About the Author

Julie Halls works in the Advice and Records Knowledge Department at The National Archives, London, and is a specialist in registered designs.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Things Come Apart:

A Teardown Manual for Modern Living

Objectivity:

A Designers Book of Curious Tools

Cyclepedia:

A Tour of Iconic Bicycle Designs

The Bicycle Artisans

Design Since 1945

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

FOR MY SON, OLIVER

THANK YOU TO MY FATHER, LAURIE; MY BROTHER, ROBIN; ANN & MY FRIENDS BARBARA & LINDSEY FOR THEIR SUPPORT AND ENCOURAGEMENT

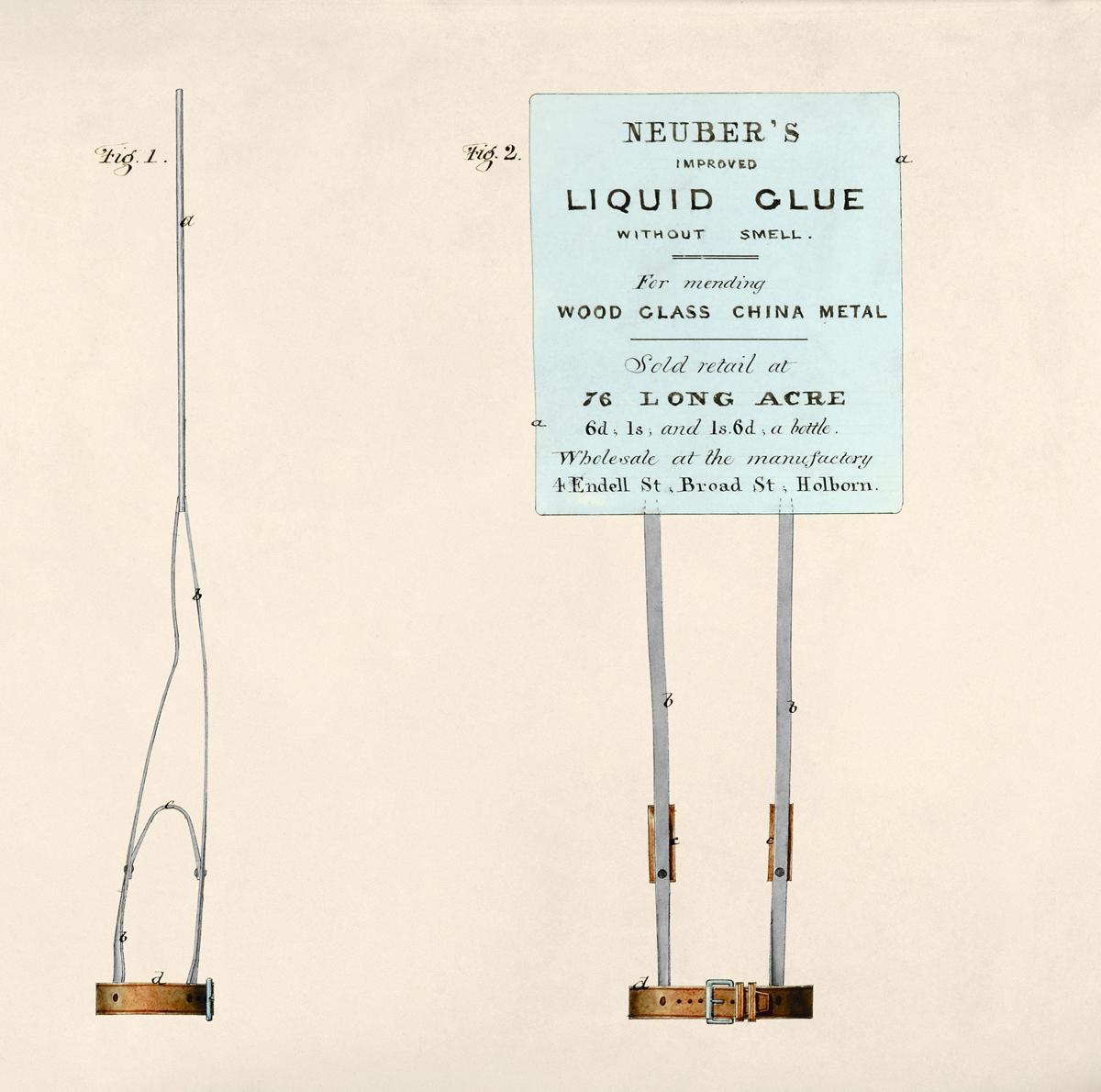

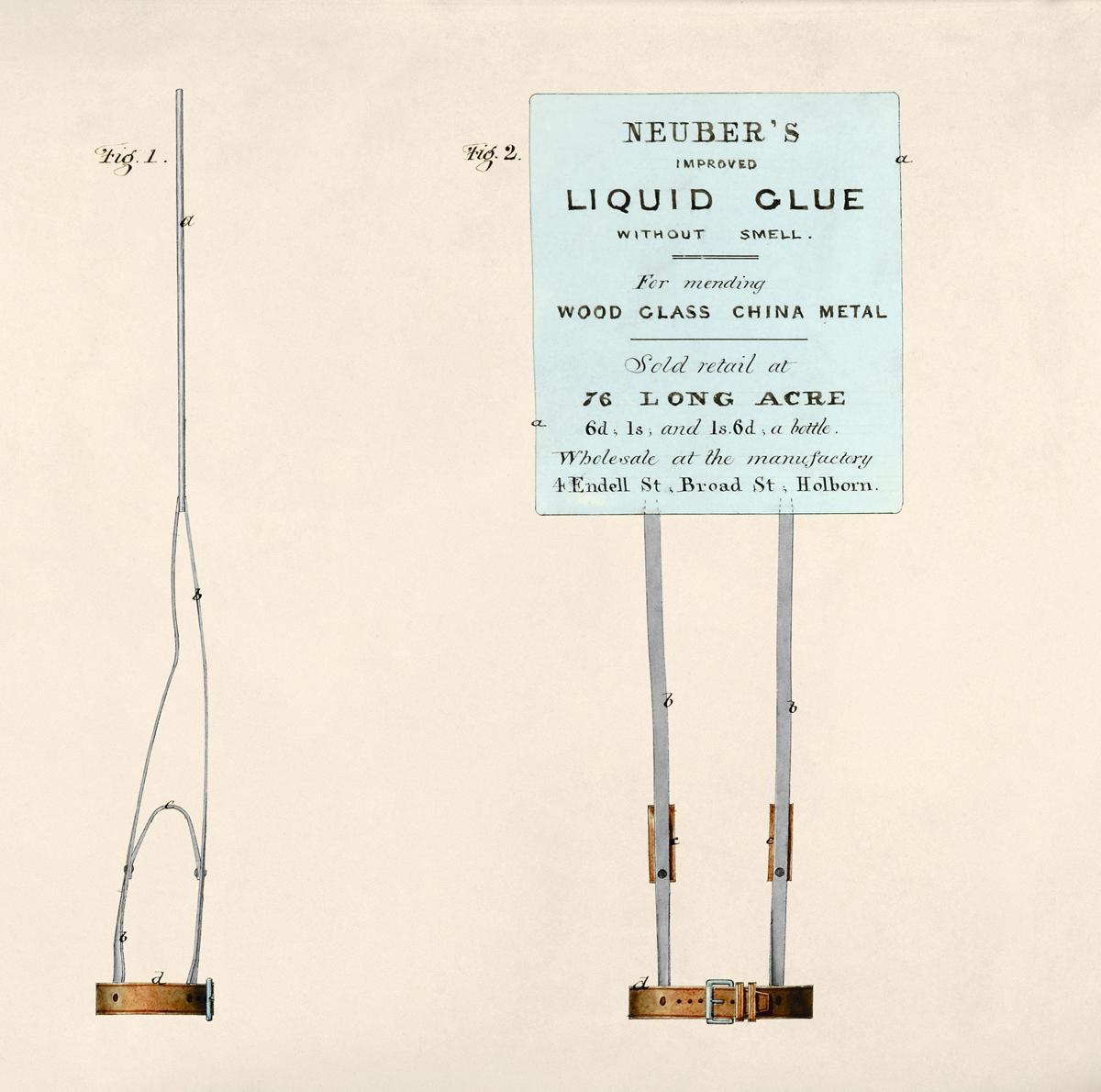

Design for a placard holder, 1848

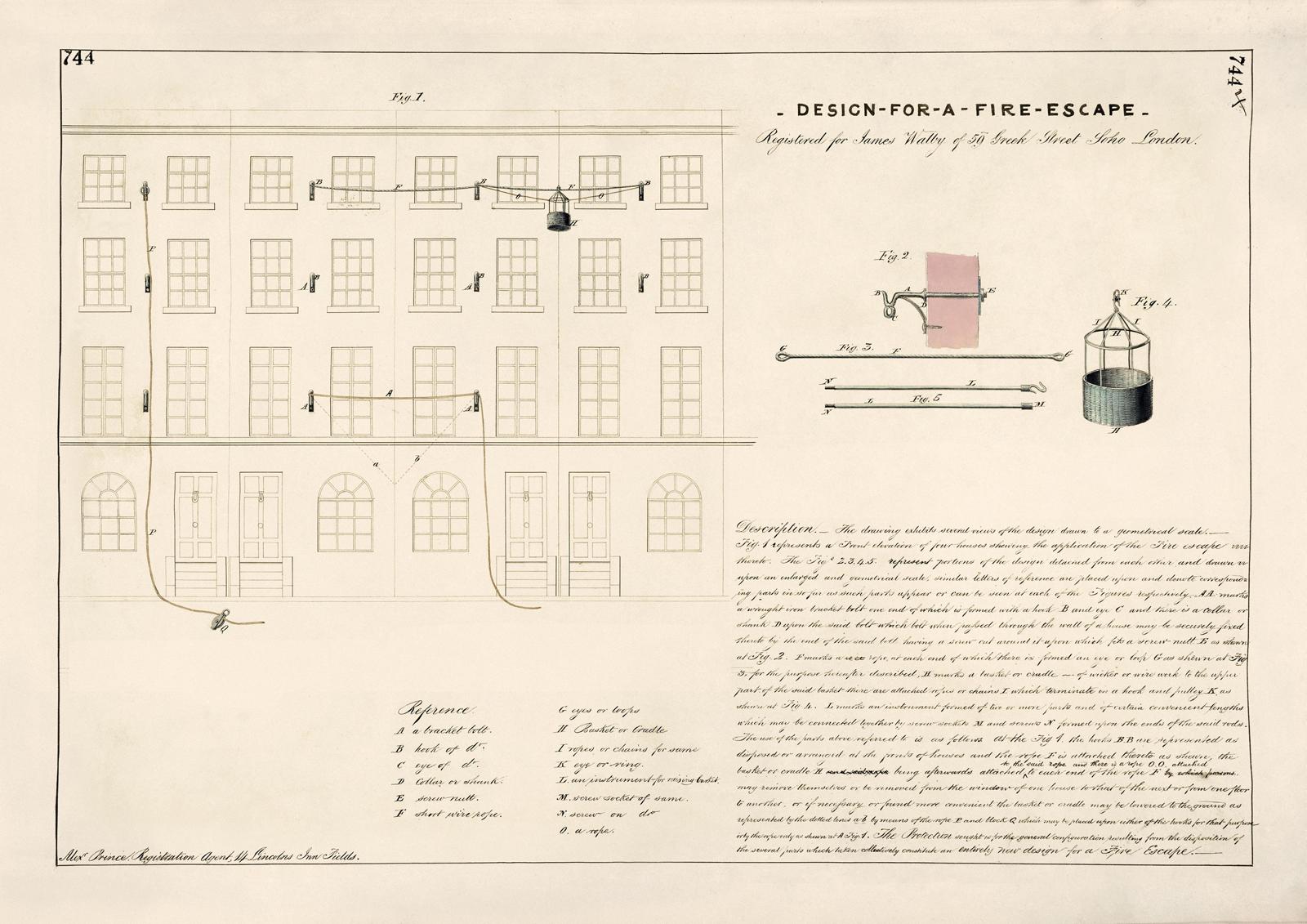

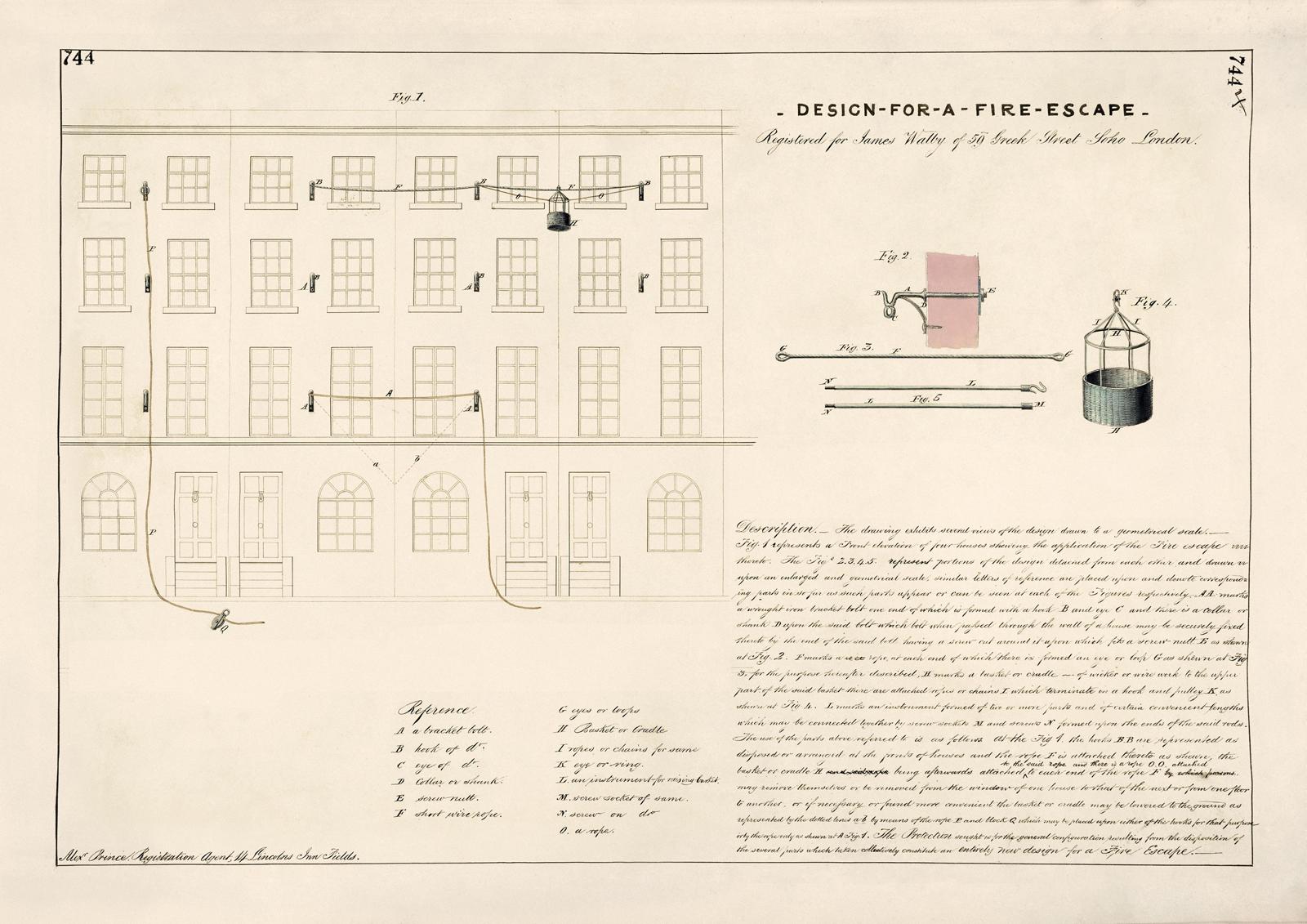

