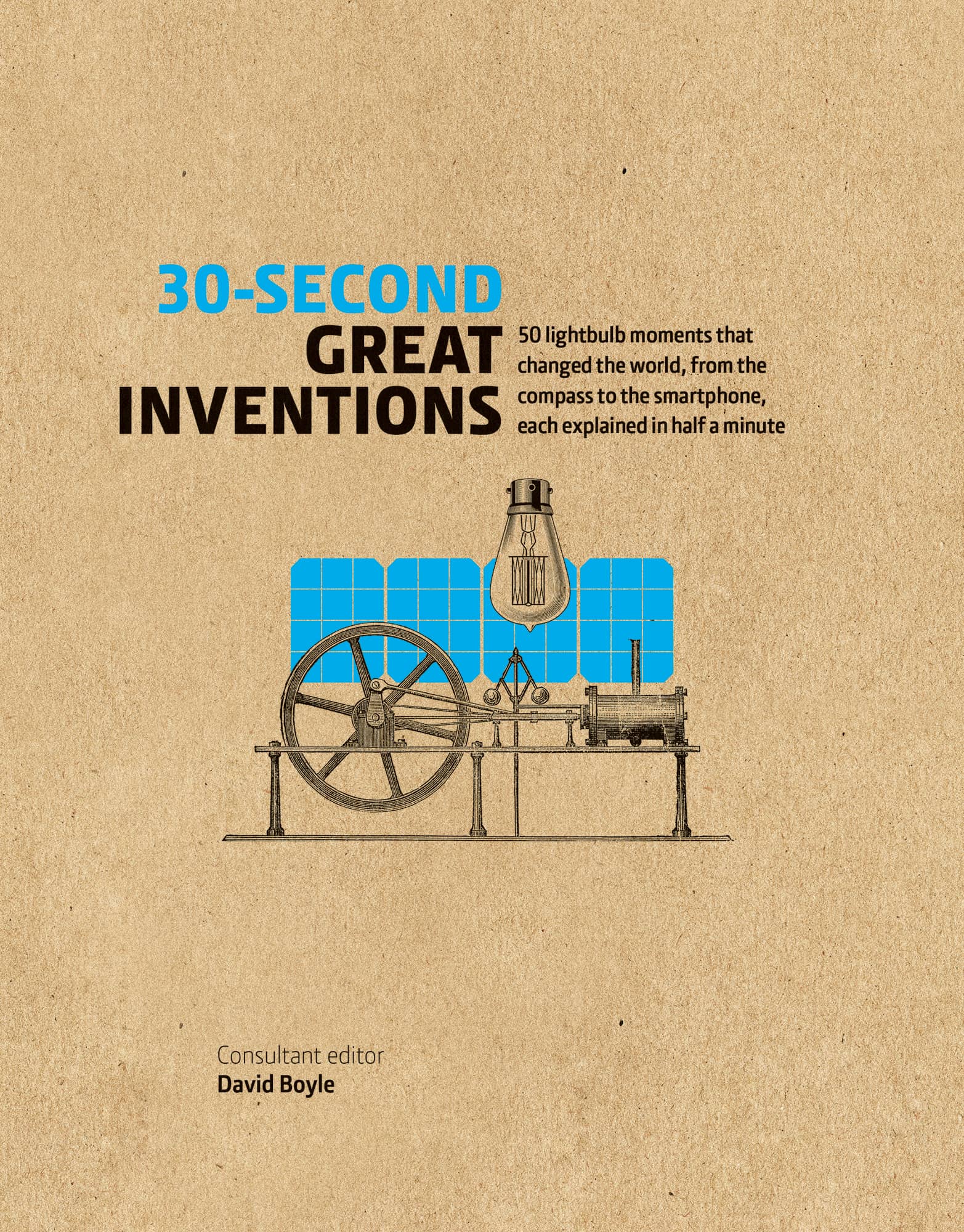

30-SECOND

GREAT INVENTIONS

50 light-bulb moments that changed the world, from the compass to the smartphone, each explained in half a minute

Editor

David Boyle

Contributors

David Boyle

Judith Hodge

Diana Rawlinson

Andrew Simms

Illustrations

Steve Rawlings

First published in the UK in 2018 by

Ivy Press

An imprint of The Quarto Group

The Old Brewery, 6 Blundell Street

London N7 9BH, United Kingdom

T (0)20 7700 6700 F (0)20 7700 8066

www.QuartoKnows.com

2018 Quarto Publishing plc

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage-and- retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Digital edition: 978-1-78240-684-6

