BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Defenders of the Holy Land: Relations Between

the Latin East and the West, 11191187

(1996)

The First Crusade: Origins and Impact

(1997, editor)

The Second Crusade: Scope and Consequences

(2001, coeditor)

The Crusades, 10951197

(2002)

The Experience of Crusading: Volume 2

(2003, coeditor)

The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople

(2004)

The Second Crusade:

Extending the Frontiers of Christendom

(2007)

For my parents

CONTENTS

12

INTRODUCTION

C hristianity versus Islam; crusade against jihad. Blood and dust; withering, shimmering heat; the ring and scrape of metal on metal: some of the sights, sounds, and sensations we imagine to represent the age of the crusades, an epic clash between two of the worlds great religions and a struggle in which men and women fought and died for their faith. Yet this familiar tale does not tell the complete story. This book, which is aimed squarely at the general reader or those looking for an overview of the subject, will, of course, explore this conflict of ideas, belief, and culture. But it will also show the myriad contradictions and the diversity of holy war: friendships and alliances between Christians and Muslims; triumphs of diplomacy rather than the sword; the launch of crusades against Christians, and calls for jihads against Muslims. Taken as a whole, this rich, multifaceted relationship has the capacity to produce a more evocative and insightful account than the usual tales of ChristianMuslim bloodshed alone.

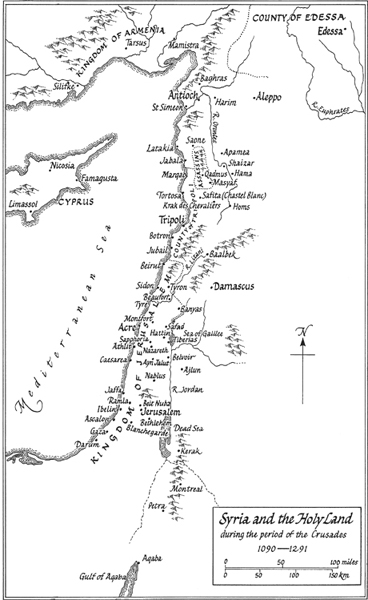

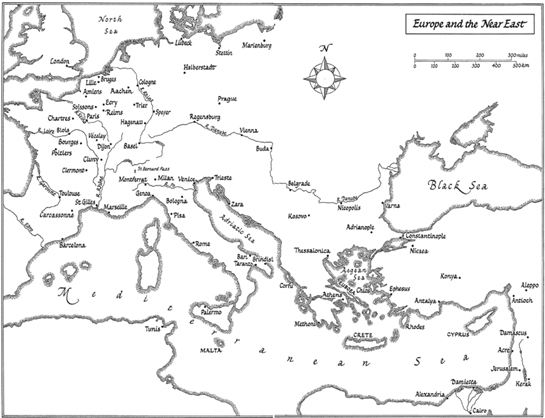

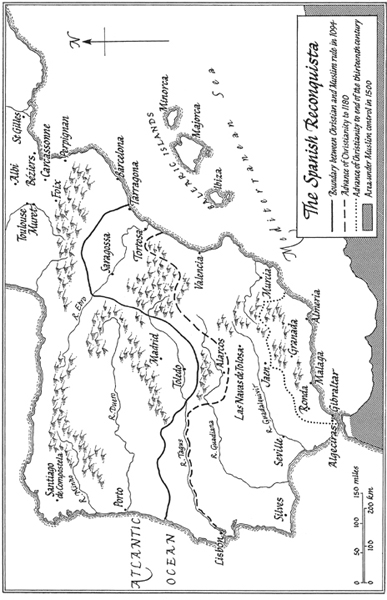

More than nine hundred years ago, Pope Urban II triggered the First Crusadeone of historys great turning points. On November 27, 1095, he urged the knights of France to regain Jerusalem from Muslim hands in return for a spiritual reward. In doing so, Urban unleashed religious warfare on an unprecedented scale and propelled these two great faiths into a conflict of unimagined intensity, the repercussions of which are still felt today. Four years after this speech, the crusaders slaughtered their way into Jerusalem and took possession of the holy city. The conquerors set up the Crusader States in the Near East, but in 1187 Saladin led the armies of the jihad, the Muslim holy war, to victory and drove the Christians back to the eastern Mediterranean coast; just over a hundred years later, the Mamluks of Egypt completed his work and finally ejected the crusaders from the mainland. In the meantime, however, the idea of crusading, that is, fighting to liberate Christian lands and Christian peoples for a spiritual reward, hadin tandem with myriad other influencesexperienced a dramatic geographical and ideological expansion, and this, as we shall see, enabled it to survive in a variety of forms for centuries to come.