Design for a Fire Escape, 1846

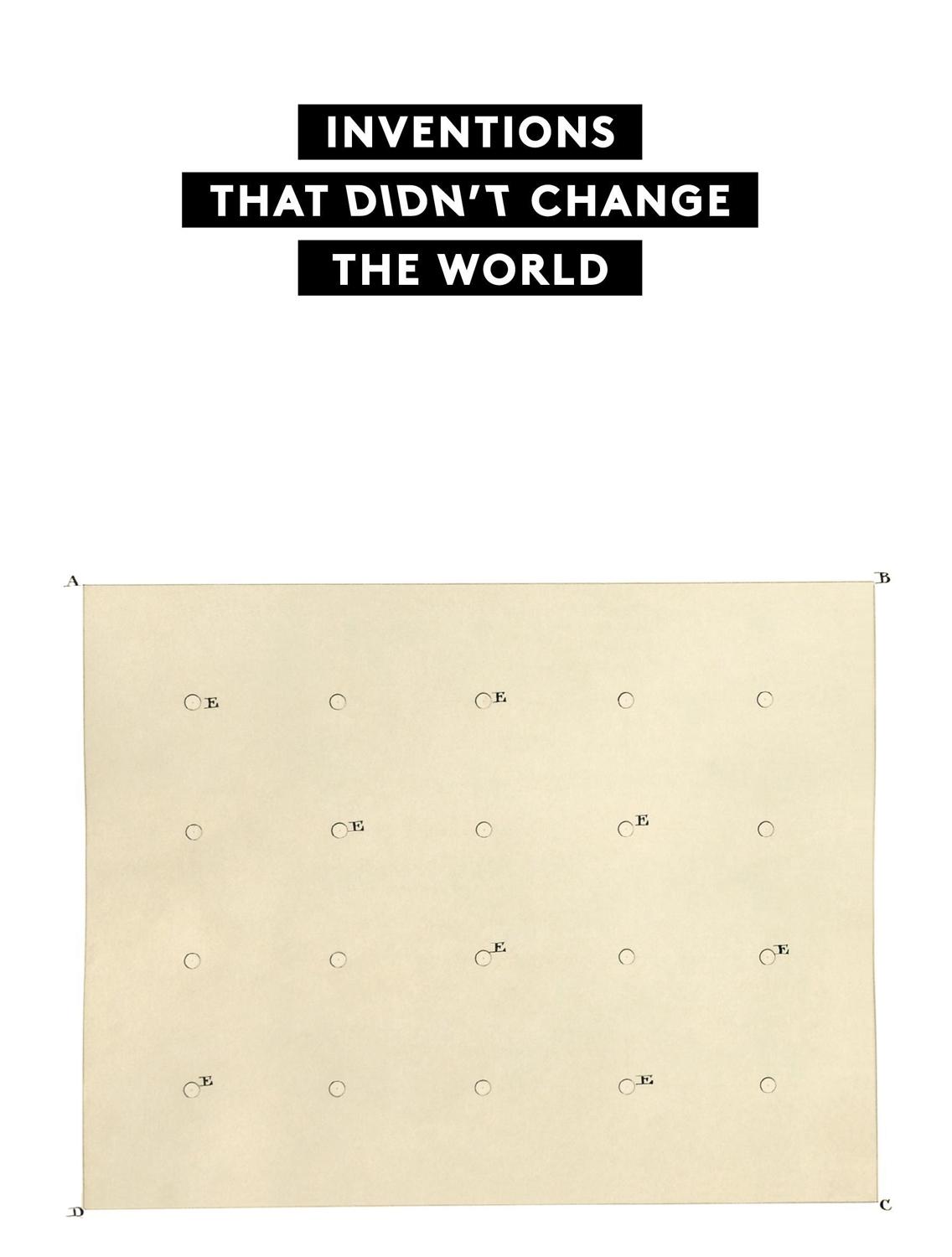

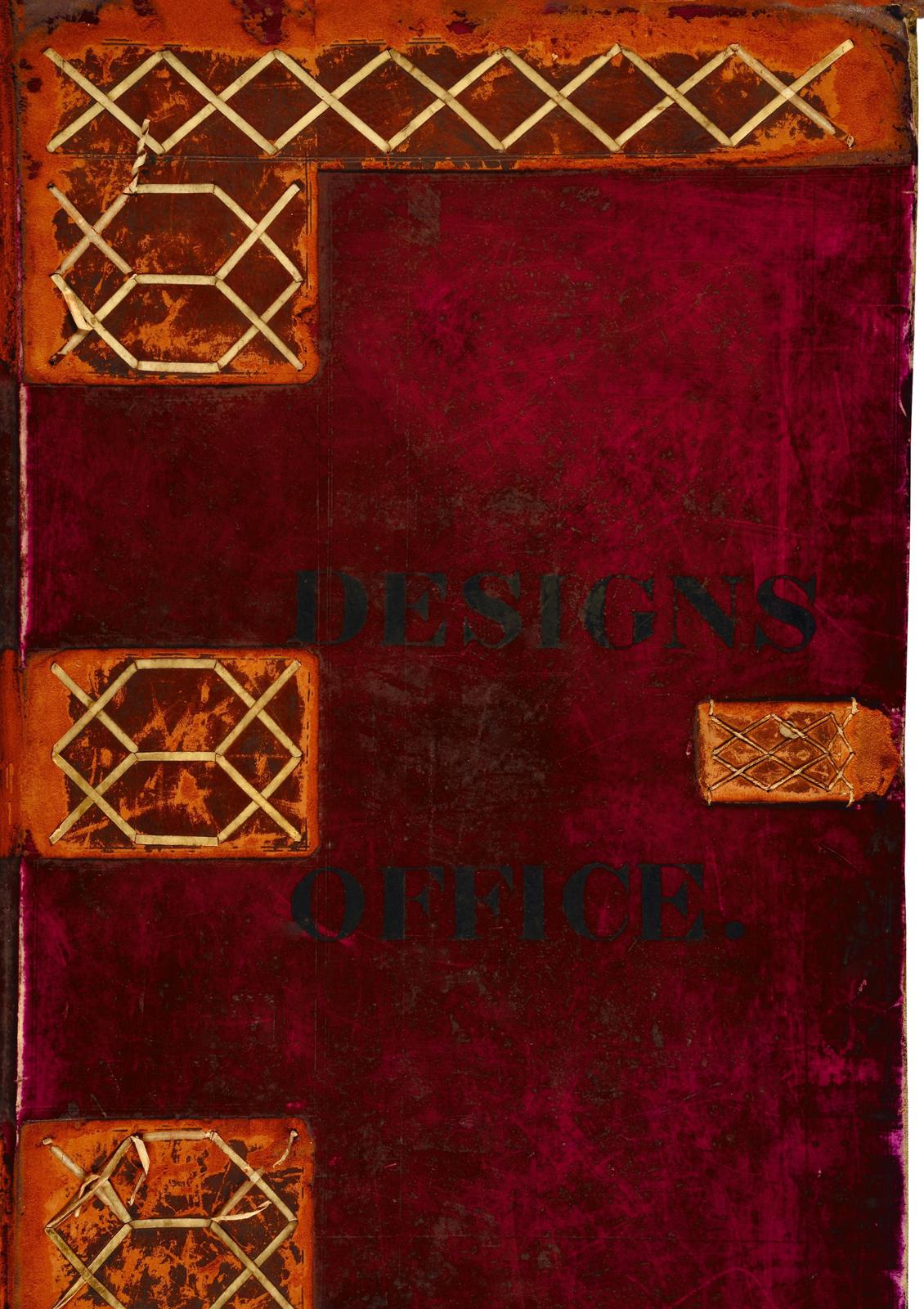

Cover binding of a volume of designs BT 45/28, 187478

CONTENTS

The inventions in this book tell a story of nineteenth-century enterprise, enthusiasm and, above all, optimism. Each gadget, machine or apparatus, however bizarre it might seem now, was copyrighted by an inventor filled with hope that it would prove popular, useful and if others shared his vision profitable. The Victorian era was one of amazing inventiveness, and many inventions of the period were so successful that they changed the way we live such as the telephone, steam engine, railway and light bulb. However, there were also thousands of inventions that we have long since forgotten or that never saw the light of day.

