Great Inventors and Their Inventions

by

Frank P. Bachman

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by American Book Company in 1918. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-066-6).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Preface

This book contains twelve stories of great inventions, with a concluding chapter on famous inventors of to-day. Each of the inventions described has added to the comforts and joys of the world. Each of these inventions has brought about new industries in which many men and women have found employment. These stories, therefore, offer an easy approach to an understanding of the origin of certain parts of our civilization, and of the rise of important industries.

The story of each invention is interwoven with that of the life of its inventor. The lives of inventors furnish materials of the highest educative value. These materials are not only interesting, but they convey their own vivid lessons on how big things are brought about, and on the traits of mind and heart which make for success.

It is hoped that this book will set its readers to thinking how the conveniences of life have been obtained, and how progress has been made in the industrial world. While appealing to their interest in inventions and in men who accomplish great things, may it also bring them into contact with ideas which will grip their hearts, fire the imagination, and mold their ideals into worthier forms.

Contents

Part I

Inventions of Steam and Electric Power

CHAPTER I

James Watt and the Invention of the Steam Engine

U NTIL a little more than one hundred years ago, the chief power used in the production of food, clothing, and shelter was hand power. Cattle and horses were used to cultivate the fields. Windmills and water wheels were employed to grind corn and wheat. But most tools and machines were worked by hand.

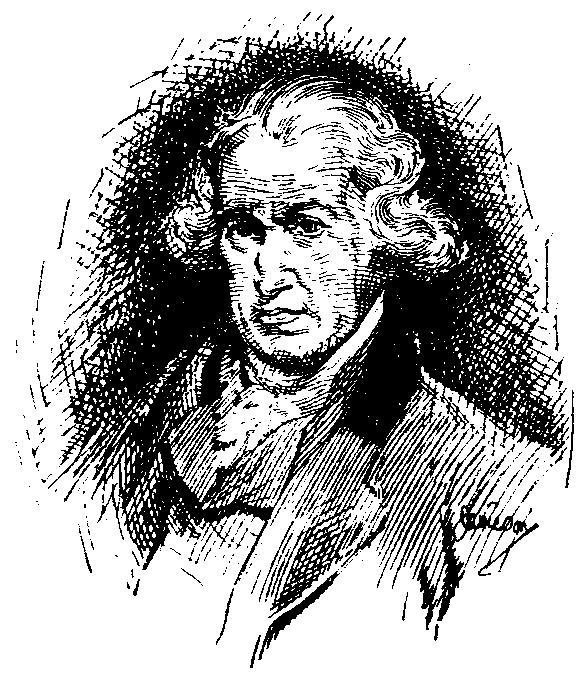

JAMES WATT

Men had, for many years, dreamed of a new power which would be more useful than either work animals, sails, windmills, or water wheels. This new power was steam. Yet no one had been able to apply the power of steam so that it would grind corn and wheat, spin and weave cotton and wool, or do any useful thing at all. The man who succeeded in giving to the world this new power was James Watt. Steam now propels ships over the Atlantic in less than a week. It speeds express trains across our continent in ninety hours, and it does a thousand other wonderful and useful things.

Childhood and Early Education

James Watt was born in 1736, at Greenock, Scotland, not far from Glasgow. His early education was received at home, his mother giving him lessons in reading, and teaching him to draw with pencil and chalk. His father drilled him in arithmetic and encouraged him in the use of tools. When at length James went to school, he did not at first get along well. This was due to illness which often kept him at home for weeks at a time. Still, he always did well in arithmetic and geometry, and after the age of fourteen he made rapid progress in all his studies.

Even as a small boy, James was fond of tinkering with things. This fondness was not always appreciated, as is shown by a remark of an aunt: "James Watt, I never saw such an idle boy; take a book or employ yourself usefully; for the last hour you have not spoken a word, but taken off the lid of that kettle and put it on again, holding now a cup and now a silver spoon over the steam, watching how it rises from the spout, and catching the drops of water it turns into. Are you not ashamed to spend your time in this way?"

Much of his time, as he grew older and stronger, was spent in his father's shop, where supplies for ships were kept, and where ship repairing was done. He had a small forge and also a workbench of his own. Here he fashioned cranes, pulleys, and pumps, and learned to work with different metals and woods. So skillful was he that the men remarked, "James has a fortune at his fingers' ends."

WATT AND THE TEAKETTLE

The time at last came for choosing a trade. The father had wished James to follow him in his own business. But Mr. Watt had recently lost considerable money, and it now seemed best for the youth to choose a trade in which he could use his mechanical talents. So James set out for Glasgow to become an instrument maker.

Learning Instrument Making

He entered the service of a mechanic who dignified himself with the name of "optician." This mechanic, though the best in Glasgow, was a sort of Jack-of-all-trades, and earned a simple living by mending spectacles, repairing fiddles, and making fishing tackle. Watt was useful enough to his master, but there was little that a skillful boy could learn from such a workman. So he decided to seek a teacher in London.

There were plenty of instrument makers in London, but they were bound together in a guild. A boy wishing to learn the trade must serve from five to seven years. Watt had no desire to bind himself for so long a period. He wished to learn what he needed to know in the shortest possible time; he wanted a "short cut." Master workman after master workman for this reason turned him away. Only after many weeks did he find a master who was willing to take him. For a year's instruction, he paid one hundred dollars and gave the proceeds of his labor. The hours in the London shops were long. "We work," wrote Watt, "to nine o'clock every night, except Saturdays." To relieve his father of the burden of supporting him, he got up early and did extra work. Towards the end of the year he wrote, with no little pride: "I shall be able to get my bread anywhere, as I am now able to work as well as most journeymen, though I am not so quick as many."

Jack-of-all-trades

In order to open a shop of his own, Watt returned to Glasgow. He was opposed in this by the hammermen's guild. The hammermen said that he had not served an apprenticeship and had no right to set up in business. They would have succeeded in keeping him from making a start, had not a friend, a teacher in the University of Glasgow, come to his aid, providing him with a shop in a small room of one of the college buildings.

Watt soon became a Jack-of-all-trades. He cleaned and repaired instruments for the university. Falling into the ways of his first master, he made and sold spectacles and fishing tackle. Though he had no ear for music and scarcely knew one note from another, he turned his hand to making organs. So successful was he, that many "dumb flutes and gouty harps, dislocated violins, and fractured guitars" came to him to be cured of their ills.