Large sections of this book are character-driven. Like many readers, I suspect, the irresistible allure of one of historys great double acts, Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, drew me into the subject as a student and from this developed an interest in the motives and the ideologies of the protagonists. Evidence from contemporary writings, such as chronicles, songs, sermons, travel diaries, letters, financial accounts, and peace treaties, along with visual material from art, architecture, and archaeology, provides a profusion of voices and images that enables us to reconstruct the age of the crusades. Although there is a narrative thread here, this is not a detailed, chronological history of the subject: that is one purview of the academic textbook.

I have chosen to bring to life a variety of figures and events outside of those well known to a general audience. It remains essential to describe the unexpected victory of the First Crusade; the titanic tussle between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin; the breathtaking navet of the Childrens Crusade, and the brutal and crafty suppression of the Knights Templar, but the lives of others can illuminate the age of the crusades just as well: soon after the First Crusade, for example, a fiery jihad preacher, Ali ibn Tahir al-Sulami, exhorted the citizens of Damascus to holy war but his message was decades ahead of mainstream opinion and his early audiences numbered only a handful; Queen Melisende of Jerusalem was an intimidating and astute politician who dominated the kingdom of Jerusalem during the mid-twelfth centuryyet the idea of a woman ruling the most war-torn area of Christendom seems inherently counterintuitive. Frederick II of Germany was an Arabic-speaking Holy Roman Emperor who retook Jerusalem in 1229 without striking a blow, but at the same time he was under a ban of excommunication from the pope; during the late fourteenth century, Henry Bolingbroke (many years before he became the paranoid and brutal King Henry IV of England) behaved as a pilgrim and holy warrior, intent upon creating a chivalric reputation for himself in northern Europe and the Holy Land.

The motives of crusaders have long intrigued historians, and, self-evidently, faith lies at the heart of holy war. From a modern-day western perspective, extreme religious fervor is often synonymous with the fanaticism of minorities, but in the Europe of the central Middle Ages crusading was regarded as virtuous and positive. It was a society saturated with religious belief in which faith provided the template and the boundaries for almost every aspect of behavior and where recognition of divine will and fear of the afterlife were universal. The fight against the enemies of God offered people a way to evade the torments of hell and this is one reason why crusading became a fundamental feature of medieval life. Everyone from emperors, kings and queens, bishops, dukes, and knights, down to peasants and prostitutes, took part in crusades; they were, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries at least, a totally mainstream activity, accepted and endorsed by an entire culture and not, as later became the case, simply the preserve of the noble elite.

But religion was not the sole driving force for crusaders. Part of the fascination with the crusading age, and one theme in this book, is to see how other ideas, such as the lure of land and money, a sense of honor and family tradition, a desire for adventure, and the obligation of service, all sat alongsideand sometimes smotheredreligion. Given the impossibility of ascribing precise motives to any individual from this distance in time we have to weigh the available evidence and point to trends and probabilities. The actions of most crusaders were shaped by multiple, overlapping reasons, and behavior that may seem contradictory to us was not always viewed as such. When, therefore, crusaders from the mercantile powerhouse of Genoa defeated Muslims and, at the same time, secured a profit for their city, they interpreted their success as a sign of divine approval. In other words, in these circumstances, they comfortably assimilated a close link between money and holy war. Likewise, there was a complex relationship between chivalry and crusading. By the mid-thirteenth century the knightly code had become the quintessential basis of noble life and the pursuance of fame and heroic deeds wasif performed in Gods namethe pinnacle of chivalric achievement rather than, as it can appear to us, purely an exercise in ego-building. Economic motives and military excess could, in some cases, dominate or distract crusading expeditions and, on occasion, this provoked intense criticism. The question of motivation shimmers and shifts across time and space, and trying to trace it is part of the challenge and the excitement of this subject.