Patent applications to be processed at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C.

Preface By Trevor Baylis, OBE, inventor

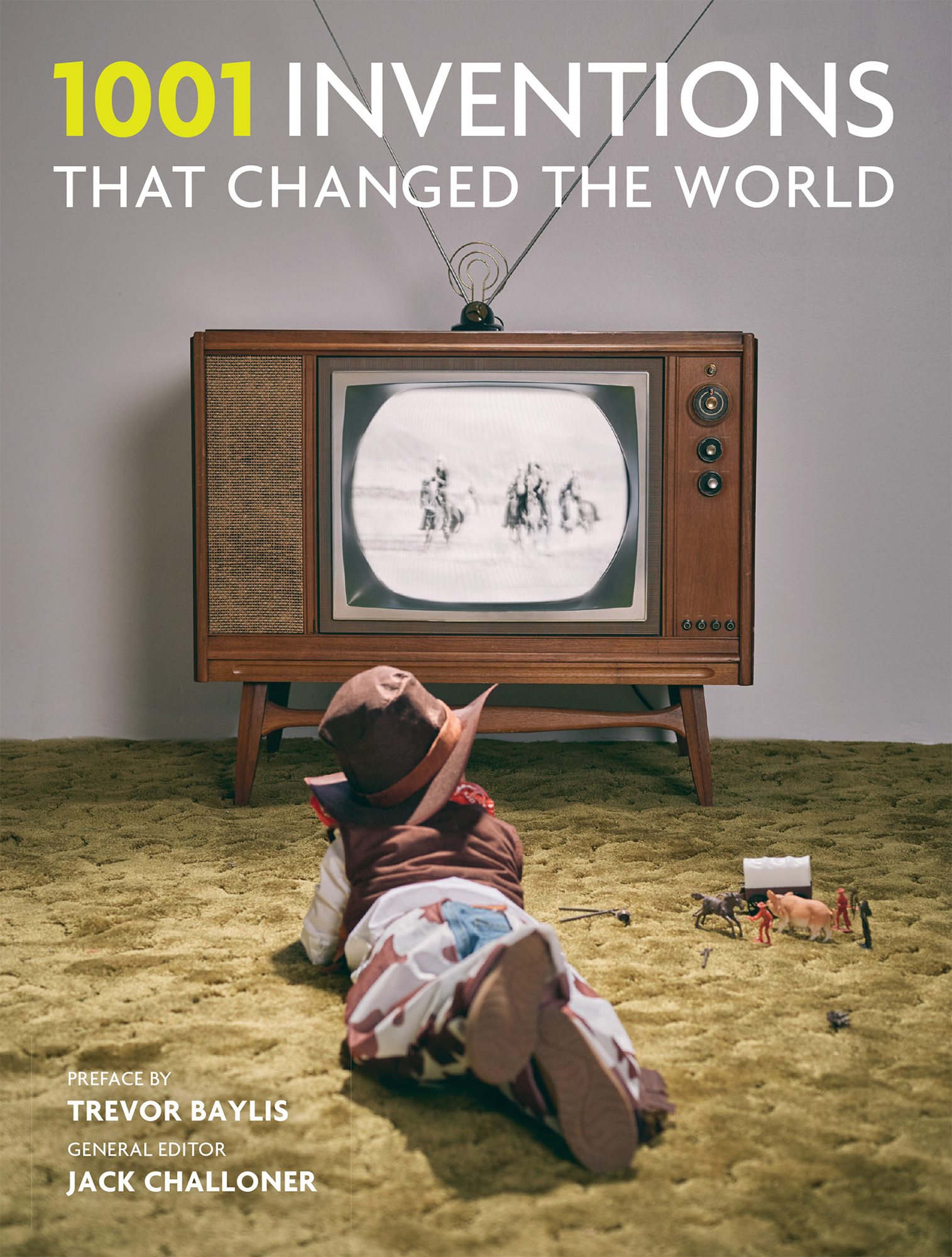

If you run your eyes down the list of inventions in this book, you will be amazed that many everyday items are a lot older than you thought they were. The fishhook, for instance, first appeared 35,000 years ago, while computer programs were developed as early as 1843. And I believe there is such an invention in all of us. How many of us have a great idea but do nothing about it, assuming it has been thought of before, only to realize months or even years later that if you had got off your backside and done something about it, you could have been listed in this book.

