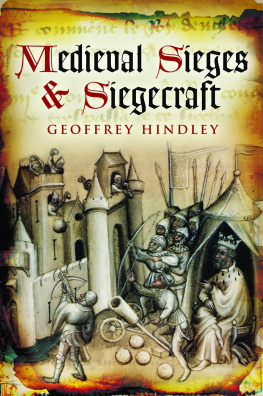

Geoffrey Hindley - Medieval Siege and Siegecraft

Here you can read online Geoffrey Hindley - Medieval Siege and Siegecraft full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Pen & Sword Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Medieval Siege and Siegecraft

- Author:

- Publisher:Pen & Sword Books

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Medieval Siege and Siegecraft: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Medieval Siege and Siegecraft" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Medieval Siege and Siegecraft — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Medieval Siege and Siegecraft" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

T he various narrative accounts of sieges which make up the bulk of the text have been drawn largely from the books on my shelves, with the occasional visit to the Cambridge University Library, whose staff, as always, I would like to thank for their helpfulness. I would also like to thank here my editor, Rupert Harding of Pen & Sword Books, and my copy-editor, Elizabeth Stone, for their useful comments and encouragement. My special thanks are due to Mr Gordon Monaghan for the line drawings credited to him in the captions.

Many authors and their works are acknowledged in the text, while details of publication will be found in the bibliography. I thought it might also be useful to bring together, chapter by chapter, some of the principal sources that contributed to the story: these will be found at the end of the text, in the Notes on the Sources.

These notes are based on the edition and translation of Epitoma rei militaris by Leo F. Stelten (New York, 1990).

The text known as the Rei militaris instituta or Epitoma Rei Militaris (The Handbook of Military Matters) among other titles, probably written about the year AD 400, survives in various medieval manuscripts of various dates, with slight variations of title. The author, the illustrious Flavius Vegetius Renatus, is concerned with the decline, as he saw it, of the imperial Roman army and his recipes for reform of the military structure to be based on a revival of the legion. However, he surveyed all aspects of warfare, tactics and strategy and siege.

Vegetius, as he is commonly known, also provided the basis for other writers on warfare notably Egidio (Aegidia) Colonna (d. 1316); Christine de Pisan, the celebrated French writer on numerous topics; and even Machiavelli (d. 1527) who drew heavily on Vegetius for his own Arte della Guerra .

The Epitoma , or at least a version of it, first appeared in English published by William Caxton in 1486 as The Booke of Fayttes of Arms and Chivalrye , a translation of de Pisans famous work Le Livre des Faits dArmes et de Chevalerie .

Vegetius text also provided the inspiration for a number of sets of illustrations, in fact artists impressions or attempted reconstructions based on the authors not always clear descriptions of machines of war he either knew of from personal experience or had heard reports of. These illustrations, some fanciful, all speculative, provided the basis of various theories or assertions about Roman military apparatus.

This appendix notes principal points made by Vegetius on siege warfare and other observations on warfare in general.

Chapter 12 : concerning the initial attack on a fortress or city. The attacker can expect the greater losses; accordingly, he aims to intimidate by display of arms and martial trumpet calls and then moves the scaling ladders against the walls. Inexperienced defenders may well surrender, but if the assault is repelled by an experienced garrison then the morale of the populace will be increased.

Chapter 14 : concerning a testudo. Vegetius describes here a wooden structure covered with leather and goats fleeces (soaked in water, presumably) so as to be proof against fire lances and arrows. Inside is a beam which may be fitted with an iron hook with which to loosen the masonry or shod with iron and called a ram because it swings back and forth in the manner of a battering-ram. But it takes its name from the tortoise, because just as that beast retracts its head within its shell and then thrusts forward, so the machine vibrates its head back and forth against the stonework.

Chapter 16 : describes musculi , which according to the description are protective wheeled sheds (the cats of medieval military men), better termed pilot fish if we are to retain the marine imagery because they advanced ahead of the siege-tower, like pilot fish ahead of a whale) protecting work parties detailed to fill in the moat.

Chapter 17 : De turribus ambulatoriis (mobile towers). According to Vegetius in earlier Roman times these structures could be from 30ft to 50ft square at the base and so high as to overtop not just the walls but even the turrets above them. They had several levels and might have bridges protected by tunnel-like structures of twigs and branches. The topmost stage of the tower would be manned by bowmen and troops called contati (contact men?) armed with pikes with which they cleared the defenders from the wall by direct contact.

Chapter 18 : ways to destroy such towers include sortie by a fire detail; the use of fire darts hurled by missile throwers; by commando troops let down on ropes from the city walls at night with covered lanterns to set fire to the structure.

Chapter 19 : defenders may raise the height of the wall at the point where the siege-tower is aimed. Vegetius answer to this was to construct a siege-tower with a telescopic stage, which is sunk within the tower until the last moment when it is hauled up by ropes and pulleys to overtop the wall or its height extension. Whether such telescopic towers ever were actually deployed is doubtful.

Chapter 20 : describes a defence against a siege-tower by tunnelling out from the walls once it was clear along which route the tower was to be advanced; when it reached the head of the tunnel it would sink under its own weight.

Chapter 21 : deals with the hazards of troops on scaling-ladders and attributes the invention of this mode of assault to Capaneus, an obscure hero from ancient Greek mythology whose name can have meant very little to a medieval commander. It also describes a swing bridge attachment to a siege-tower which is lowered onto the enemy wall by pulleys at the last moment and another type of bridge thrust out from the tower.

Chapter 22 : describes the ballista , a type of mounted crossbow strung with ropes made of animal sinews and which requires specially trained operatives, and the onager . The Latin means wild ass and this machine, also powered by multiple sinew cordage, Vegetius reckons the most powerful of the stone-throwers. Vegetius says nothing about how the thing actually worked; perhaps it was powered by the torsion of the twisted sinews being suddenly released.

Chapter 24 : describes two types of mining operation (alluding again to the mining industry of the Thracians, presumably the Bessi, a people of north-eastern Thrace a region known for its mine workings), first, the piercing of tunnels under the walls through which assault parties may penetrate the town; second, the incendiary mine beneath the foundation of the walls to collapse them.

Chapter 26 : describes the manoeuvre of faked retirement by the besieging force. The ruse was used at Antioch in 1198 and on numerous other occasions.

Chapter 30 : how to arrive at the specifications for scaling-ladders and siege-towers. One method of measuring the height was to fire an arrow, with string attached, to the top of the battlements (presumably from as near the base of the wall as possible). A second method was to measure the length of the shadow cast by the wall and compare it with shadow cast at the same time by a rod of known length.

Vegetius ends this part of his summary of machines and manoeuvres in land warfare by re-emphasizing that no amount of skill or apparatus can save a fortress that has not been properly provisioned.

Chapter 11 : a legion had carpenters and other artisans in wood working as well as masons and blacksmiths, who could be employed in building winter quarters or making machines of war and wooden (siege-) towers. They even had miners skilled like the Bessi (Henry V of England, one remembers, used professional miners from the Forest of Dean for tunnelling operations against the walls of Harfleur).

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Medieval Siege and Siegecraft»

Look at similar books to Medieval Siege and Siegecraft. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Medieval Siege and Siegecraft and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.