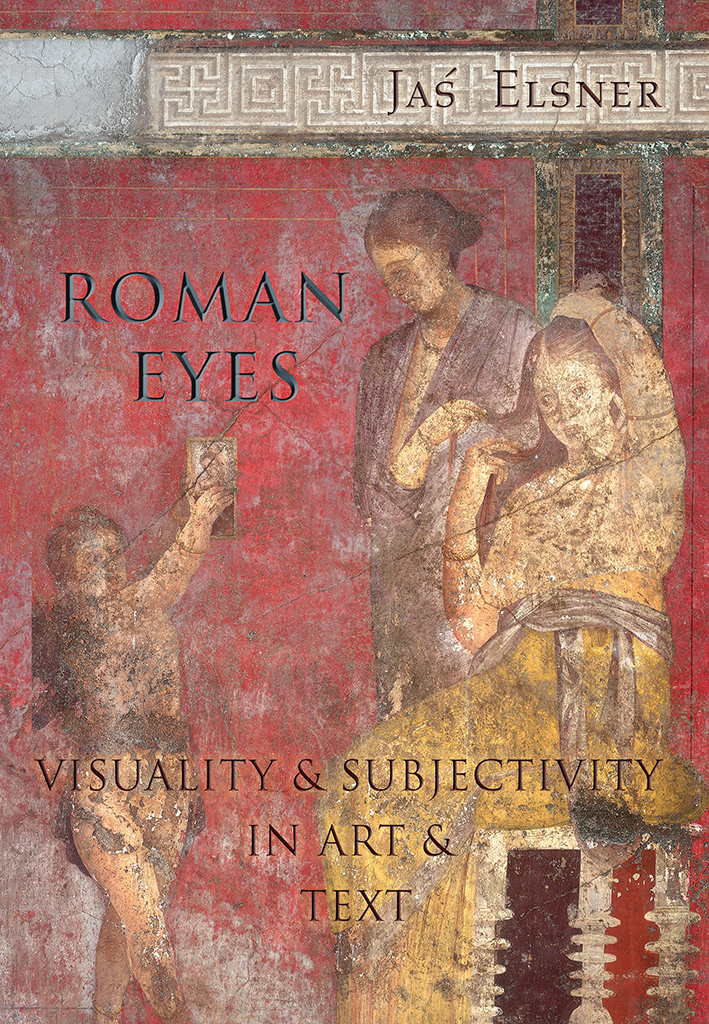

ROMAN

EYES

VISUALITY

& SUBJECTIVITY

IN ART & TEXT

ROMAN EYES

VISUALITY & SUBJECTIVITY IN ART & TEXT

Ja Elsner

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS | PRINCETON AND OXFORD

2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Elsner, Ja.

Roman eyes : visuality and subjectivity in art and text / Ja Elsner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-09677-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-09677-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Arts, Classical. 2. Aesthetics, Roman. 3. Visual Perception. I. Title.

NX448.5.E47 2007

700.937dc22 2006051366

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

pup.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-0-691-24024-4

R0

FOR FROMA

Whose idea it was

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK IS THE RESULT of a series of essays on related themes written over the last fifteen years. Most have been published earlier, in different forms; all those have been revised here. , in the course of rather different arguments, elsewhere as well. I thank the original publishers in detail below. Many people have helped me as I have worked on these studiestoo many to name individually, especially as one might easily but invidiously forget someone, given the length of time over which this project has evolved. But my gratitude is especially due to Froma Zeitlin, who is to be blamed for the idea of this book; to my classical colleagues at Corpus Christi College and my art historical colleagues in Chicago over the years, on whom quite a bit of this has from time to time been inflicted; and to my students at the Courtauld, Oxford, and Chicago, who have never let me get away without at least trying to make myself clear.

For their help and advice in the complex and arduous business of getting hold of photographs, I am particularly grateful to Lucinda Dirven, Milette Gaifman, Ted Kaizer, Roger Ling, Katerina Lorenz, Marlia Mango, Michael Padgett, Verity Platt, Susan Walker, Roger Wilson, Stephanie Wyler, and the photographic services of the British Museum and of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome. Ian Cartwright has been wonderful and indefatigable in his help with the digitizing of images. The Charles Oldham Fund at Corpus has generously supported the costs of reproducing, digitizating, and publishing these images. Thanks are due also to a number of providers of photographs for their willingness to waive reproduction fees in the case of a scholarly publication in the wider interest of academic research. This is a far-sighted policy which deserves applause, especially at a difficult time financially for public institutions. So I am happy to mention the British Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, the Cabinet des Mdailles at the Bibliothque Nationale in Paris, the German Archaeological Institute in Rome, and the Conway Library.

Finally, I am most grateful to the editorial team at Princeton University Press for their help and care with my manuscript. In particular, I should mention Ian Malcolm, Meera Vaidyanathan, Lys Ann Weiss, and Elizabeth Gilbert.

appeared as Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos, Classical Philology 96 (2001): 269304.

PROLOGUE

He gazed and gazed and gazed and gazed,

Amazed, amazed, amazed, amazed.