I also believe in the great inventor Louis Pasteurs tenet that chance favors the prepared mind. In fact, it was purely by chance that I was watching a television program about the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa one night. I was appalled when I saw naked bodies being thrown into open graves. The reporter said that the only way to control this epidemic effectively was by spreading health information and education through radio broadcasts. But there was a problem: most of Africa is without electricity, while batteries are unaffordable for many. Watching the program, I suddenly pictured myself in colonial times, wearing a pith helmet and monocle with a gin and tonic in my hand, listening to my large wind-up gramophone with His Masters Voice records blaring out of a large horn on top of a turntable. It instantly occurred to me that if you can get all that sound by dragging a needle around a piece of Bakelite, then surely there is enough power in the spring to drive a small dynamo which in turn could drive a radio. This was my Eureka! moment on the way towards developing the clockwork radio, and the rest went like, well, clockwork.

This story serves to illustrate that many inventionslike soap, the flushing toilet, scissors, or the fountain penare inspired responses to perceived needs. Yet, ironically, it is often something dramatic like war that motivates individuals to produce weapons like rockets, before people find uses for them that benefit mankind in a more agreeable way.

But once youve had that big idea, how many of us know what to do next? Remember: a picture is worth a thousand wordsbut a prototype is worth millions! Alas, many people dont know that if you go down to the pub and tell everyone about your idea, you cannot protect it legally any longer. The keyword is intellectual property because nobody pays you for a good idea, but they might pay you for a piece of paper (like a patent, design registration, or copyright document) that says you own the idea. Luckily, I knew about intellectual property when I invented the clockwork radio. But I still had to rely on the Patent Office to tell me that I should consult a patent attorney. (I like to think that thats because lawyers are the only people who can write without punctuationsomething I never learned at school.)

Hence, I think its about time for us to take inventors more seriously. Perhaps we should make the process of invention part of the National Curriculum, so when someone comes up with a good idea, they will know what steps to take to protect it, and how to get the product to the market. One of my favorite expressions is Art is pleasure, invention is treasure, and when you look at the list of these 1,001 inventions you realize how many of them are vital to our everyday life. Moreover, inventions are crucial to the continuing growth of industry and commerce, and inventors like Frank Whittlewhose company built the first jet engine in 1937, the year I was bornhave ensured that our previously gigantic planet has become a global village that none of our forefathers could have ever imagined.

I must congratulate the contributors of this book for compiling such an interesting and thought-provoking list of inventions. The collection invites reflection on what is important to us in our daily lives, and it is also very entertaining. The book celebrates how ordinary men and women have changed our livesboth socially and commerciallywith their knowledge and creativity, and the later section in particular provides ample evidence of how quickly our inventors change the world.

Trevor Baylis, London

Introduction By Jack Challoner, General Editor

To invent is to create something newsomething that did not exist before. An invention can be an idea, a principle (such as democracy), a poem, a dance, or a piece of music, but in this book we have restricted ourselves to technological inventions. Technology is the practical application of our understanding of the world to achieve the things we need or want to do. Technology goes beyond things such as computers or bicycles: it includes techniques and processes, such as the alphabet, numerical systems, and the extraction of metals from their ores.

Scientific theories and discoveries are not included in this book. Science is our way of unraveling the laws of nature through theory and experiment. Science and technology are interdependent. The internal combustion engine, for example, could not have been invented without a scientific understanding of thermodynamics and the chemistry of combustion. Conversely, inventions such as the microscope, the radio telescope, and the computer have greatly aided scientific investigation.

When I began to compile this books list of inventions, I wondered whether 1,001 would be too many. But I soon realized that countless technological innovations, large and small, have played roles in defining the way we live. Every one of the inventions in this book has changed the world in some way, but so have many others that I had to leave out.

So how did I decide upon the final list? I knew that readers would pick up the book to discover who invented the paper clip, the nonstick pan, or scissorsthus, the index contains virtually any invention of that kind. This inevitably led to a bias toward modern inventions, although the increasing pace of technological innovation dictated that this always would be the case. I also wanted the book to introduce important but less well-known technologies. You will find these by browsing or by following cross-referencesor by chancing upon intriguing and eye-catching images.

1001 Inventions That Changed the World is ordered chronologically. However, there is not always a definitive date for the first appearance of an invention. The incandescent light bulb, for example, developed gradually over the entire nineteenth century. Rubber was first vulcanized in ancient Mesopotamia, but it was not really used until much later. So, for the light bulb, we have given the date of the first working incandescent bulb in a form we would recognize today; for vulcanized rubber, we cited the date of the introduction of the modern industrial process. For ancient technologies where no record exists of who invented them or when, we have based the dates on the oldest existing evidence or on other best guesses.