Charles River Editors is a boutique digital publishing company, specializing in bringing history back to life with educational and engaging books on a wide range of topics. Keep up to date with our new and free offerings with this 5 second sign up on our weekly mailing list , and visit Our Kindle Author Page to see other recently published Kindle titles.

We make these books for you and always want to know our readers opinions, so we encourage you to leave reviews and look forward to publishing new and exciting titles each week.

Introduction

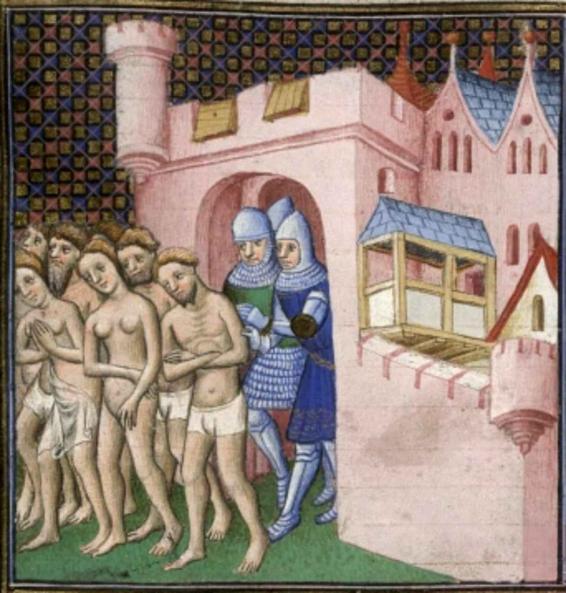

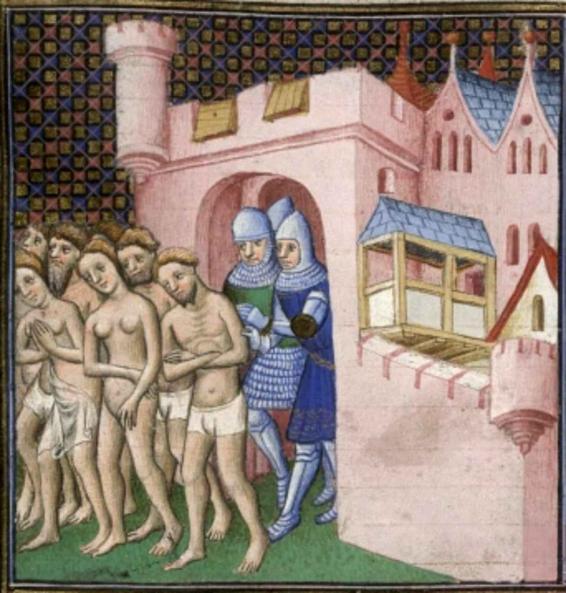

A medieval depiction of Cathars being expelled from Carcassonne in 1209

The Roman Church...[says] that the heretics they persecute are the church of wolves. But this is absurd, for the wolves have always pursued and killed the sheep, and today it would have to be the other way around for the sheep to be so mad as to bite, pursue, and kill the wolves, and for the wolves to be so patient as to let the sheep devour them! Excerpt from the alleged writings of the Cathars

The unique, copper-red hue of the naturally cracked earth on the foothills of the French Pyrenees is obviously stunning, but if the rumors are to be believed, they, too, are rich with medicinal properties. For centuries, locals have been scooping up and bottling the precious dirt and turning them into an array of poultices, salves, and even tonics.

This land is also home to several legends and local traditions. When the ground is drenched by heavy storms, the crumbling red soil drifts into the River Aude, staining the water with crimson. This beautiful, yet haunting phenomenon, which the locals call the blood of the Cathars, is a symbolic reminder of the blood shed by these heretics at the hands of the Catholic Church. Despite the controversial events, and their supposed heresy, it seemed that the fall of the Cathars brought an everlasting curse upon the region. As one unnamed farmer, documented by French medievalist Jean Duernoy, put it, Since the heretics were chased away from Sabartes, there is no longer good weather in this area. Another notary from Tarn echoed his sentiments, asserting, When the heretics lived in these lands, we did not have so many storms and lightning. Now that we are with Franciscans and Dominicans, the lightning strikes more frequently...

