this book is all about.

Some of the answers to these questions, each of which begins with that intriguing word why are brief and to the point. Others require more detail in order to give a meaningful response.

Whatever the case, this writer hopes that each question and answer in this volume will allow the reader to appreciate, even more, the greatest sport ever created.

No book is ever written in a vacuum. I relied on friends of baseball without whose help the production of this volume would have been impossible.

Special thanks goes to Pittsburgh-based marketing and public relations consultant Todd Miller for editing and fact-checking this manuscript.

Thanks also to Rick Rinehart of Rowman and Littlefield for his guidance and support throughout the creative stages of this project. You are the absolute greatest.

Baseball announcers as well as other fans of the game, perhaps in an attempt to insert an extra dimension of variety into the broadcast, will sometimes refer to the pitcher on the mound as a southpaw if hes a left-handed thrower. The reason is quite simple once you think about it.

Baseball stadiums are designed to have batters looking east or northeast. When a pitcher faces the batter, he receives the sign from the catcher and prepares to toss the pitch, be it a fastball, a curveball, or even a knuckler, with his body facing west. As a result, the left side of his body as well as his left arm are facing south. When the pitcher eventually lets go of the ball, hes releasing it from the south side of the mound.

Hence, hes called a southpaw.

Get it?

Throughout Major League Baseball, as well as within the minor and amateur leagues, when a pitcher on the mound nears the 100 mark in the total of his tosses, his manager, in all probability, will have notified his bullpen to alert one of the relief pitchers to prepare to enter the contest.

The reason is that most physical therapists and other medical experts are of the opinion that an athletes arm will endure this much strain before showing signs of fatigue.

Of course there are exceptions to this practice. One rather stunning example in modern times happened on July 2, 1963, in San Franciscos Candlestick Park when the Giants hosted the visiting Milwaukee Braves.

Neither team was setting the world ablaze, despite the fact that both squads featured some future Hall of Famers. The visiting Braves had the likes of Henry Aaron, Eddie Mathews, and Warren Spahn. San Francisco heralded Willie Mays, Orlando Cepeda, and Juan Marichal.

The aging Spahn (42 years old) no longer had his overpowering fastball, but he had developed a wicked curveball that left opposing hitters shaking their heads in awe and disbelief after seeing a third strike nip the lower outside corner of the plate.

His mound opponent, 25-year-old Marichal, was no slouch himself. In only his fourth year of big-league baseball, this high-kicking native of the Dominican Republic eschewed finesse to keep hitters off-balance with an overpowering fastball.

Both pitchers wasted no time in setting down their opponents in order in the first. And so it continued throughout the night as the temperature dipped below 60 degrees.

At the conclusion of regulation time, both pitchers said they could go on.

In spite of the rather cool temperature, most of the 15,921 fans in attendance stayed to watch what they anticipated was developing into a classic pitchers duel. Following each inning most of the sleepy-eyed fans rose and applauded to show their appreciation.

Each of the two pitchers waited for the other to blink.

But neither Spahn nor Marichal made a habit of blinking.

At 12:21 a.m., in the bottom of the 16th inning, after Harvey Kuenn grounded out, up to the plate stepped a heretofore hitless Mays. The Giants superstar swung at Spahns first pitch and smacked a towering fly ball to deep left-center field. The hometown crowd screamed with delight as they watched the ball disappear over the fence and into the chilly morning air.

The Giants won the game 10. But other numbers stood out more than the score: Marichal that night threw 227 pitches and Spahn, 201.

Those in attendance would not need any printed box score to remember the most important thing: they were fortunate to see one of the greatest baseball games ever played.

A PITCHER HAS TO LOOK AT THE HITTER AS HIS MORTAL ENEMY.

EARLY WYNN

Any baseball historian knows that Jack (the name he preferred, as opposed to Jackie) Robinson, of the old Brooklyn Dodgers, was the first person of color to be invited to join a Major League Baseball club.

Other talented ballplayers had aspirations of filling this designation in history, many of whom were relegated to teams in the so-called Negro League. But, according to many observers, there were three specific reasons why Robinson eventually was the one selected.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.