Hardcover edition: 978-1-78240-512-2

This book was conceived, designed and produced by

Ivy Press

58 West Street, Brighton BN1 2RA, UK

Publisher Susan Kelly

Creative Director Michael Whitehead

Editorial Director Tom Kitch

Art Director James Lawrence

Project Editors Fleur Jones, Stephanie Evans

Designer Ginny Zeal

Assistant Editor Jenny Campbell

INTRODUCTION

David Boyle

What makes a successful inventor? There are many ingredients. You need to have the background knowledge in your field like the Wright Brothers, American pioneers of the aeroplane. You need to know the right people who can help you exploit your invention, as Scottish engineer James Watt did when he famously got together with Birmingham manufacturer Matthew Boulton to make the most of Watts improvements to the steam engine. Then you need people to understand the significance of what you have created; without this an invention can lie ignored and unexploited for decades, as Scottish inventor James Blyth found with his wind energy machine. You also need to have investors and you need to be able to protect your invention, as the rival inventors of the pneumatic tyre, Robert Thomson and John Boyd Dunlop, discovered. But most of all, you need a moment of inspiration.

Sometimes this is a revelation that is then worked out carefully in theory, as with Archimedes screw, an ancient Greek invention. Sometimes it is a series of exhausting experiments to see how the theory works in practice, which might take years, as English engineer Frank Whittle found developing his jet engine. Or it appears, as the pioneering English economist John Maynard Keynes described, like a grey woolly monster in my head.

When you look at a range of different inventions and inventors, as you can do side by side in this book, it becomes clear that to be successful inventions also have to come along at the right moment. Of course, as with any rule, there are exceptions to this. The mechanical clock, invented by the Chinese in the eighth century, failed to spread to the rest of the world until the twelfth century; the use of paper money, pioneered by Mongol ruler Kublai Khan in the twelfth century, did not reach Europe until the end of the seventeenth century. But generally speaking, successful inventions hit the spot because they are developed at a time when there is both the knowledge to make them possible and a need they can meet. This was true of Watts steam engine and also of the steam boat, plastic and the internal combustion engine.

This raises an important question. Were the inventors of these things the only people who could have made the breakthrough they did? Or did they happen to be in the right place at the right time so they could steal a few years or days on their competitors? If Watt had died young or become caught up in the aftermath of the efforts of Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) to regain the throne in 1745, and never ended up as a student in Glasgow, nor met his friend the physicist John Robison, or the other doyens of the Scottish Enlightenment, would somebody else have made the breakthrough he did with steam power?

It is impossible to be sure. But lets keep a place for the role of individual genius. The inventors in this book are all people who managed to understand their field so completely that they were able to see what else, which new development was possible. Yet at the same time, they brought some insight from outside the field to bear on the problem. American inventor Thomas Edison famously claimed that invention was 1 per cent inspiration and 99 per cent perspiration, and he went on to prove it in his tireless search for the right material to maximize the brightness and longevity of the filament in his light bulb. He had more than 1,000 patents to his name, so he may have proved this point but there are other examples to the contrary. Nor do many people really believe that they might be an Edison if they just put in enough perspiration. No, moments of inspiration are vital, too: progress is underpinned, whether it is in technology, economics or social development, by moments of personal imagination.

In addition to all this inventions need wider networks of people to make the breakthrough idea a reality. They need connections with people powerful or wealthy enough to make change happen. This may explain why so many inventors are white men, because those critical networks may not have been available to anyone else. 30-Second Great Inventions includes two brilliant twentieth-century women inventors. There must be many more whose graves are not marked and whose memories are not celebrated.

How this book works

There are seven sections, designed to include as much of the science, technology and economics of inventions as possible. The first section looks at Materials, from cement through to petroleum and plastic. Construction & Engineering investigates key mechanical breakthroughs such as the mechanized clock, the internal combustion engine and the plough. In Transport & Location, we cover inventions connected to movement, from the pneumatic tyre to GPS satellite positioning. Medicine & Health probes the medical field, from antibiotics to pacemakers. Communications runs the gamut from the printing press to the smartphone including, of course, Tim Berners-Lee and the Internet. Economics & Energy looks at everything from credit cards to solar energy. Finally, Daily Life highlights those inventions that many people now take for granted, from heating and lighting our homes to preserving food by canning and refrigeration.

Each entry in this book is accompanied by a pithy 3-second survey, which boils the facts down to the absolute basics. There is also a 3-minute overview, which tries to give a different and more challenging edge to the story, together with biographical facts for the key players.