Robert Browning (18121889)

MY EPIGRAPH, A BRIEF POEM by Browning from about 1872 entitled Rhyme for a Child Viewing a Naked Venus in a Painting of the Judgment of Paris, captures many ramifications of the issues I want to address in this book. We may think that art is an objective matter of material objects to be studied, appreciated, and collected in the world out therein the case of Brownings poem, a painting of the Judgment of Paris. But when we turn to the gaze, we move from the material and the objective into the world of subjectivities. This is a realm of impression, fantasy, and creativityframed, certainly, by the particular objects on which the gaze may fasten in specific contextsbut nonetheless subject to all kinds of psychological (and indeed psychopathological) investments, both collective and individual, to which our historical, documentary, and visual sources usually fail to give access.

Of Brownings epigram, we may ask, is the reiteration of the gaze in the first line relentlessly intensitive, with the crescendo of amazement overwhelming the mind in line 2 as its result? Or do the ands of line 1 string together a range of gazesdifferent in kind, feeling, effectwhich give rise to a variety of amazements, discretely separated by the commas of line 2? Is the boyperhaps for the first time sexualised in his confrontation with female nuditycaught in the eddies of his own gaze, so that, Narcissus-like, he falls into a whirlpool of amazement, a maze of wonder from which the poem offers no extrication? In this reading the childs youth, indicated by the poems title, and gender become significant. Or do the ands of the first line indicate a dynamic and creative activity of investment (he gazed nd gazed nd gazed nd gazed), inverting the normal emphasis of the iambic rhythm, so that the boy fashions, Pygmalion-like, out of the picture an object worthy of his amazement? And what of the focalization? The title deliberately marks out not only a whole picture (and the long mythological ancestry of the Judgment of Paris in literary and art historical tradition) but also a specific element in that picture. Naked Venus toothe focalization of Brownings childs looking and amazementevokes a long art historical ancestry of famous artists and famous works, reaching back to Praxiteles and Apelles. But in looking at Venus, is the child amazed by her nuditythe sexuality of Naked Venusor by her divinity, the dazzling epiphany of an ancient god clothed in her usual accoutrements of nudity? Is the poems gaze and wonder directed at a specific picture (never exactly identified, never illustratedlike so many ladies addressed in love poems from antiquity to Brownings own English heritage)? Or is it, following the epigrams literary and textual dynamic as poetry, not rather a gaze of amazement at Classical themes in general (as much literary as visual) from the author of the Browning Version of Aeschylus Agamemnon?

The gaze, in Brownings recognition, is more than an object or an activity of the subject. It is active (he gazed in line 1), but its results are passive ([he was] amazed in line 2). The process cannot be separated from its effects; the viewers subjective link via the gaze to that which he sees (never stated in the poem, but only in its title) causes an internal effectamazementwhich may or may not alter that initial act of gazing. That processual linkage, a constant subjectivizing of the object so that what naked Venus provokes is all the intimations of four-fold amazement, is both the difficulty and the attraction of studying the gaze.

But beyond the poems specific immersion in the act of gazing and its amazing effects, the title signals a further and crucial dimension of the gaze. By making his epigram a rhyme for a child viewing... , Browning opens the possibility of disjunction between the gaze as such and the gaze observed. Is the child fully and ideally immersed in his gaze, or is he aware of the gaze of another watching him as he looks? Does every and in line 1 signal an increasing self-consciousness, so that the amazements are the effects of not simply the subject in confrontation with naked Venus but of the subjects performance of a socially conditioned and expected amazement for the benefit of an observing gaze of which he is consciously or unconsciously aware? If he is consciously aware of being observed, are his gaze and its results altogether an act? Has he turned himself into a picture to create an effect on the viewer he knows is watching him? If he is unconsciously awarethat is, if the act of gazing always carries the implicit sense that it may be observed and even reciprocated, then even in his most spontaneous and intimate response of amazement, is there a conditioned (even a policed) element of the sort of reaction a child in an art gallery ought to be offering when confronted with great art? The shift from the poems own apparent unselfconsciousness to a title which emphasizes looking at anothers looking cannot but suggest the problem of the consciousness of being looked at while looking. Alongside this move from the entirely subjective gaze to the gaze in an expanded sphere of reciprocal gazing, the poem performs a shift from looking to words about lookingfrom the preverbal response to art (gazed and amazed) to the artfully formulated expression of that response as a rhyme for a child. The opening of the epigrams title, Rhyme for a Child Viewing... , makes clear this move to the verbal and again undermines the apparently unmediated directness of the poems two lines with the reminder that they are a rhymethe careful exposition of experience through textual artifice. Again Browning implicitly raises the complex problems of the verbal nature of the gazeits dominance by words (at least when we think, talk, or rhyme about it) and the difficulty of ever conceiving it as free of words. In terms of both the place of the gaze in the wider field of gazing and the relation of the gaze to its verbal articulation, the juxtaposition of rhyme and title offers a potential series of worries highly pertinent to the problems of the gaze in connection with the art of the Roman world.