Table of Contents

FOR DEVIN

With love and pride

Acclaim for James Reston, Jr.s

WARRIORS OF GOD

James Reston, Jr.... devotes his gift for words to the construction of a thrilling narrative.

The Economist

[A] lively narrative thick with disturbing and provocative details.

Publishers Weekly

A vivid reassessment of the major players in the Third Crusade.

Booklist

Warriors of God... not only puts the reader in the thick of those ancient battles, but also helps the reader understand why East-West tensions remain.

Wisconsin State Journal

Reston offers the reader a captivating story in a lucid and often humorous style.... Warriors of God is a fine example of narrative history.

Library Journal

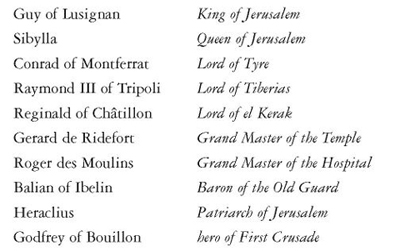

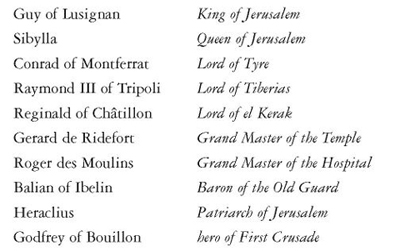

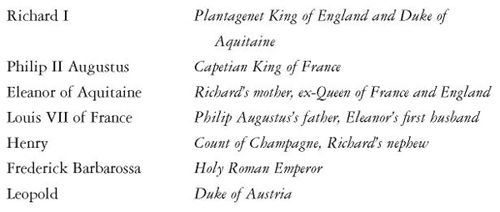

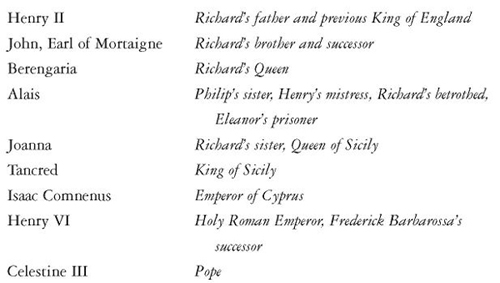

THE PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

CRUSADER KINGDOM OF JERUSALEM

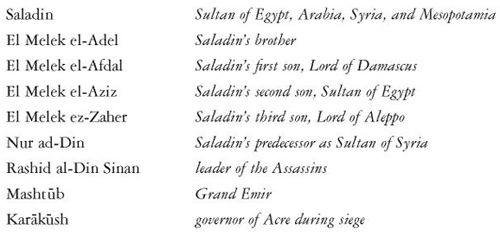

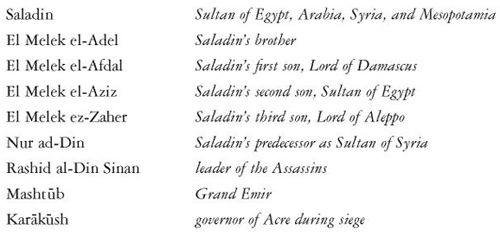

MUSLIMS OF EGYPT AND SYRIA

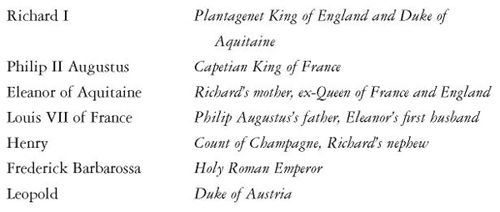

CRUSADERS FROM EUROPE

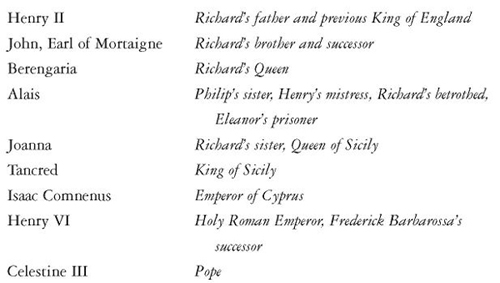

OTHERS

MAPS

.

