Preface

The Demon Metal

The world is searching for cobalt, the miracle ingredient of the digital age. The metals capacity to store energy and stabilize conductors has made possible the proliferation of rechargeable batteries, smartphones, and laptops. More crucially, in the face of catastrophic climate change, cobalt offers the hope of a clean-energy future. Access to reliable supplies of cobalt will be essential if we are to advance into the era of the mass-produced electric vehicle.

But cobalt has a much darker side. The relentless drive to feed the cobalt needs of Silicon Valley has led to appalling levels of degradation, child abuse, and environmental damage in the Democratic Republic of Congo (drc), the worlds number-one cobalt producer. The situation is so dire that human rights campaigners have denounced cobalt as the blood mineral of the twenty-first century.

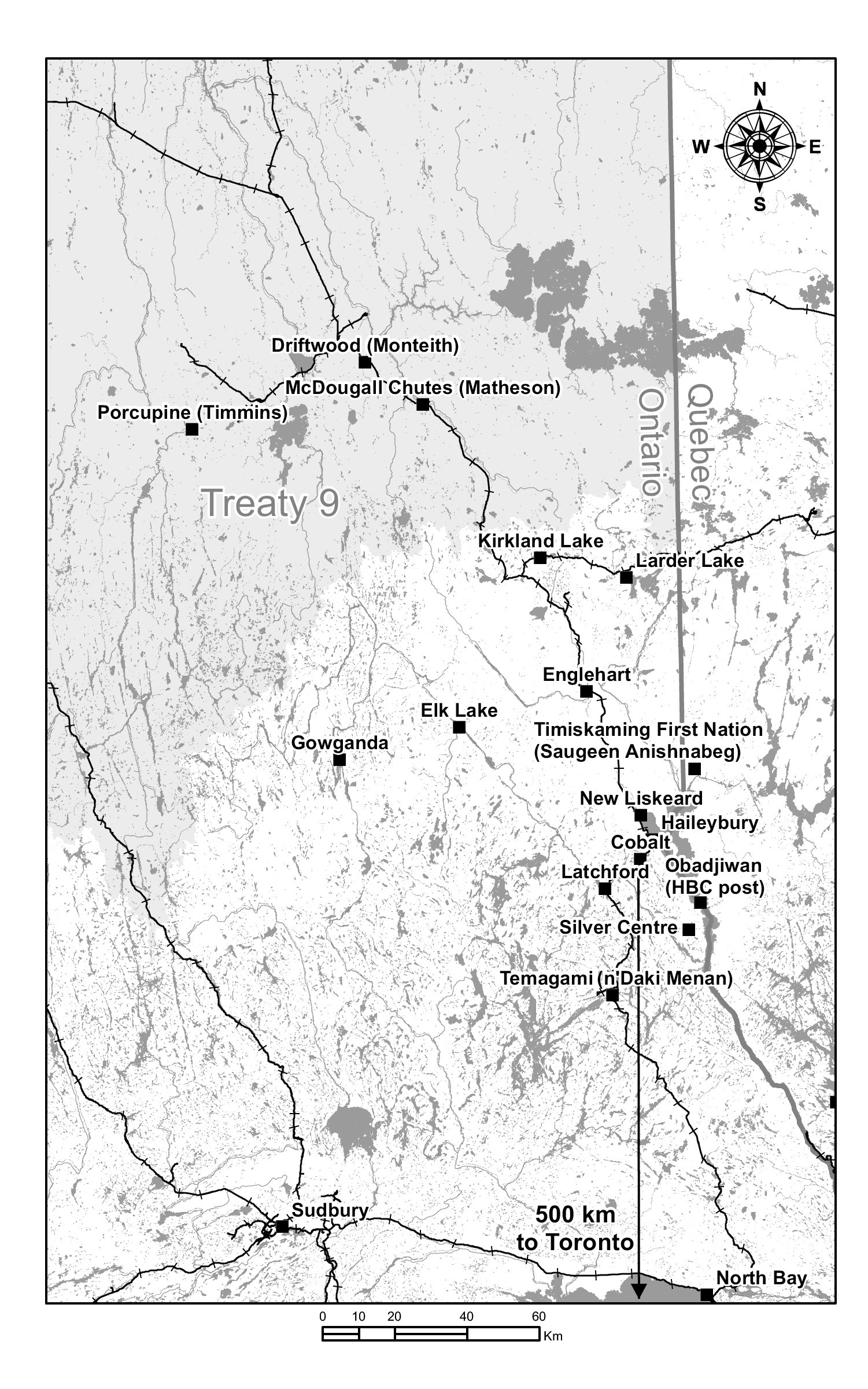

Tesla, Google, and Apple would love to cut their ties with the abuses in the drc, but cobalt is an extremely elusive metal. Thus, it is not surprising that, in 2020, billionaires Jeff Bezos, Michael Bloomberg, and Bill Gates formed a mining company to seek out new sources of cobalt in northern Canada. They named their company KoBold Metals.