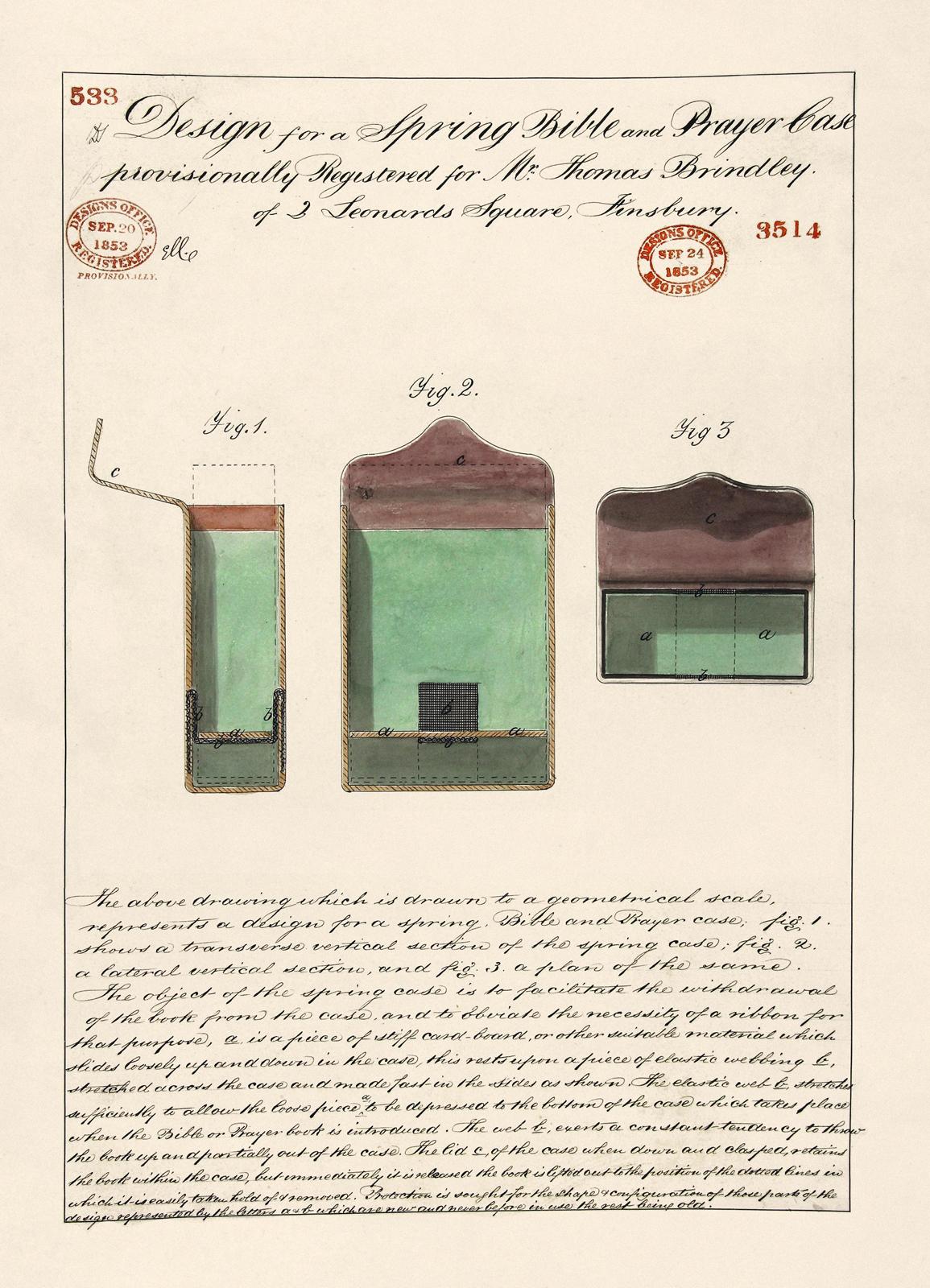

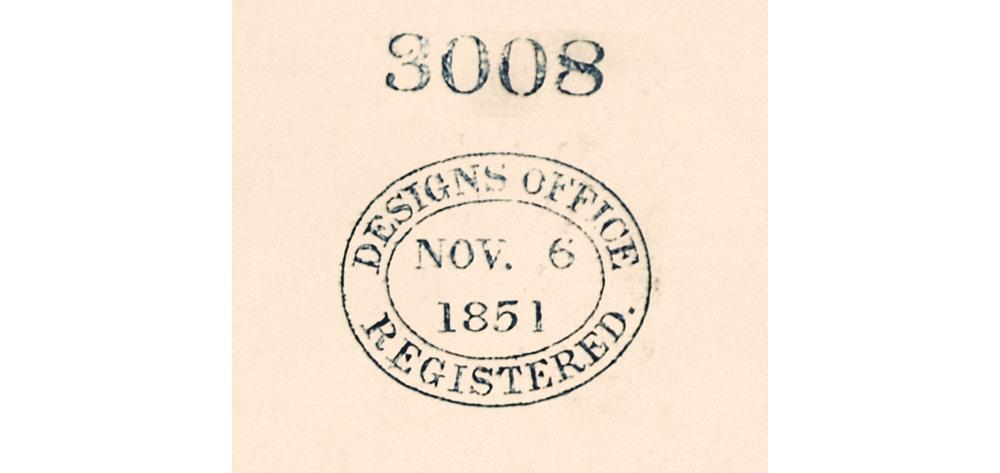

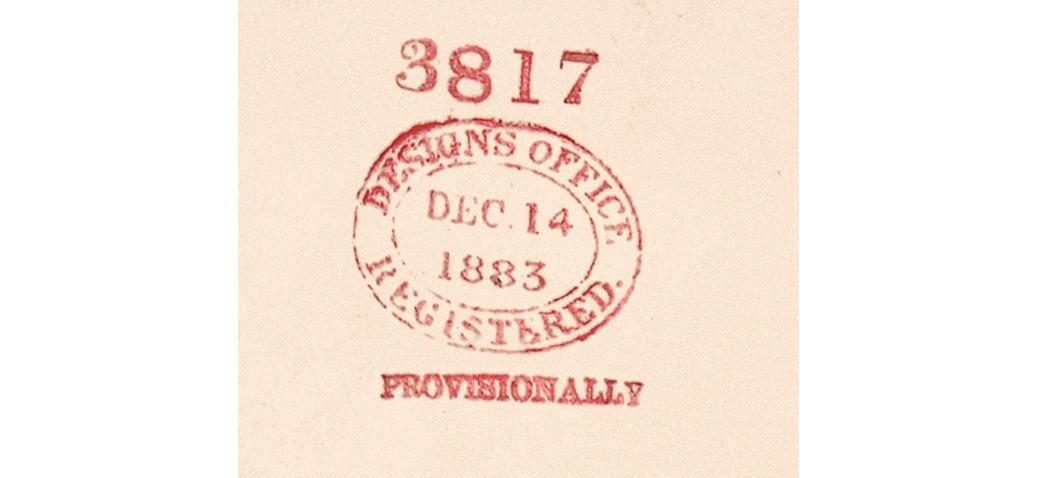

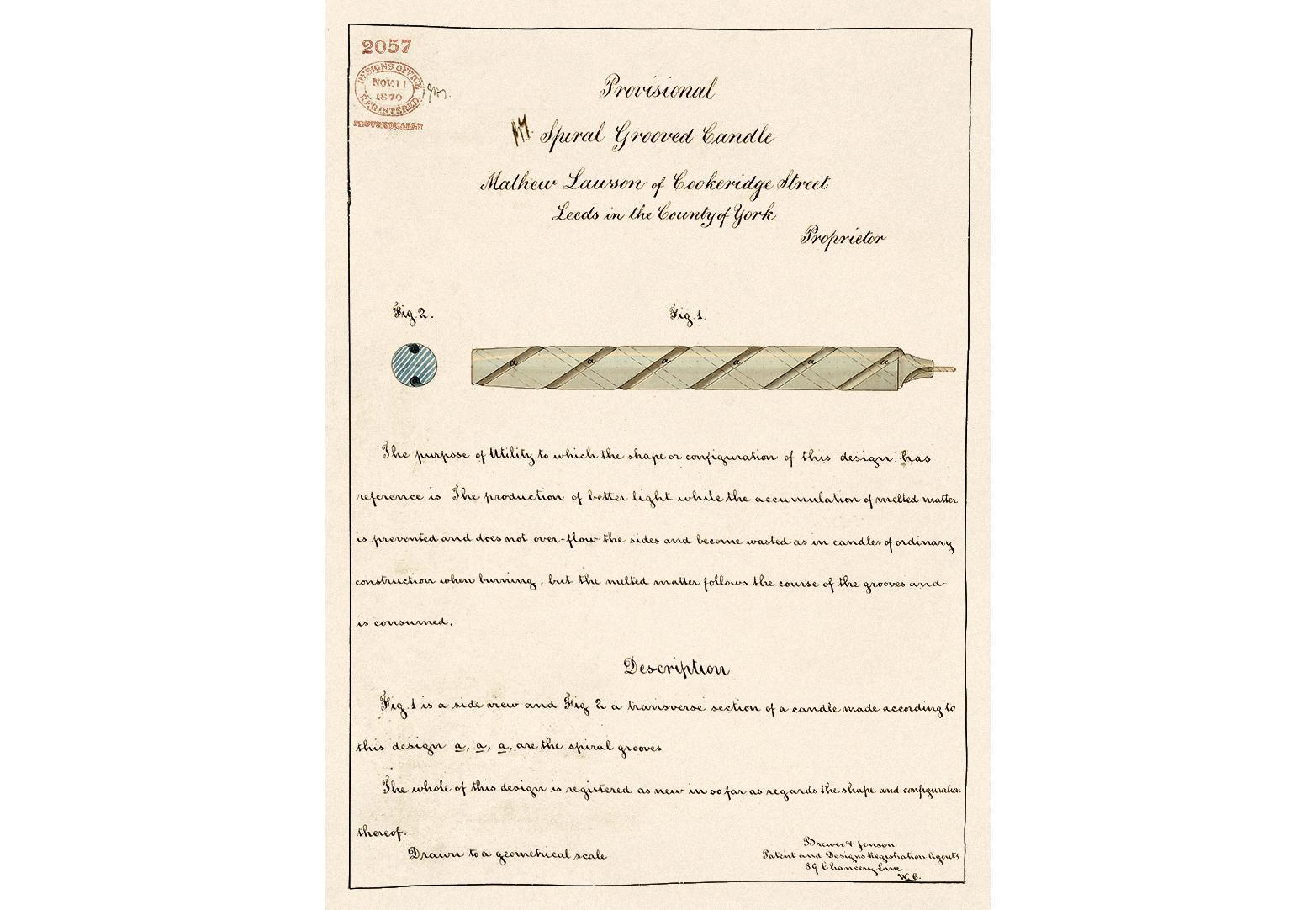

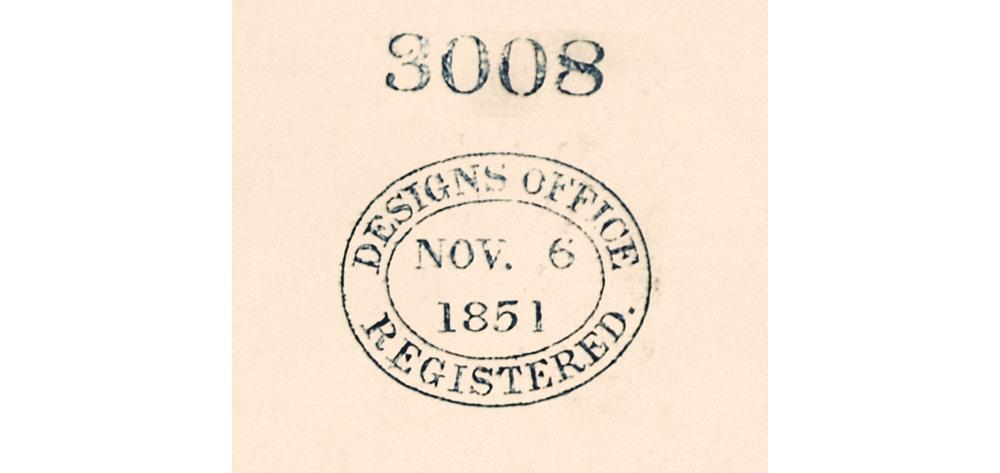

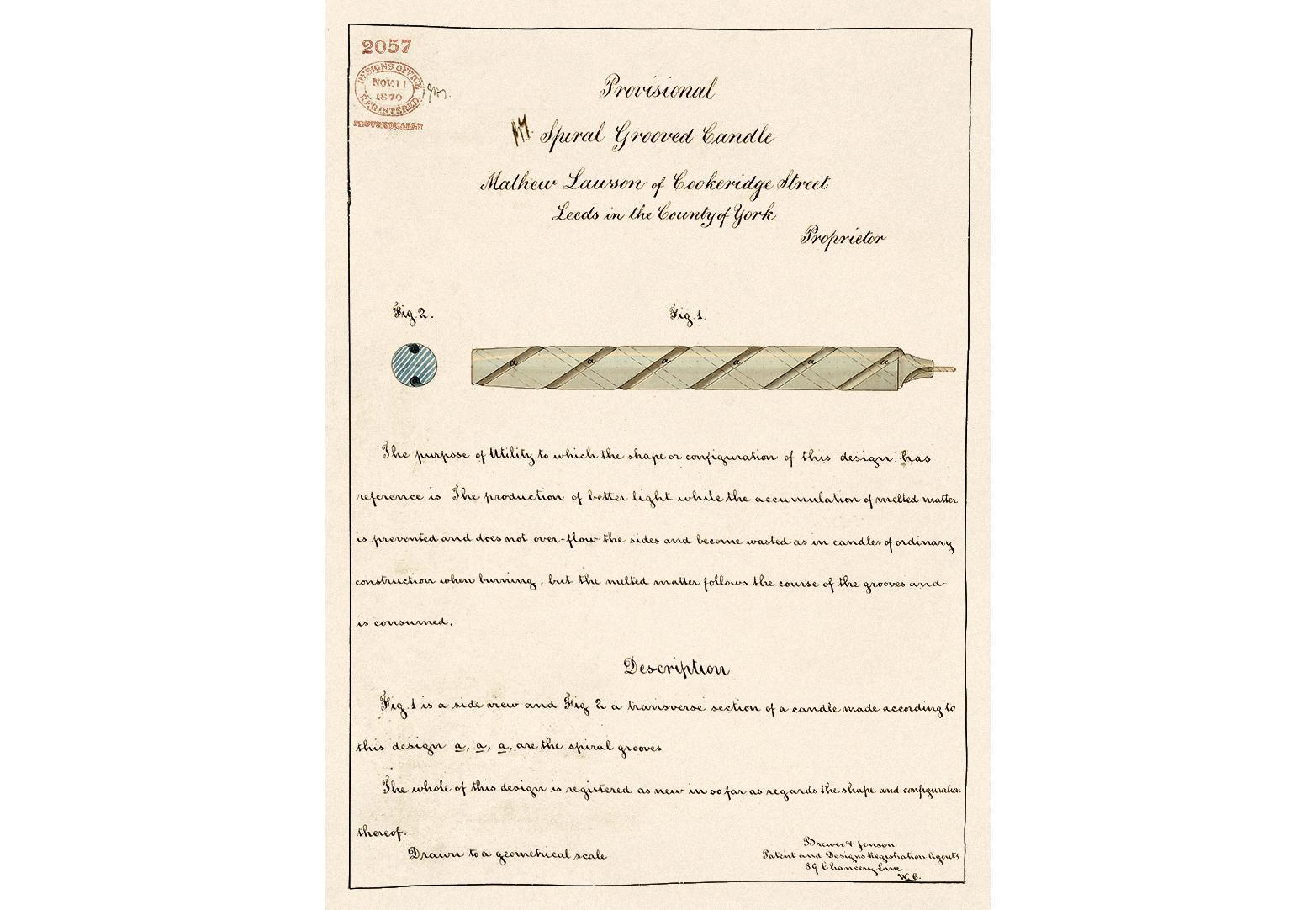

Everyone who applied to copyright an invention had to provide two identical drawings of the design to the governments Designs Registry at Somerset House, London. If successful, one copy of the drawing would be stamped and returned to the copyright holder. The other would be pasted into a huge, leather-bound volume of designs and retained by the Registry, part of the Board of Trade. These volumes are now in the care of The National Archives, which look after more than 1,000 years of UK government records. Most of the inventions, dating back to 1843, have never been seen by any but a few determined researchers. This is partly because of the complex system of numbering adopted by the Registry, which can make it difficult to track down specific designs, and perhaps also because the volumes are large, dusty and extremely heavy. Although the documents are now carefully stored in temperature-controlled conditions, this was not always the case during their long history, as can be seen by the damage to some of the drawings. Although some inventions have now been catalogued and the details of the proprietor (the copyright holder), date of registration and a brief description of the design can be found on The National Archivess online catalogue, few of the images have been digitized.