Christianity was not a state religion for its first three centuries, and it was only when Emperor Constantine the Great declared it so in the early 4 th century that the Church was faced with the thorny problem of state-sanctioned violence. The first major Christian authority to justify the use of arms in defense of Church and State was Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, who wrote in the 5 th century, They who have waged war in obedience to the divine command or in conformity with His laws, have represented in their persons the public justice or the wisdom of government, and in this capacity have put to death wicked men; such persons have by no means violated the commandment, Thou shalt not kill.

This opinion gained increasing influence in Western Christianity, though in the East, the attitude was (and continues to be) more nuanced. War was tolerated as a regrettable necessity in a world wounded by sin but never blessed. Canon law enacted in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire tended to treat soldiers who had killed as sinners needing to repent, and Bishop Basil of Caesarea (d. c. 330) believed that they needed to abstain from receiving communion for three years after battle. It was not that that the Eastern Roman Empire was a particularly peaceable statefar from it, in fact: it was engaged in almost continuous warfare for its entire existence. However, its conflicts were mostly defensive in character, fighting barbarians, Persians, or Muslims, and the idea of consecrating arms for the cause of Christianity was considered alien to its spirit.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5 th century, when Western Europe was governed by a Germanic warrior-caste, the theory of a just and virtuous war took root. The Roman Church enhanced its authority by sanctifying oaths taken for just military purposes, and Bishop Anselm of Lucca (d. 1086) was the first to suggest that military action for the cause of religion could remit sin. At the Council of Clermont in July 1095, Pope Urban II canonized religious war by urging Western Europe's nobility to take up arms in defense of the Byzantine Empire against the Muslims, thus launching the Crusades. Religious military orders such as the Knights of Saint John, the Templars, and the Hospitallers arose, ostensibly founded to protect the weak and the sick but also to extend the boundaries of Christianity and the power of the Church. In Europe, the knight, originally a mounted warrior, became a consecrated soldier of Christ, dedicated to the defense of the Church by solemn vows made before an altar.

It was not long before the concept of the holy crusade was applied beyond the holy land. The conflict between the Christian states and the Muslim Moors in the Iberian Peninsula became a holy war, as did the forced settlement of Pagan Slav lands on Germany's eastern frontier. At the beginning of the 13 th century, the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights of Livonia began the conquest of heathen Baltic lands while Sweden invaded Finland.

Naturally, the question remained concerning the use of arms against other Christians. Eastern Christians did not acknowledge the Pope's supremacy, and many held that it was lawful for him to declare a crusade to bring schismatics back to the obedience of Rome. German knights fighting the Orthodox Russians at the Battle on the Ice in 1242 believed this, as did the Hungarian prosecutors of the 1235 invasion of Bosnia, which was thinly disguised as a crusade. The Church even extended the object of crusade to believers in communion with Rome, who refused to obey lawful authority. After peasants revolted against the Prince-Archbishop of Bremen in 1204 over tithes and land rights, Pope Gregory IX was persuaded to declare them heretics and proclaim a crusade against them, and when the heresy of Catharism began to take root in southeastern France toward the end of the 12 th century, both Church and State considered the use of force to extirpate it.

The 15 th century was a pivotal era for Europe, during which it transitioned from a social and religious union under Christendom into a disparate collection of nation-states, and it was during this period that the Middle Ages came to an end and the Modern Period began.

Less than a century earlier, in the mid-14th century, the Vatican called upon England and sought financial aid in the hopes of boosting papal defenses against French forces. It was then that John Wycliffe boldly stepped forth and appealed to the John of Gaunt, urging the Duke of Lancaster and Parliament to repudiate Rome's demands and citing what he believed to be the Church's abundance in wealth. According to Wycliffe, Christ's disciples, particularly clergymen, must aspire to live modestly and shun all material pleasures. Such was the word of the Lord.