POPULAR

SCIENCE

INVENTIONS

THAT CHANGED

THE WORLD

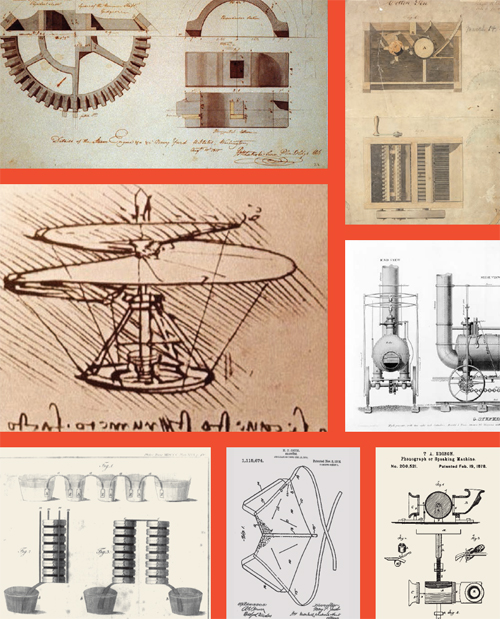

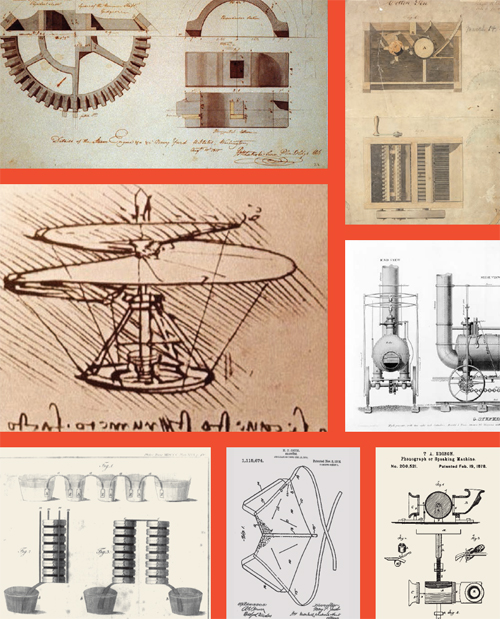

Great inventions can come about by accidenta burst of information or slow, plodding experimentationbut all at some point must be fleshed out on paper if the promise of their potential is to be fulfilled and duplicated for the future. Examples of some of those drawings include (clockwise from top left) Watts steam engine, Whitneys cotton gin, Stephensons locomotive engine, Edisons phonograph, Jacobs brassiere, Voltas battery, and da Vincis helicopter.

Introduction

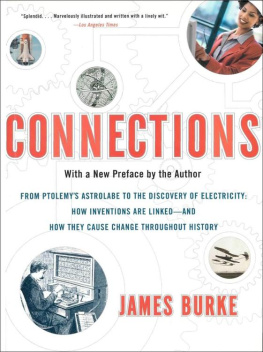

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple and one of the greatest innovators of our time, once said, Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didnt really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. Thats because they were able to connect experiences theyve had and synthesize new things.

J obs knew what he was talking about. Historys greatest innovators stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Using discoveries that were hard-won or accidentally uncovered, inventors have changed the way we live by working passionately to connect the dots and make sense of the world around us.

Today, the modern men and women of innovation continue to analyze past technology in pursuit of the advancements that will define our future. Where will computers go from here? How can we leverage progress with the needs of an increasingly globalized community, and what will trigger the next medical breakthrough? These and many more unanswered questions continue to inspire some of the greatest minds of our time.

The inventions on the following pages illustrate the courage, resilience, and innovation of the human spirit, while simultaneously suggesting the challenges that remain. Perhaps, most importantly, the advancements listed here also demonstrate how a single spark of brilliance can touch us all. Writer William Arthur Ward once said, If you can imagine it, you can achieve it. All these inventions began in someones imagination, but it is their achievement that truly changed the world.

Chapter 1

The Stuff of Science

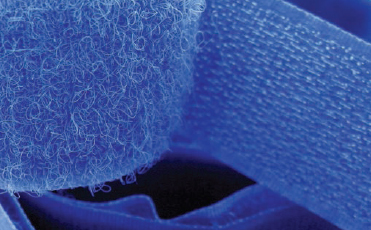

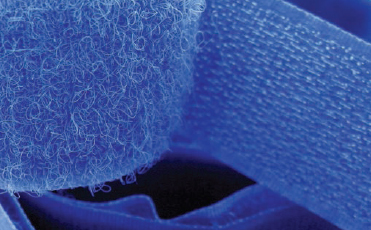

A closeup shot of Velcros loops (left) and hooks (right).

Velcro

Many artificial objects were inspired by something organic or found in nature. Velcro, sometimes called the zipperless zipper, is one of those items, modeled after the common seed case of a plant.

