Troubadour's Song

The Capture, Imprisonment and Ransom ofRichard the Lionheart

DAVID BOYLE

Copyright 2005 by David Boyle

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission

in writing from the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 2005 by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc. Originally published in

Great Britain in 2005 by Penguin.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Walker & Company,

104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is

available from the Library of Congress

eISBN 978-0-802-71820-4

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For Robin

born 15 July 2004

Contents

Section One

1. Three generations of English kings: Henry II, Richard I, Henry III and John.

(clockwisefrom top left)

Section Two

Illustration Acknowledgements

1 British Library, London. MS Cotton Claudius D. VI, fol. 9V. Photograph AKG-images, London; 2 Bibliothque Nationale, MS Fr 854, fol. 230; 3 Pierpont Morgan Library, New York/Art Resource; 4 British Library, London/The Art Archive; 5 British Library, London. MS Roy 2A XXII, fol. 220; 6 Chetham's Library, Manchester. Photograph Bridgeman Art Library; 7 Bibliothque Nationale, Paris, MS NAL 1390, fol. 57V; 8 Giraudon Picture Agency, Paris; 9 Conway Library, London; 10 British Library, London. MS Royal 16 G VI, fol. 35OV. Photograph AKG-images, London; 11 Muse du Chteau de Versailles. Photograph RMN/Gerard Blot; 12 Private Collection. Photograph Bridge-man Art Library/Ken Welsh; 13 Austrian National Library, Vienna; 14 Burgherbibliothek, Bern. Cod. 120 II, fol, 129r. Photograph AKG-images, London; 15 from Drnstein, Edition Gottfried Rennhofer, Korneuburg, Austria; 16 Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; 17 Manchester City Art Gallery; 18 Museum in Schottenstift, Vienna; 19 British Library, London. Miscellaneous Chronicle, MS Cotton Vit. A XIII, fol. 5. Photograph AKG-images, London; 20 Archiv fr Kunst und Geschichte; 21 From John Gillingham, Richard 1 (Yale, 1999); 22 Bibliothque Nationale, Paris. Nouv. Acq. Fr. 1050, fol. 77V; 23 British Museum, London. MS Royal 14C VIII; 24 Archivo Iconografico, SA/Corbis; 25 Photograph Museum of London/HIP; 26 Photograph by Stefan Drechsel/AKG-images, London; 27 From Charles Knight, Old England:A Museum of Popular Antiquities, Vol. 1, c. 1860; 28 Photograph Amelot/AKG-images, London; 29 Illustration by Helen Stratton from Agnes Grozier Herbertson, Heroic Legends (London, 1911); 30 Nottingham City Museums and Galleries (Nottingham Castle). Photograph Bridgeman Art Library.

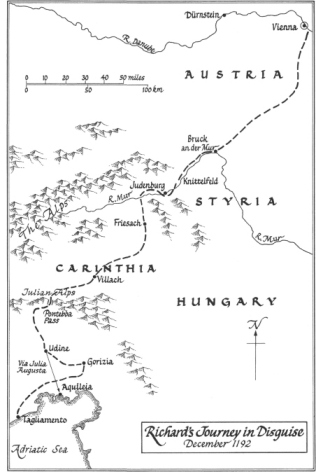

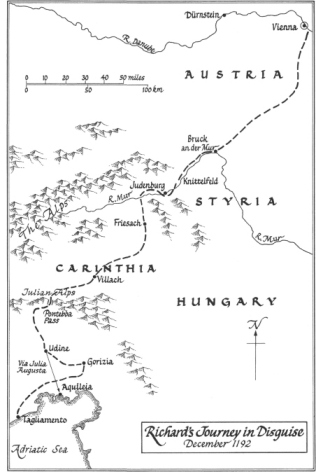

Three encounters shaped the process of writing this book for me. The first was clambering up, on what seemed the hottest day of my life, to the ruins of Diirnstein Castle in Austria the traditional spot for the legend of Blondel's song and gazing down on the sloping vineyards and the Danube snaking along below. The second was sitting in candlelight during the atmospheric annual Advent service in Salisbury Cathedral, next to the tomb of William Longspee, the last of Richard the Lionheart's brothers to die, and imagining the scene of his funeral. And the third was in Vienna, while I was researching the book. I told one very helpful historian that I was writing about Richard's imprisonment. 'Ah!' he said. 'You are writing a children's book?' It was confirmation of what I had begun to suspect, that for some reason and probably the legend of Blondel as much as anything else the story of Richard's bizarre journey in disguise, his disappearance and his imprisonment has been relegated by serious historians to children's books and romantic novels. It made me all the more determined to write about it.

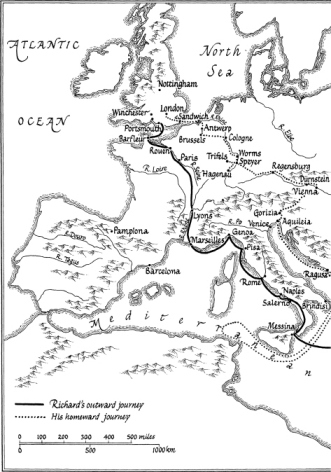

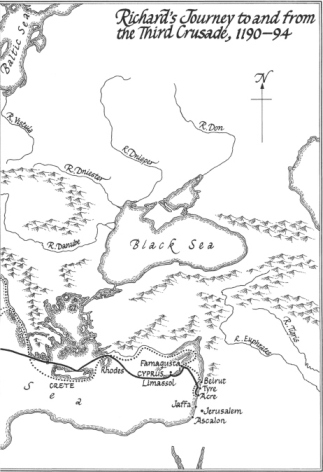

There is another reason for their reticence, of course. Although there is considerable evidence about Richard's ransom and homecoming, the chronicles give only the sketchiest details about his journey and arrest, and what evidence there is tends to be contra-dietary. But in the course of my research, I have found that, by retracing the critical parts of the journey, and sifting the local traditions that do not actually contradict each other, it is possible to build a convincing picture of what took place. It may not be definitive throughout and parts of it may not be absolutely certain though little is certain in medieval history but you have only to stand on the castle walls at Gorizia in Italy in winter and stare at the icy mountain wall that seems to block any progress to theeast to have an overwhelming sense of which way Richard and his companions fled.

This book is an attempt to weave together that sort of geographical evidence with local traditions from the route that Richard travelled in 1192 and information from the reliable chronicles some of them based on eyewitness accounts that we do possess. It is intended as a popular history, so I have tried not to interrupt the story too much with detailed argument about which legend or chronicle to believe, though some of the sources I have used are outlined in the notes at the back of the book. Throughout the process of researching the story, I have also found myself returning over and over again to the work of three medieval historians in particular. One is John Gillingham, whose dedication to the details of the life and world of King Richard has done so much to dust down his reputation, both as a king and as a military strategist. The second is Christopher Page, whose scholarship has managed to fill in so many gaps in the story of the development of twelfth-century music. The other is my godfather, Peter Spufford, whose pioneering work on medieval money and in