Spine of a single volume of designs, BT 45/14, 185051

The activities of the inventors, many of them amateurs, were part of a wider culture that celebrated as a national triumph the technological achievements and industrial advances made in Britain. By the middle of the nineteenth century it was both the greatest manufacturing nation and the greatest trading nation in the world. The process of industrialization that began in the eighteenth century paved the way for a period of immense industrial productivity based on steam technology. Huge advances were made in the mining of coal, minerals and other raw materials, and in the production of iron, textiles and manufactured goods. These advances allowed Britain to mass-produce goods more efficiently and sell them more cheaply than any other nation.

This powerful position was further strengthened by improvements in transport and communication technologies. The railways moved freight and passengers around the country at great speed, providing new opportunities for commerce and leisure activities. The Illustrated London News described the railways as the grandest exponent of the enterprise, the wealth and the intelligence of our race, Men like Richard Arkwright, credited with creating the modern factory system, George Stephenson and Richard Trevithick, pioneers of steam transport, and the visionary engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, were all national heroes.

As the prosperity of the nation increased, a greater proportion of the population than ever before had disposable income to spend on the huge range of goods being produced. The affluent and expanding middle classes, in particular, helped ensure a strong domestic demand for goods, fuelled by an increase in advertising along with lifestyle books and journals.

The press in general expanded hugely at this time, and the sense of excitement and widespread interest in technological innovations were reflected in the growth of popular magazines and journals aimed at ordinary mechanics and artisans as well as highly qualified engineers. There was an intense interest in how things worked, which crossed the barriers of class. Publications such as The Mechanics Magazine, Popular Science Monthly and The Engineer contained highly technical articles about the latest inventions and technological developments and lively letters demonstrating that readers had a sound understanding of the subject.

A registration stamp. Blue ink was used until mid-1852

An example of a provisional registration stamp

Provisional Spiral Grooved Candle*, 1870

The Victorians tended to imbue every aspect of life with a sense of morality, which included a powerful belief in individualism, self-respect and self-reliance there was a feeling that people should make their own way in the world. Each issue of the Mechanics Magazine, for example, had on its title page a morally improving quotation designed to inspire its readers.

This belief in self-reliance was encapsulated in Samuel Smiless best-selling book Self-help; with illustrations of character and conduct, published in 1859. There is a strong emphasis on industry meaning the human quality of industriousness, as well as machine production and inventors and engineers are described in heroic terms. There are numerous homilies describing the determination of successful inventors to succeed in the face of setbacks. Smiles emphasized that the fruits of labour could be enjoyed by people at any level in society who were prepared to work hard and persevere. Individual effort could enable inventors to rise from the lowest social ranks. In this environment where technology was a source of fascination and admiration inventors were seen as heroic and morally superior individuals, and ordinary men were encouraged to work hard in order to achieve success.