V elcro consists of two surfaces: one made up of tiny hooks and the other composed of tiny loops. When the two sides are pressed together, the hundreds of hooks latch onto the tiny loops, producing a firm binding that is easy to undo by pulling on the top surface, making a familiar rasping sound. Today Velcro is used in hundreds of products, from coats to childrens shoes, blood pressure gauges to airplane flotation devices.

The idea for Velcro came unexpectedly. In 1948, George de Mestral, a Swiss engineer, went hiking in the woods with his dog. Both he and the dog came home covered with burrs that had stuck to them during their walk. Suddenly, an idea occurred to him: Could what made the burrs stick on clothes have commercial use as a fastener? Studying a burr under a microscope, he discovered that it was covered with tiny hooks, which had allowed many of the burrs to grab onto clothes and fur that brushed up against the plants as he and his dog passed by.

Armed with this idea, de Mestral spent the next eight years developing a product he called Velcro, a combination of the words velvet and crochet. He obtained a patent on his hook-and-loop technology in 1955 and named his company Velcro. Few people took de Mestrals invention seriously at first, but it caught on, particularly after NASA used Velcro for a number of space flights and experiments. In the 1960s, Apollo astronauts used Velcro to secure all types of devices in their space capsule for easy retrieval. Starting in 1968, shoe companies like Puma, Adidas, and Reebok integrated Velcro straps into childrens shoes.

A 1984 interview between television talk-show host David Letterman and Velcros U.S. director of industrial sales ended with Letterman, wearing a suit made of Velcro, launching himself off a trampoline and onto a wall covered in Velcro, sticking to it. This widely publicized stunt furthered the craze, resulting in more companies adapting Velcro into their products.

Gunpowder

Legend has it that Chinese scientists searching for the elixir of life experimented with potassium nitrate, sulfur, and charcoal, causing an explosion that had very little to do with immortality. The emperor was entertained on his birthday with a reenactment of the experiment, marking possibly the worlds first fireworks display. Colorful explosions using gunpowder, of course, still mark special occasions today. But the explosive substance also has a dark past, and the use of gunpowder in war has changed the course of history more than any other weapon.

T he first wartime record of gunpowder is found in a Chinese military manual produced in 1044 C.E. On the battlefield, the Sung Dynasty used gunpowder against the Mongols to make flaming arrows. Those early battles used the new substance as a fire-producing compound that propelled flames across enemy lines. Later, crude bamboo rifles emerged.

Fearful that the technology would fall into the hands of enemies, the government forbade the sale of gunpowder to foreigners, and it remained in Chinese possession until the 13th century. It probably arrived in Europe by the Silk Road, and the English and French quickly developed the new tool to use in simple cannons during the Hundred Years War (13371453). The Ottoman Turks also successfully broke down the walls of Constantinople using gunpowder.

When the handgun appeared in 1450, operating as a miniature cannon, each soldier was issued his own weapon. The infantry was born, and with it the modern army. All thanks to this simple, ancient powder.

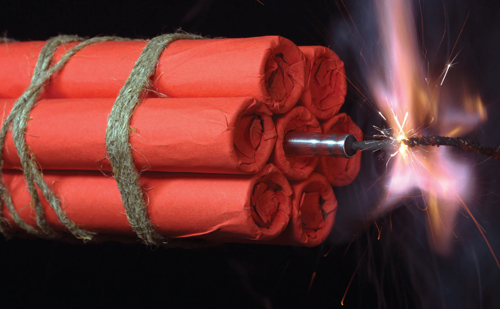

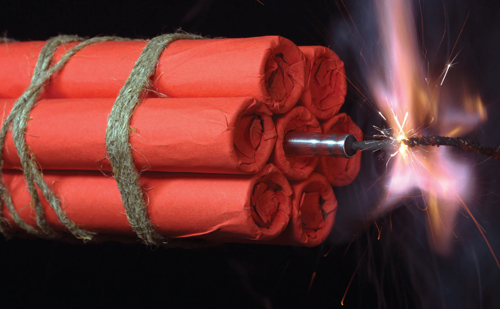

Dynamite

For Swedish chemist and prolific inventor Alfred Nobel, explosives were the family business. But they would also prove the source of one of his greatest inventions and the foundation of a global legacy.

W hile studying chemistry and engineering in Paris, Nobel met Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero, the inventor of nitroglycerin, the highly unstable liquid explosive containing glycerin, nitric acid, and sulfuric acid. The substance was considered too dangerous to have any practical application, but Nobel and his family recognized its tremendous potential and began using it in their factories.

After his studies and travel to the United States, Nobel returned home to work in his familys explosive factories in Sweden. In 1864, Alfreds younger brother Emil, along with several others, was killed in an explosion at one of the plants. Nobel was devastated by the loss and determined to create a safer version of nitroglycerin.