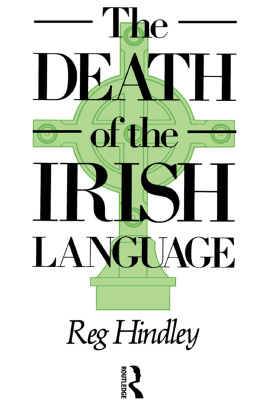

The death of the Irish language

Using a blend of statistical analysis with field surveys among native Irish speakers, Reg Hindley explores the reasons for the decline of the Irish language and investigates the relationships between geographical environment and language retention. He puts Irish into a broader European context as a European minority language, and assesses its present position and prospects.

Reg Hindley, who has been researching into minority languages for many years, is Senior Lecturer in Geography in the Departments of European Studies and Environmental Science at the University of Bradford.

Bradford Studies in European Politics

Local Authorities and New Technologies: The European Dimension

Edited by Kenneth Dyson

Political Parties and Coalitions in European Local Government

Edited by Colin Mellors and Burt Pijnenburg

Broadcasting and New Media Policies in Western Europe

Kenneth Dyson and Peter Humphreys: with Ralph Negrine and Jean-Paul Simon

Combating Long-term Unemployment: Local/EC Relations

Edited by Kenneth Dyson

The death of the Irish language

A qualified obituary

Reg Hindley

First published 1990

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc.

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

New in paperback 1990

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

Copyright 1990 Reg Hindley

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Hindley, Reg, 1929-

The death of the Irish language: a qualified obituary.

1. Irish language

I. Title

491.62

ISBN 0-415-04339-0

0-415-06481-3 (Pbk)

978-1-13508-419-6 (ePub)

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

Hindley, Reg, 1929-

The death of the Irish language: a qualified obituary/Reg Hindley.

p. cm. (Bradford studies in European politics)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-415-04339-5

0-415-06481-3 (Pbk)

1. Irish language History. 2. Irish language Revival. 3. Linguistic minorities Europe. I. Title. II. Series.

PB1215.H5 1990 89-10933

To those who work to keep Irish a living language

Oh the shame of Irish dying in a free Ireland

(unattributed)

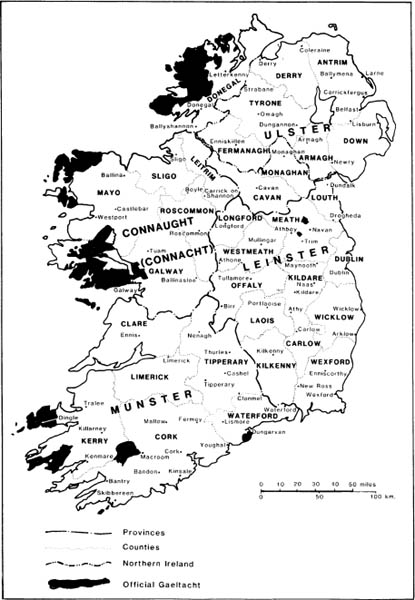

Map 1 Ireland: provinces, counties, principal towns. The Gaeltacht as 1987

Contents

List of tables

List of maps

| Ireland: provinces, counties, principal towns. The Gaeltacht as 1987 |

A note on place-names

The following guidelines have been applied to the presentation of place-names in the text:

The names of Irish-speaking Gaeltacht places are on first use given in Irish with an anglicized equivalent, but thereafter only in Irish unless far removed in the text. This also applies to Gaeltacht places with moderate Irish-speaking minorities. The use of the Irish forms is felt appropriate because (1) they alone represent the correct form (and often meaning) in the language to which the name belongs; (2) any further reading or research will demand acquaintance with the Irish forms, if any venture is made into Irish-language sources; (3) the language is dying and the correct forms of Gaeltacht names are often elusive, even to Irish speakers. They should therefore be recorded and used while they are still current. The anglicized equivalents of most names provide a rough but serviceable guide to the popular native Irish pronunciation. Where the anglicized equivalent is itself unpronounceable except to the initiated e.g. Iveragh, which is pronounced eev-raa I have attempted a passable approximation of my own, to assist the reader.

The names of nominally Gaeltacht places where little Irish is in everyday use are given in English, except in contexts where the Irish version is appropriate, as when using material from Irish-language sources.

County names are usually given in their English forms because they are internationally familiar and no county is mainly or substantially Irish-speaking; but in the regional survey and the tables they are given bilingually because the emphasis there is on Irish language survival in each county and it is therefore appropriate to indicate the Irish forms, which of course are the originals from which the English names derive.

Gaeltacht district names such as Corca Dhuibhne (Corkaguiny) and Diche Sheoigheach (Joyces Country), Gaoth Dobhair (Gweedore), and Iorras (Erris) are used in their Irish forms, with the English equivalent provided on first use.

Directional indicators such as north or west are in English only, except where it is intended to indicate the full Irish-language name for a district. In such cases the English version will also normally be given to maintain clarity of meaning.

Appendices three and four provide bilingual indices of the Irish and English names of current Gaeltacht national schools and district electoral divisions, arranged in county and Gaeltacht order more or less from north to south. These will usually be the forms employed in the text but in cases of conflict appendix three has precedence for greater accuracy in Irish orthography.

Appendix two provides a fuller outline of problems encountered in the rendering and identification of Gaeltacht place-names.

Preface

This book is written by a geographer with a central interest in language and the manifold factors which combine to determine and influence language distributions. He began work on the border-lands of the Welsh language in 1949 and extended this to Irish and Scottish Gaelic in 1956 when he conducted his first field survey in north-west Scotland. An exploratory field investigation of most of the surviving areas of native Irish speech followed in 1957, at much the same time that the official boundaries of the Gaeltacht (the legally defined Irish-speaking districts) were being redrawn. It was already clear that the new boundaries were generous in including within them many areas in which Irish was very little used, and the difficulties of boundary definition in conditions of language change and political sensitivity feature prominently in the work which follows.

Supervision of undergraduate field courses in later years involved detailed studies in north-west Donegal and in the Meath Gaeltacht colonies, and in 1987 the generous grant of study leave by the University of Bradford made possible a repetition and elaboration of the comprehensive survey undertaken thirty years earlier, before all the changes brought about in the wake of the advent in the Gaeltacht of universal secondary education, television, the near-universal private motor car, electricity in every home, piped water, and a revolutionary degree of access to employment in modern light industries. Given this list, a perceptible weakening of the Irish language over the intervening years is only to be expected and some surprise may be permitted that it still survives at all in normal everyday use.