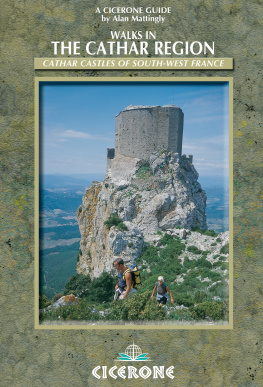

To the Languedoc and its castles,

from Aguilar to Usson,

in whose courts the troubadours sang.

Hard walking up the steep unpaved tracks

But the empty halls serenade an unforgotten past,

whether Miraval, Saissac or Tuchan,

or, most of all,

Puivert whose musicians still look down today.

Surely the greatest glory of Occitanian civilisation that which made it known throughout Europe was the troubadours. They started writing their lyrics around the time of the First Crusade (1095) and continued even through the period of catastrophe and decadence until about 1295

(A. Bonner, Songs of the Troubadours, 1973, 14)

There are many people to be thanked for their help in the writing of this book: Sarah Bond for Brownings good poem about Jaufr Rudel; Arthur Brown of Ash Bank Photography for the pictures of Burlats and Die; Peter Dale for his translations of Dante and Villon, and his reminder of Swinburnes better poem about Rudel; Aurlie Friedel (Lilet) for the photograph of the statuette of the countess among the commemorative fountains at Die; Peter Meadows for details about Byrthnoth, the Battle of Maldon and the memorial in Ely Cathedral; to Michelle and colleagues at Jessops Photography for their diligent preservation of a damaged film; and to Arthur Brown for restoring the images, and to the Information Office at Tamworth for guidance to the statue of Ethelfleda near the castle.

Birmingham University Library and the Society of Antiquaries of London assisted with background material, as did numerous custodians of courts and castles throughout the Languedoc.

The writing of this musical-cum-martial history was greatly eased by the advice and encouragement of Jim Crawley, Sarah Flight, Hilary Walford and Mary Critchley of Sutton Publishing at a time of considerable change for them.

As always, my thanks go to Judith, my wife, who accompanied me on explorations in Languedoc and elsewhere and encouraged me to search for elusive compact discs of troubadours and trobairitz, even long-forgotten trovres, discs lurking in diverse places like the Muse du Moyen ge in Paris; and the souvenir shops of widespread French abbeys and cathedrals.

And finally, of course, my gratitude and appreciation goes to those melodious singers of long ago. Their songs can still be heard. Faintly.

Contents

Appendices |

One |

Two |

Three |

Four |

Troubadours: Language: French, Occitan and Obscene!

They were all different. I shall write a song about nothing at all, laughed Guilhem of Poitiers. I am heartbreakingly in love with a far-off woman, pined Jaufr Rudel, although I have never seen her. Some troubadours sang of loves joy, others of its pains. Others not of love at all. I chant of battles, blood and booty, proclaimed Bertran de Born. More romantically, some serenaded their hostess, occasionally too persuasively for the dangerous jealousy of her husband. They were all different, even the women troubadours, the trobairitz.

One woman grieved at laws that forbade her to wear vel ni banda (pretty veil or silken wimple). Another mourned that her lover had abandoned her

car ieu non li dormei mamor

because I would not sleep with him.

For two and a half centuries in the south of France fine courts and castles enjoyed the music of the troubadours as they entertained audiences in the medieval age of chivalry.

Chivalry did not always mean chastity. It is a general belief, but a mistaken one, that troubadours sang of pure, courtly love, a dispassionate belief in honourably polite behaviour by men towards the woman that they adored, a remote and unattainable goddess.

Such a platonic ideal was both extolled and frequently disregarded. Troubadours, whether nobly born or commoner, had the natural urges of later poets such as the Elizabethan Christopher Marlowe when he translated an elegy of Ovid:

I clingd her naked body, down she fell,

Judge you the rest: being tird she bade me kiss;

Just send me more such afternoons as this.

(Ovid, Elegy V, 246, Lying with Corinna, 246)

A few years later John Donne wrote:

Full nakedness, all joys are due to thee,

As souls unbodied, bodies unclothed must be.

(Elegy XIX, To His Mistress going to Bed, 334)

But four centuries earlier the troubadour Arnaut Daniel had sung:

Del cors li fos non de larma

Would I were hers in body, not in soul!

