Disclaimer: Although this book is based on considerable research, the author(s) and the publisher(s) make no claims regarding the completeness or accuracy of the information included here. All topics are in no particular order of any importance.

Note: For the sake of this book, all topics will be classified under the argument of being a Lost Invention only. For example, the Antikythera Mechanism and the Baghdad Battery have been debated to also be Out of Place Artifacts (OOPARTS). For more information on that topic, please check out my book, 10 Out Of Place Artifacts That Suggest a Higher Intelligence or Conspiracy to see the other side of this debate on those two topics, and a whole lot more!

Introduction: The Lives of Tools

Historys great inventions seem to have lives of their ownindeed, even minds of their own. For one thing, they have a way of popping into the world whenever and wherever they like. Consider two of the most important inventions of all timewriting and agriculture. Writing is believed to have showed up in at least three different places: Mesopotamia, China, and Mesoamerica. Farming arose several times, in both the Old World and the New World.

Inventions might also be said to have a sense of mischief. Mechanical gears, for instance, were long thought to have been invented by the Chinese engineer Ma Jung in the third century AD. He used them for his amazing South-Pointing Chariot, a horse-drawn vehicle toting a statue that pointed south regardless of which way it actually moved.

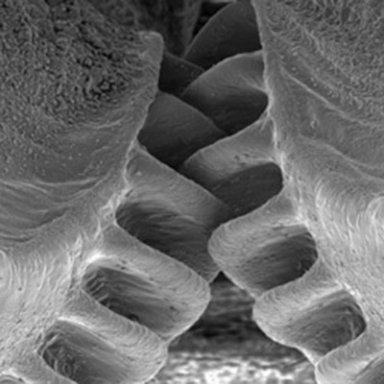

But the illusion of human ingenuity got a rude shock in 2013, when scientists found out that gears had been in use much earlier than thatindeed, for longer than humans had even existed.

Photo of the Isus Nymph via Creative Commons

As a University of Cambridge news story put it,

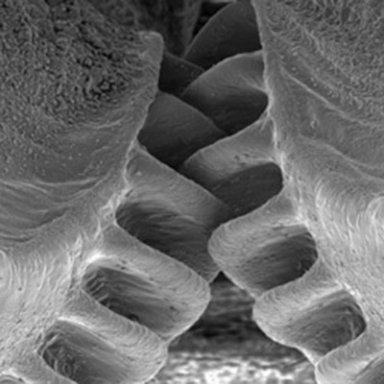

The juvenile Issusa plant-hopping insect found in gardens across Europehas hind-leg joints with curved cog-like strips of opposing teeth that intermesh, rotating like mechanical gears to synchronize the animals legs when it launches into a jump.

Cog wheels connecting the hind legs of the plant hopper, Issus.

Credit: Burrows/Sutton via Creative Commons

So it turned out that gears had not actually been invented by humans at all; the juvenile Issus developed them millions of years ago through good old-fashioned Natural Selection. Such a realization brings into question the origins of other tools. For example, credit for inventing movable type traditionally goes either to the Asian alchemist Bi Sheng or the European goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg. But maybe its smarter to give the glory to movable type itself, which seemed to have willed itself into existence in both first-century China and fifteenth-century Germany. (At least no evidence his turned up of ancient insects tinkering with a printing press!)

In this little book, we are not so much interested in how tools popped into the world, but how they sometimes popped out of it and why. Lost inventions might be said to be those which got themselves invented, then decided to disappear and go into hiding for a time.

Some of them seem to have departed with good reason

An electric battery in ancient Mesopotamia must have found life to be pointless, lonely, and boring, with no electrically-powered tools yet in existence. And so it bowed out until 1800, when its potential was better appreciated by the likes of Alessandro Volta.

After the steam engine arranged for its own invention in Ancient Greece, it found itself treated as a humble toy, whirling round and round to no purpose at all. Why not go underground until it could find glory in an age of machine-driven ships and locomotives?

When the digital computer got itself conceived in the early nineteenth century, perhaps it soon realized that steam power was not a very good fit for it. So it went away until the mid-twentieth century, when electronic circuitry was coming of age.

Other inventions fell victim to the flaws, failings, and caprices of their human proxies:

When the destructive power of napalm first presented itself in it AD 673, its Byzantine wielders kept its recipe such a closely guarded secret that pretty soon nobody had any idea how to make it. It then had to hibernate until the markedly more savage twentieth century, when no particular nation had a monopoly on mass murder.

The analog computer made its entrance in Ancient Greece, only to be carelessly drowned in a shipwreck. It stayed submerged for centuries thereafter, until at last it flourished in the hands of twentieth-century nerds in the form of the slide rule.

And who can say why the earthquake detector didnt find an enduring place in the tectonically unstable world Ancient China? It seems instead to have fallen victim to the shortness of the human attention span until more dependable users showed up in the 1800s.

This book tells the stories of these and other devices, and how they made their ways into the world only to slip away into the sad limbo of lost inventionssome of them for a short time, some of them for many centuries.

Links to Sources

Ancientscripts.com, Origins of Writing Systems. http://www.ancientscripts.com/ws_origins.html

New World Encyclopedia, History of Agriculture. http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/History_of_agriculture

Lock Haven University, The Chinese South-Pointing Chariot. http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/make-chinese/southpointingcarriage.htm

The University of Cambridge, Functioning Mechanical Gears Found in Nature for the First Time. http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/functioning-mechanical-gears-seen-in-nature-for-the-first-time

1. The Computer that Came Out of the Sea

Just a few decades ago, every self-respecting nerd was armed with a slide rule. It looked like a ruler with a sliding strip in the middle, and it came up with quick solutions to math problems, especially multiplication and division. Unlike todays more common pocket calculators, the slide rule was analog rather than digital. To understand the difference, think of an analog clock, with its hands moving continuously around a dial, in contrast to a digital clock, with its abruptly changing numbers. Analog calculates spatially; digital calculates with separate numerals. The slide rule was an extremely simple example of an analog computer as opposed to a digital computer.

The worlds oldest analog computer is also the most mysterious. It was discovered by sponge divers in 1900 in an ancient shipwreck off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera. It is now known as the Antikythera Mechanism, and it is believed to have been built somewhere around 100 BC. Housed in a shoebox-sized wooden frame, the mechanism was an extremely complex system of about 37 bronze gears. On the outside of the box were symbols representing the Sun, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, and all the other then-known heavenly bodies, including the signs of the zodiac.

Nobody had any idea what the Antikythera Mechanism actually did until decades after its rediscovery. By 1959, X-ray analyses had proven that it was nothing less than a moving model of the heavensan early but far from primitive analog computer. It could show the positions of the planets and the phases of the moon for any chosen date starting in 205 BC, and it could accurately predict solar and lunar eclipses. It was also used to schedule the dates for athletic events, including the Ancient Greek Olympics. For its time, it was by far the most intricate machine of its kind known to have been built.