Kobold is a variant of the German word for cobalt, derived from the kobalos, a satyr and shape-shifter in Greek mythology who mocked the work of humans. In the Middle Ages the kobalos became the kobold a demon living in the mines of Germany. The men who made their way into the perpetual darkness of the metal mines knew the demons were close from a burning sensation on their fingertips as they touched the cobalt-laced rock. And they knew the kobolds were watching them from the telltale sounds of banging and footsteps echoing through the caverns.

To anyone who has stood in the dark depths of an underground mine chamber, such superstitions are perfectly understandable. As miners dig deeper, the pressure from the millions of tons of earth above them increases. This pressure causes the weight around the underground openings to shift, eliciting a terrible groaning. Sometimes theres a loud banging like two boxcars hitting each other in a freight yard. Other times the pressure is more subtle like the sharp snap of a twig being stepped on, which evokes the deeply unsettling feeling of being stalked in the blackness.

Mining traditions around the world have variations of the legend of the kobold. In the silver mines of Bolivia, the miners leave offerings for El To the devil spirit. In Cornish mines, there are stories of the Knockers; Welsh miners worked alongside the Coblynau. In some cases, these creatures are condemned spirits, forced to work for eternity for no gain. In other cultures, the goblins help the miners by leading them to the ore.

For miners in Germany, the kobold held a particular menace. The metal was even denounced from the pulpit by a sixteenth-century Reformation firebrand who called it the black devil.

Little wonder that they feared the demon metal.