And that she lets me, secretly, into her bedroom.

(Lo ferm voler The Firm Desire, 1314)

The passion is there, but it is not coarse. It may not be chaste, but it is respectful, and this is true whether of French-writing trouvres of northern France or of troubadours composing in the langue dOc of the south. Exceptions to their seemliness are few.

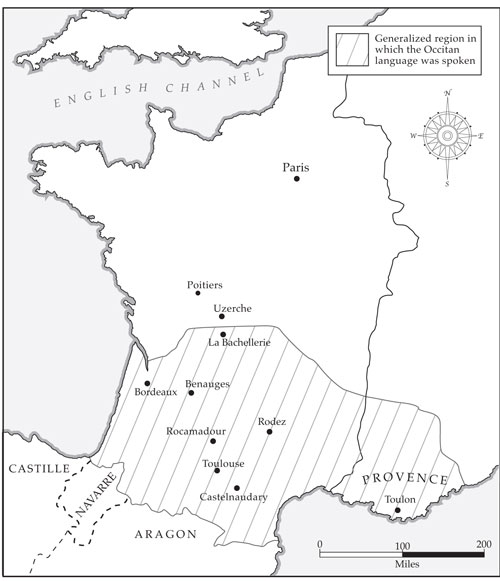

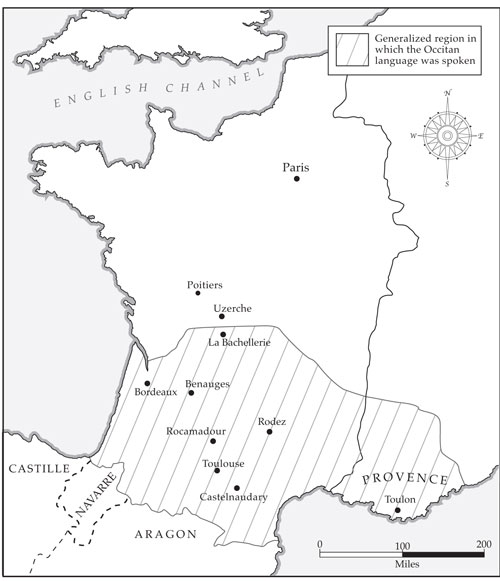

Most troubadours composed their songs and poems in the Romance language of Occitan in southern France (Fig. 1). It was similar to French, but there were differences, sometimes considerable, of vocabulary and spelling. In this book the custom is to quote short extracts, often one line, from the original Oc followed by a full translation in English.1

For readers wishing to hear modern renderings of the medieval words and music, Appendix One lists compact discs of troubadour music known to the author. It also contains the names and songs of the individual musicians.

Despite the above protestations of respectful wording in this book, there must be a warning for readers offended by obscenities: Chapter Four contains profanities, some so socially unacceptable that neither their modern forms nor their classical roots are included in the majority of dictionaries, whether English or Latin.

The justification for the inclusion of such language is that the subject of that chapter, the earliest-known troubadour, Guilhem, 9th Duke of Aquitaine and 7th Count of Poitiers, intentionally used it to avoid ambiguity about his meaning. The expletives were, however, infrequent, occurring in only two of his eleven surviving songs.

As noticed above, later troubadours frequently shared his amorous enthusiasms but expressed them in terms that would have been entirely acceptable to a Victorian afternoon tea party.

A note has to be added about the names of troubadours. In an age when literacy was uncommon, when there was no standardisation of language and when local dialects were prevalent, much spelling was phonetic and inconsistent.

As an example, one singer had a surname variously spelled: Mareuil, Marolh, Maruelh, Marueill, Marvoil and five more alternatives. To avoid such contradictions names here generally follow todays French translation of the original Vida, the biographical Life, written by medieval chroniclers.

In their 1973 Biographies des Troubadours, the editors, Boutire and Schutz, updated the old Occitanian rnaut de Maroill to the now-accepted Arnaut de Mareuil. Similarly, Savaric de Malleo of Chapter One became Savaric de Maulon; and the Duke of Aquitaine and the Count of Poitiers of Chapter Four, once recorded as Guilhem, lo Coms de Peitieus, is now Guilhelm of Poitiers.

Map 1. Regions of the Occitan language.

Next page