FOREWORD

The crusader movement, as it is sometimes called, stretched over a period of two hundred years, unleashing a frenzy of hate and violence unprecedented before the advent of the technological age and the scourge of Hitler. The madness was initiated in the name of religion by a Pope of the Christian Church, Urban II, in 1095 as a measure to redirect the energies of warring European barons from their bloody, local disputes into a noble quest to reclaim the Holy Land from the infidel. Once unleashed, the passion could not be controlled. The violence began with the massacre of Jews, proceeded to the wholesale slaughter of Muslims in their native land, sapped the wealth of Europe, and ended with an almost unimaginable death toll on all sides. Bernard of Clairvaux, the great propagandist of the Second Crusade, would lament that he left only one man in Europe to comfort every seven widows.

There were five major crusades (and a handful of minor eruptions bred of the same instinct). Only the First Crusade was successful, in the sense that it managed to capture Jerusalem and in the process make the streets of the Old City run ankle deep with Muslim and Jewish blood. All the others were failures. Three of the five got close to the object of the enterprise, the Holy City. Only because of the disunity of the Arab world did the First Crusade succeed in capturing Jerusalem. Precisely because of the unification of Egypt and Syria into a united Arab empire, the Third Crusade failed to capture it. In the Fifth Crusade, Frederick II of Germany negotiated his way into the Holy City, only to leave Palestine weeks later, pelted with garbage by his own people.

The Third Crusade, spanning the years 118792, is the most interesting of them all. It was the largest military endeavor of the Middle Ages and brought the fury of the entire crusading movement to its zenith. Perhaps most important, it brought two of the most remarkable and fascinating figures of the last millennium into conflict: Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt, Syria, Arabia, and Mesopotamia; and Richard I, King of England, known as the Lionheart.

That conflict of giants in a grand holy tournament still resounds in the modern history and modern politics of the present-day Middle East. Indeed, its resonance is even broader: with conflicts between Christians and Muslims wherever they may exist in the world, from Bosnia to Kosovo to Chechnya to Lebanon to Malaysia to Indonesia.

Until this day Saladin remains a preeminent hero of the Islamic world. It was he who united the Arabs, who defeated the Crusaders in epic battles, who recaptured Jerusalem, and who threw the European invaders out of Arab lands. In the seemingly endless struggle of modern-day Arabs to reassert the essentially Arab nature of Palestine, Saladin lives, vibrantly, as a symbol of hope and as the stuff of myth. In Damascus or Cairo, Amman or East Jerusalem, one can easily fall into lengthy conversations about Saladin, for these ancient memories are central to the Arab sensibility and to their ideology of liberation. On the bars of the small, dimly lit cell in the Old City of Jerusalem where Saladin lived humbly after his grand conquests is the inscription, Allah, Muhammad, Saladin. God, prophet, liberator. Such is Saladins relation to the Muslim God.

The Arab world, it seems, is forever waiting for another Saladin. At Friday prayer, from Aleppo to Cairo to Baghdad, it is not unusual to hear the plea for one like him to come and liberate Jerusalem. His total victory over the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin is held up today as the everlasting symbol of Arab triumph over Western interference. In Damascus, near the entrance to the central Souq al-Hamadiya, a heroic equestrian statue of Saladin graces the main plaza of the city. When protests take place, as they did recently over the renewed negotiations between Israel and Syria about disputed lands, the gathering place is Saladins heroic statue. In the office of the late president of Syria, Hafez Assad, an epic painting of the Battle of Hattin covered an entire wall, and Assad was fond of taking Western visitors over to it, as if to say that just as another Saladin will someday come again, so someday there will also be a second Battle of Hattin. Assads death and funeral in June of 2000, when tens of thousands of Arabs filled the streets of Damascus, provided a pale reflection of what Saladins funeral must have been like in March of 1193.

But it is not only for his military prowess that Saladin is venerated. He is also remembered for his humility, his compassion, his mysticism, his piety, and his restraint.

Next page