To my Fathers memory

First published in Great Britain in 1976

Published in 2007 and reprinted in this format in 2010 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Geoffrey Hindley, 1976, 2007, 2010

ISBN 978 184884 203 8

eISBN 9781848849228

The right of Geoffrey Hindley to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England by the MPG Books Group

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

List of Plates

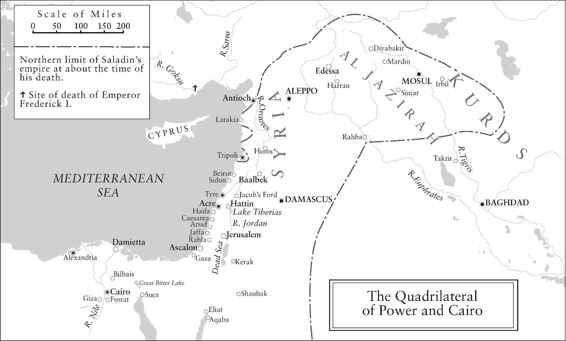

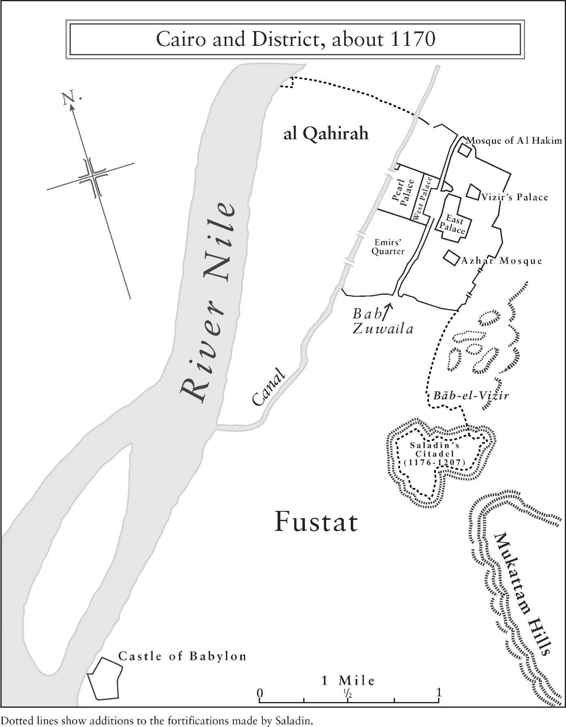

Maps

Introduction

Saladin is one of those rare figures in the long history of confrontation between the Christian West and the world of Islam who earned the respect of his enemies. This alone would make his life worth investigating. For the English-speaking world at least his name is firmly bracketed with that of Richard I the Lionheart, in a context of romantic clichs which form one of the great images of the medieval world of chivalry. The identification began during the lives of the two men and has continued down to the present. Of the two we know very much more about the Muslim hero than about his Christian rival, thanks to the eulogising biographies of his secretary Imad-ad-Din al-Isfahani and his loyal minister Baha-ad-Din, the numerous but more critical references to him in the Historical Compendium of Ibn-al-Athir (11601233), the greatest historian of his time, and detailed treatment of aspects of his career in other contemporary Muslim sources. Of these three, the first two began their careers in the service of Selchk Turkish princes who represented the ruling establishment that Saladin was to displace, while the third, although he remained loyal to the Selchk dynasty of Zengi and regarded Saladin as a usurper, was too honest and objective a man to deny his great qualities.

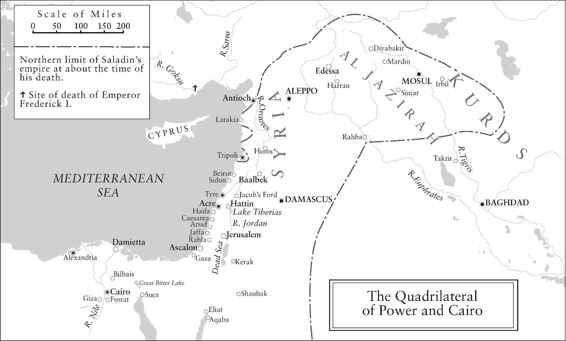

And this brings us to the second fascinating focus of Saladins career. His father, Aiyub, rose high in the service of Zengi and then of his son Nur-ad-Din, but as a Kurd in a Syrian world then ruled by Turkish dynasties he could hardly hope to win the supreme power. The fact that his son did so is one of the greatest tributes to his abilities and was an unforgivable act of presumption in the eyes of the old-school Turkish officials. After the death of Nur-ad-Din in the year 1174 Saladin was to force his claim to suzerainty throughout Turkish Syria, from Mosul to Damascus, and in his last years was the acknowledged arbiter of the rivalries among the descendants of the great Zengi. For die-hards it was bitter proof of the decadence of the world, epitomised in a story told to Ibn-al-Athir by one of his friends. In the autumn of 1191 the Zengid prince Moizz-ad-Din had come to Saladin to beg his mediation in a family land dispute. When the young man came to take his leave of the great king, he got down from his horse. Saladin did the same to say his farewells. But when he prepared to mount his horse again, Moizz-ad-Din helped him and held the stirrup for him. It was Ala-ad-Din Khorrem Shah, son of Izz-ad-Din prince of Mosul (another Zengid), who arranged the robes of the sultan. I was astonished. Then Ibn-al-Athirs friend concluded his horrified account with an invocation. Oh son of Aiyub, you will rest easy whatever manner of death you may die. You for whom the son of a Selchk king held the stirrup.

