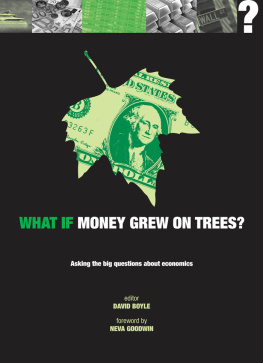

WHAT IF MONEY GREW ON TREES?

Asking the big questions about economics

editor

DAVID BOYLE

foreword by

NEVA GOODWIN

At a time when the banking system seems to be failing and the whole idea of capitalism appears to be up for debate, What If Money Grew on Trees? challenges a team of experts to put their minds to 50 speculations on economics. The questions they address turn accepted concepts on their heads, consider what would happen if existing constants were changed and ask why we do things the way we do.

*

Presents 50 sideways views on the world of economics, each one written by a leading scholar

*

Thought-provoking speculations engage the reader while conveying the essential basics

*

A new way of digesting knowledge that brightens up the dinner party debate

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Ivy Press

210 High Street

Lewes

East Sussex BN7 2NS

www.ivypress.co.uk

Copyright The Ivy Press Limited 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage-and-retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright holder.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Print ISBN: 978-1-78240-046-2

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78240-117-9

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-78240-118-6

This book was conceived, designed and produced by Ivy Press

Creative Director: Peter Bridgewater

Publisher: Jason Hook

Art Director: Michael Whitehead

Editorial Director: Caroline Earle

Design: JC Lanaway

Illustrator: Ivan Hissey

Historical text and introductions: David Boyle

Distributed worldwide (except North America) by Thames & Hudson Ltd., 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX, United Kingdom

Contents

FOREWORD

M ore than four decades ago I was a young mother with very young children. I had never taken an economics course in school or college, but I had a burning question that caused me to seek out the Boston location of the US Statistical Office and pick up a copy of the statistical abstract of the US Census, 1970. I was intensely conscious of the economic value of parenting, home health and nutrition activities, and other kinds of homemaking, and painfully aware of how little society tends to value that work or pay for it. I wondered how much we would have to tax paid work to pay for the absolutely vital caring work. (After many hours poring over my statistical abstract I came to the conclusion it was at least 25 per cent.)

What made me feel as well as think was looking at the statistics for agriculture seeing the number of farms in the USA decreasing year after year. I remember sitting with tears running down my face, because I knew how much heartache went with the loss of those farms. Irish playwright (and co-founder of the London School of Economics) George Bernard Shaw used to say that it took a civilized man to be deeply moved by statistics. That may be so, but it convinced me as a relatively civilized woman that it also took an economist. So, realizing that I was heading inevitably for a career change, I went back to college and became one.

To start with, the question I most wanted to answer was Why dont our wages reflect the real value of work to society? I have also been motivated by a range of related questions, such as How might the economic system reflect our human values better than it does at the moment?

Since then, I have been a working economist, and have written textbooks and struggled to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding about the things that really matter. The heart of economics needs to be asking difficult questions about the world. This is a book of difficult questions, too, asking What if? sometimes about the present and sometimes about what actually happened in history. The answers are not definitive they are written by a range of people who do not necessarily agree with one another. But they are designed to encourage people to think deeply about the way the world is, and the way the economic system is and whether it might be different.

The questions cover everything from money to work and beyond, and I hope that reading the book will get people into the habit of asking difficult questions themselves. Why do we believe in money? What choices or lack of choices lead us to the work that fills our lives? Why do bankers get paid so much more than nurses? Because the questions we ask are not just the beginning of wisdom, they are also the beginning of change. To quote George Bernard Shaw again: Some men see things as they are and ask why; others dream things that never were and ask why not. I might also add: they ask What if?

Neva Goodwin

Co-director of the Global Development and Environment Institute at

Tufts University, near Boston, Massachusetts, USA, and lead author

of Microeconomics in Context and Macroeconomics in Context.

INTRODUCTION

E conomics began with the ancient Greeks, and came into its own after the Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith published his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776. The next generation or two threw up a whole range of statisticians, political economists and mathematicians who founded the discipline we know today.

But it is a strange discipline, part art, part science with advocates on both sides. Some economists prefer graphs and formulae; some prefer as the great British economist John Maynard Keynes put it an idea that starts with a great woolly monster inside my head. These days, the emphasis is on the graphs, so much so that in 1999 there was an uprising against economics teaching at La Sorbonne in Paris by students who wanted to be taught in what they called a less autistic manner.

The Post-Autistic Economics movement begun by these students had an important objective, which was to make sure that all those formulae and models of the way that money works did not prevent economists from being able to see the real world. They wanted economists to understand the insights that other disciplines, like psychology or biology, can provide about the way people live, behave and spend their money.

The Sorbonne students achieved their objective. There was a government inquiry into economics teaching which vindicated them, and the curriculum was changed. There were also follow-up petitions along similar lines by economics graduates in other parts of the world. However, despite this success, there is still an issue about the way some mainstream economics departments cling to their formulae, allowing them to compromise with the way the real world actually works and forget that economic history was once full of other possibilities.

So let us dream for a moment that economics was not, as they say, the dismal science, and was really the barefoot, enthusiastic business that its greatest proponents would like it to be. Let us imagine that you could be an amateur economist, armed only with a notebook and a calculator, going out like Sherlock Holmes to understand a complex world. Because that is what we have tried to achieve in this book.

We have asked a number of economists and economics writers, who come from very different points of view, to do what economists are trained to do, which is to predict and to explain. What would happen if money grew on trees? What would happen if a whole number of shifts occurred in the way that the economy or the world happens to work at the moment? Dont let us guess the answers let us have expert speculations by people who have been wondering about these issues for their whole lives.

Next page