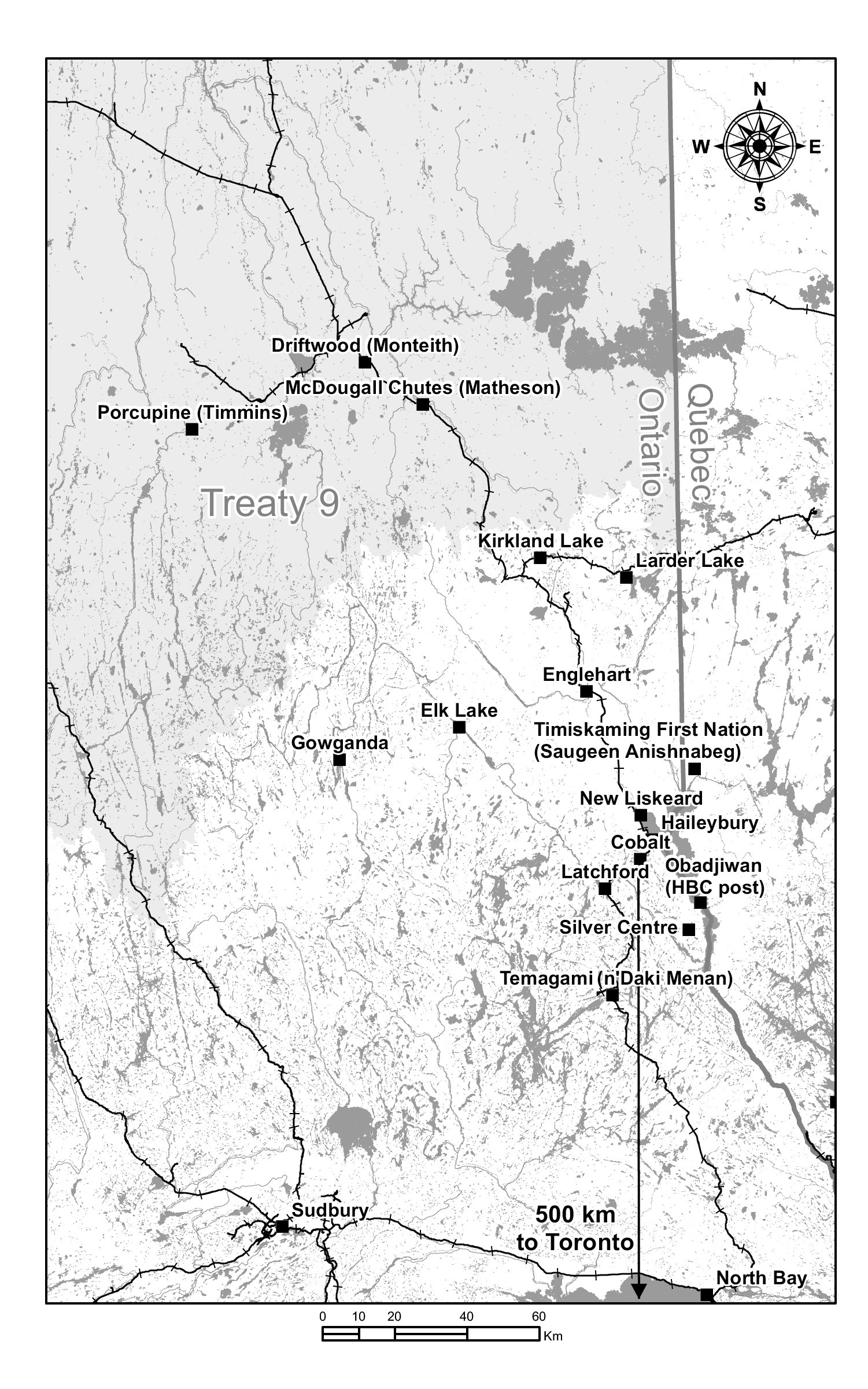

It is doubtful that todays billionaire class has reflected much on the dark power of the kobold. They are looking to strike the next great mineral rush, which is taking place within a broader geopolitical struggle to control the market in strategic metals. The cobalt rush has drawn investors back to a little town in Northern Ontario. A place called Cobalt.

There is a powerful synchronicity in this renewed interest in Cobalt, Ontario. This is not just some old mining town looking for one more chance to flourish. The events that took place here more than a century ago set Canada on its path to becoming the worlds preeminent resource extraction superpower. The country dominates the global industry; three-quarters of the worlds mining companies are registered in Canada. The maple leaf flies over international zones of resource exploitation ranging from uranium mines in the former states of the Soviet Union to gold projects in the Amazon to the metal deposits of Africa, where horrific human rights abuses are accepted as part of the cost of doing business.

To make sense of this, we need to return to Cobalt the place that let loose the demons of the earth.

Part One

Discovery

You can trace the lines on a map of a country,

chart your way to the heart of a country.

Explore, stake a claim: go down in history,

write your name on a spot on a map, claim you found it

but does that make it yours?

What does discover mean?

To be pointed in the right direction, by someone who will not be named,

Someone who knows the frozen land like the back of their weathered hand

Someone about whom no songs will be written.

Evalyn Parry,

To Live in the Age of Melting:

Northwest Passage

One

Origin Stories

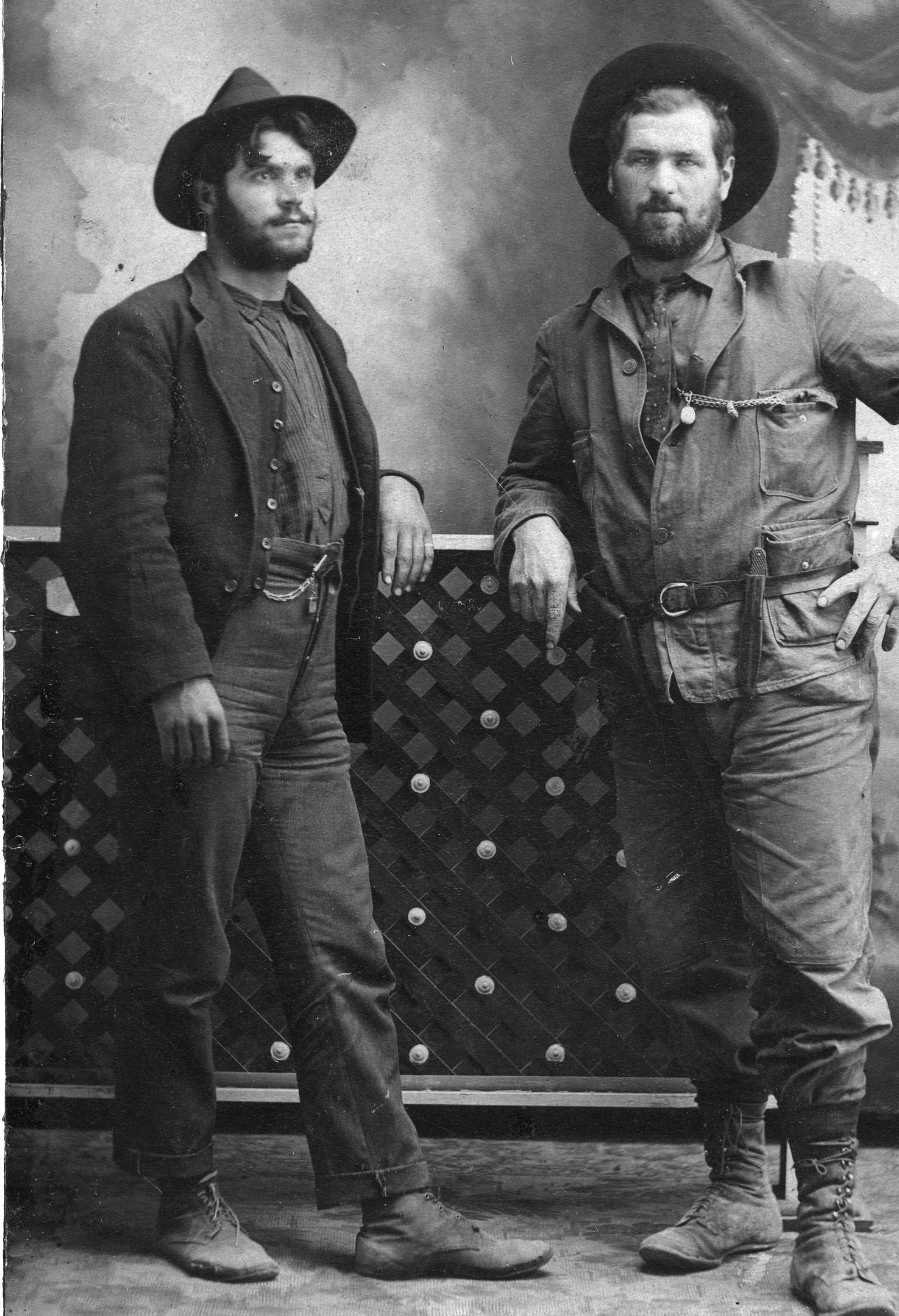

There is a story told about the discovery of the riches at Cobalt.

The myth of the hammer and fox is a great story, but it isnt true. There was no fox, and the discovery wasnt accidental. Larose found silver because he was a dedicated amateur prospector who spent his off-hours carefully studying the rocks along the rail line. Moreover, he wasnt even the first white person to discover silver in the region. Larose attempted to tell journalists what had really happened, but no one was interested. The story of the hammer and fox quickly became the preferred version, because the folk tale was a much easier and more compelling way to sell the image of a land so rich that a person could become a millionaire simply by accident.

The fact that a folk tale was used by journalists and businessmen to supplant the facts of the silver discovery might strike some as odd, but as H. V. Nelles writes: So remarkable were these discoveries in New Ontario that they could not be scaled by such mundane categories; they could only be measured in myths. But what do these settler myths say about the Indigenous people who were already here? The tale of the hammer and fox reinforces a much more troubling fiction of settlement that of terra nullius. Colonial claims in the Americas, Australia, and Africa were based on the dubious principle that the taking of Indigenous land was justified, not because the land was actually empty but because the original people were failing to use it according to European laws and custom. Thus, colonial narratives presented the Indigenous people as drifters or indolent or, in the case of Cobalt, unable to find wealth that was so obvious that it lay in pure form along the shores of Cobalt Lake.

In fact, a complex Indigenous silver mining trade in the region reached back thousands of years. Ceremonial panpipes made from Cobalt silver have been found in burial mounds in Ohio, Georgia, and Mississippi. Silver jewellery from Cobalt has been uncovered in archaeological digs in New York State. Nuggets of pure Cobalt silver were carefully placed in Michigan burial sites. Some of these burial mounds, known as Hopewell sites, are massive earthworks representing ingenious human endeavours that rival the construction of the great Egyptian pyramids. Who were the ancient Indigenous peoples who built these sites and traded in the beautiful Cobalt silver? It is not clear. Even the use of the term

Next page