To hold the stirrup was one of the most potent symbols of submission throughout the contemporary world, Christian West as well as Muslim. Admiring contemporaries noted when a pope was powerful enough to exact such tribute from an emperor. Yet it is surely remarkable that after a decade in which he had ruled from Aleppo to Cairo and had led the armies of Islam in the Holy War against the Infidel, Saladins Kurdish ancestry and his triumph over the disunited Zengids still rankled with his opponents. When the great ruler died his doctor noted that in his experience it was the first time a king had been truly mourned by his subjects. His justice and gentleness were recognised by all those who came into contact with him, but his success was jealously watched by the caliphs of Baghdad, nominal heads of the Islamic community, and dourly resisted by the Zengid rulers he eventually overcame. Seen from the West Saladin was the great champion of the jihad in succession to Nur-ad-Din; to his opponents in Syria his espousal of the Holy War seemed an impertinent usurpation. The Third Crusade, which came so close to recovering Jerusalem for Christendom, drew its contingents from France, Germany and England to oppose it Saladin had only troops from the territories he had forced to acknowledge him.

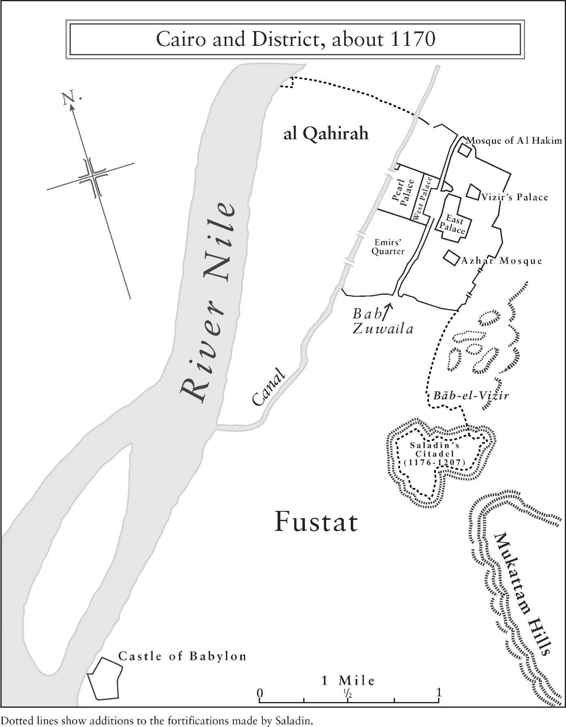

But despite the jealousy and opposition he provoked in the Islamic community there were few, even among his enemies, who denied Saladins generosity, religious conviction and evenness of temper. There were those who accused him of assumed piety for political reasons, but then both Zengi and Nur-ad-Din had had such charges levelled against them. It may be that Saladins strict observance of orthodox Sunnite Islam was in part caused by the wish to emulate the dour and extreme religiosity of Nur-ad-Din. His treatment of his Jewish subjects offers a good illustration of his meticulous adherence to the letter of Islamic law. Before he came to power in Egypt as vizir in 1169 the Shiite caliphs of Cairo (considered heretics by Baghdad) had often used Jewish and Christian advisers in preference to their Sunnite Muslim subjects. In consequence they had relaxed some of the restrictions on non-believers. Saladin reimposed many of these regulations, such as the one that forbade Jews from riding horses. But he scrupulously upheld their right to present petitions for the redress of wrongs under the law and their right to have disputes between Jews tried by Jewish judges as in former times.

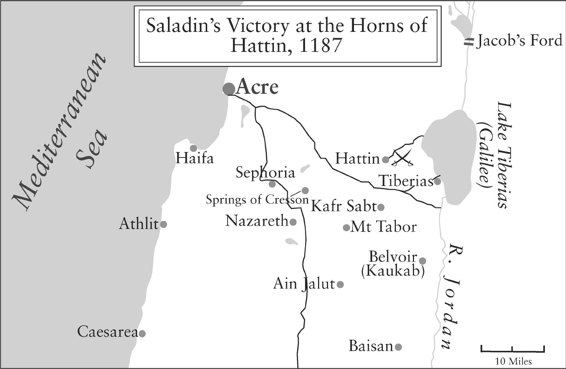

Saladins genuine if legalistic tolerance in religious matters is confirmed by the German Dominican Burkhard, who visited Egypt in 1175 and observed that people there seemed free to follow their religious persuasions. To the Jews indeed Saladins later career seemed to foreshadow great things. The 1170s and 1180s were a period of strong Messianic hopes and Saladins crushing victory over the Christians at the battle of Hattin in 1187 seemed to herald marvellous things to come. A modern biographer of the great Jewish philosopher Maimonides even suggested that his digest of the law, the Mishna Torah, may have been written as the constitution of the new Jewish state then being predicted. When Saladin proclaimed the right of Jews to return to Jerusalem and settle there after his conquest of the city at least one observer, Yhudahal-Harizi, compared the decree to the reestablishment of Jewish Jerusalem by the Persian emperor, Cyrus the Great.

Next page