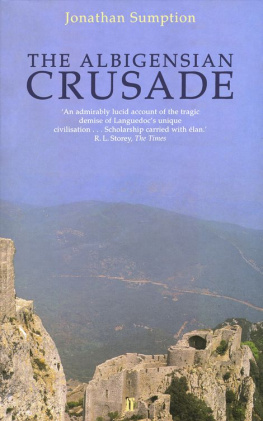

THE ALBIGENSIAN CRUSADE

THE ALBIGENSIAN CRUSADE

AUBREY BURL

First published in 2013

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Aubrey Burl, 2013

The right of Aubrey Burl to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9479 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to many people for their guidance and assistance in the writing of this book: to Janet Shirley for her translation of the Chanson de la Croisade; Mervyn and Gunilla Elliott for the luxury of their gite in a vineyard near Limoux; Richard Parsons-Jones of Tanners Wine Merchants, Shrewsbury, for his information about the history of wine-growing in the south of France; Mme Andre Cancel of Lavaur for her generous provision of historical material about the town; and the two ladies who did the same for Muret; Rosemary Baker for her discovery of two elusive articles; and Michael Costen for his warnings about driving along the backroads of the Languedoc with insufficient petrol and, also, for the equal warning of the challenge of Montsgur.

I am also very grateful to the staff of Sutton Publishing, in particular to Catriona Belk, Sarah Flight and my editor, Christopher Feeney, for their sensitive repairs to an ailing typescript. And, as always, this book owes much to my wife, Judith, who despite her enthusiasm for open-air markets was always happy to endure a climb to yet another ruinous castle in the clouds.

On our wanderings in search of the barbarities and tragedies in the towns and villages of Occitania the only mutilation we inflicted was slight, some minor misuses of the lovely French language.

DEDICATION

To the schoolmasters and lecturers who taught me that history is about men and women

The Cathars believe that there are two gods. One is good and a saviour, the Father of good spirits, in which they believe. The other created the world and human beings, and they have no faith in him. The Father of spirits was light. The creator of the world was, for them, the Prince of darkness.

Evrard de Bthune, twelfth century Liber Anti-heresis.

Preface

T his is a book about an agonising tragedy. Worse, the tragedy endured over lifetimes in one of the loveliest regions of France. The medieval story of the region is like a cleverly crafted mosaic, attractively coloured and patterned but out of it, if one stares with intensity, the image of a devils face emerges.

The region of the Languedoc, literally, the language of Occitania, is four hundred miles from Paris in the deep south-east of France. It is a world of its own. To the south are the Pyrenees with their snows and alpine meadows. Below them are expanses of limestone plateaux, causses, some transformed for the grazing of cattle, others harshly wild with infertile soils.

On the lower plains, Languedoc is a quiet countryside of quiet rivers, the Garonne, Tarn, Hrault, and of noisy cities: Albi at the north, that gave its name to the crusade; Toulouse to the west that was besieged three times; Carcassonne at the centre; Bziers in the east, that suffered the first insanity of slaughter.

In the north are the Aubrac mountain roads with their lines of winter poplars like the upturned broomsticks of witches. In the south, jagged ravines writhe through the landscape, like the fantastic otherworld of the precipitous Gorges de Galamus above St Paul de Fenouillet, where the narrow, twisting, rock-hung road is a triumph of French engineering. At the rich heart of Languedoc are the vineyards of the Corbires, wind-blown Minervois and Roussillon. The entire region is an idlers paradise.

There are architectural wonders: the late eleventh century cloisters at Moissac, the delicate traceries of the pink marble tribune-cum-choir at Serrabone. The visitor needs to absorb the half-timbered romance of the square at Mirepoix and wander around circular bastides, like Montauban, with their chessboard-planned streets. To these pleasures can be added explorations of the old quarters of Toulouse with their glow of golden-red brick; a tour of the sombrely reconstructed parapets and ramparts of Carcassonne; and sight of the awesome dominance of the recently completed St.-Just cathedral in Narbonne. There are also the literally breathtaking ruins of castles on the crest of steeply approached mountains: Roquefixade, Quribus, Montsgur among them.

Occitania is a vast area, a pentagon like the gable end of a house of some 30,000 square miles with Gueret at its apex, the roof sloping down to Bordeaux at the west and the Rhne at the east, and the bottoms of the walls at Auch and Narbonne.

Languedoc, langue doc, was the part of southern France where a Latin-based Romance language was spoken. The langue dOl in northern France used oui as a corruption of the Latin hoc ille meaning yes. Closer to the Latin was the oc of Occitania. Even today the region has a dialect of its own, understandably partly Spanish with that country only forty miles away across the mountains. The speech is a little like Catalan. The price of cushions in the open-air Sunday market of Espraza near Limoux sounded like only five francs but was actually a hundred; the French sahn for cent became sang in the local patois. The s is soft, consonants hard so Lauragais is low-rag-ace. No one speaks pure Occitan today, but it is preserved in the literature of the Languedoc and in the accents of local people.

The Languedoc is a visitors wonderland. But it is also a land of blood. It is not the great cities with their traffic and their crowds that so starkly evoke the pain and the tragedies. It is the small town, the village: the courtyard of Villerouge-Termens castle, where a pyre of straw and vine-leaves burned an unbeliever to death; the broken walls of the well under the cliffs at Minerve, overlooked today by a replica of the trebuchet that smashed and shattered the covered path descending to that vital source of water; the immense cavern at Lombrives, where steps and ramps trudge uneasily up to an inner gallery in which, it is said, seven centuries ago, fellow Christians walled up the faithful to die of starvation. Perhaps the saddest, because so simple, is the memorial stone at the edge of Lavaur where Guirauda, the deeply-loved chtelaine of that fortified town, was savagely murdered. These are the places where the grim memories of the Albigensian Crusade most grievously survive.

The horror began in 1209 when the Catholic Pope, Innocent III, ordered a crusade against the obstinate heretics known to outsiders as Cathars, the pure ones. They believed in two gods, one spiritual and Good, the other earthly and Evil, and denied the physical reality of the Crucifixion. The Catholic church pronounced an anathema, demanding the extermination of the ungodly.