Copyright 2012 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com . Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission .

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wei, James, 1930

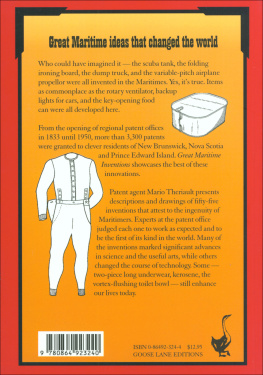

Great inventions that changed the world / James Wei, Princeton University.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-470-76817-4 (hardback)

1. Inventions. 2. Technological innovations. I. Title.

T15.W45 2012

600dc23

2011053470

Foreword

The Earth is now 4.5 billion years old. Yet, virtually all the knowledge and inventions available today appeared in the last century or so. Extrapolate that pace of change forward and accelerate it and one has an idea what life will be like a century, or millennium, in the future. Or perhaps more accurately one has no idea.

That is not to suggest that all previous times were Dark Ages of Innovation: On the contrary, there was the lever, wheel, wedge, stirrup, long bow, telescope, and more, but nothing like the veritable flood of innovation that engulfs this fast-forward world in which we live today.

Various studies have shown that 5085% of the growth in US GDP over the past half century and two-thirds of the productivity increase (read standard of living gain) are due to advancements in science and engineering. The US National Academies and many other organizations have concluded that the future quality of life in developed nations that have huge competitive disadvantages in the cost of labor will depend upon their ability to innovate; that is, to create knowledge through extraordinary scientific research, to translate that knowledge into products and services through engineering leadership, and through world-class entrepreneurship shepherd those products and services across the Valley of Death, where so many new innovations fail for economic reasons, and into the marketplace.

This is not easy. Only about 1 patent application in 100 leads to a successful product. Thomas Edison, seeking a filament for an electric light bulb, once explained, I have not failed. I have found 10,000 ways that won't work. And 60% of new companies go out of business in less than 3 years.

Today, the populace of Earth must produce $1.5 million of goods and services each second , 24/7, merely to preserve the existing standard of living on the planeta standard under which half the population still survives on less than $2 per day. The Red Queen, speaking to Alice in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass , offers sound advice: Here , you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!

Consider a snapshot of the lifetime of the author of this Foreword. He began his engineering training performing calculations using three sticks of wood and two pieces of glass; his youth included occasional summers of confinement to his yard due to the fear of polio; his early professional years included helping put a dozen friends on the moon; and his business years ended with him working with 82,000 engineering colleagues, along with experts in many other fields, to create $1000 of new business every second, merely to keep the firm that employed them all afloat. Craig Barrett, the retired CEO of Intel, points out that 90% of the revenues that company receives on the last day of the firm's fiscal year are derived from products that did not even exist on January 1 of that same year. It took 55 years for one-fourth of the US population to have an automobile, 35 years for the telephone, 21 years for the radio, 13 years for the cell phone, and only 7 years for the World Wide Web.

In this book, Professor Jim Wei, a superbly qualified guide, conducts uspoets and physicists alikethrough a fascinating and informative tour of what it means to invent. This is a tour punctuated with risk-taking, failure, determination, insightfulness, luck, and, yes, even resounding success. We watch as scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs collect a great deal of scar tissueall without pain for us. It seems that success in innovation is not always where one looks for it: penicillin was discovered when Sir Alexander Fleming noticed that the bacteria he had been studying were not growing near the mold that had accumulated on a Petri dish that had been contaminated. A researcher of the Raytheon Corporation conceived the microwave oven when he noticed that a candy bar he was carrying in his pocket at the company's radar lab was melting. But, importantly, Louis Pasteur reminds us that Chance favors only the prepared mind.

Margaret Thatcher notes that... although basic science can have colossal economic rewards, they are totally unpredictable. Nevertheless, the value of Faraday's work today must be higher than the capitalization of all shares on the stock exchange.... Indeed, it is doubtful that the early researchers in quantum mechanics had iPods or GPS in mind as they labored in their laboratories.

Today, the character of innovation itself is changing. While there will always be room for the Edisons, Fultons, and Whitneys, innovationin both the science and the engineeringis increasingly becoming the province of teamsoften of very large teams possessing very diverse backgrounds. This is the era of Big Science. Astronaut Buzz Aldrin observes that It's amazing what one person can do, along with 10,000 friends. Inventions are now being found with increasing regularity at the intersection of disciplines. Plastics are made through the efforts of tiny bugs; and if one is dissatisfied with the output of these bugs, one need to only reengineer the bugs.