First published 2008 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2008 by the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East. Conference (6th : 2004: Istanbul, Turkey)

The Fourth Crusade: event, aftermath, and perceptions: papers from the Sixth

Conference of the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East,

Istanbul, Turkey, 25-29 August 2004. - (Crusades. Subsidia)

1. Crusades - Fourth, 1202-1204 - Congresses 2. Military history, Medieval - Congresses

I. Title II. Madden, Thomas F.

949.503.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East. Conference (6th : 2004 : Istanbul, Turkey)

The Fourth crusade : event, aftermath, and perceptions : papers from the Sixth

Conference of the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East,

Istanbul, Turkey, 25-29 August 2004 / edited by Thomas F. Madden.

p. cm. - (Crusades subsidia)

Contributions in English, French, and Italian.

ISBN 978-0-7546-6319-5 (alk. paper)

1. Crusades - Fourth, 1202-1204 - Congresses. 2. Military history, Medieval - Congresses.

I. Madden, Thomas F. II. Title.

D164.S63 2004

949.503-dc22

2007016269

ISBN 9780754663195 (hbk)

ISBN 9781138249653 (pbk)

Typeset by N2productions

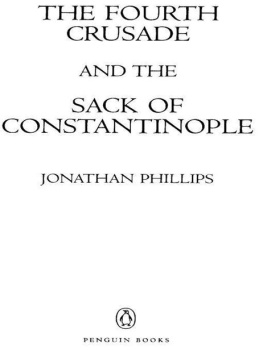

It is an irony that of the major numbered crusades the First and the Fourth have attracted significantly more scholarly attention than any others. Interest in the First Crusade is natural enough. It was the beginning of a movement that endured for centuries and fundamentally shaped Europe and its place in the Mediterranean world. But the Fourth Crusade cannot make that claim. Instead, it was an enterprise launched during the maturity of the movement that proceeded to go terribly wrong. Organized to restore Jerusalem to Christian control, the Fourth Crusade conquered and looted the greatest Christian city in the world. The story of how that came to be is a tangled web of conflicting agendas, passions, imperatives, and desires. It is the extraordinary outcome of the Fourth Crusade, which even contemporaries believed could only be an act of God, that draws curious investigators to attempt to unlock its secrets. Indeed, in that respect it is very like the First Crusade.

Western scholars may approach the Fourth Crusade as a fascinating puzzle or an intriguing historical event, yet for others it remains an open wound. Steven Runciman famously wrote that there was never a greater crime against humanity than the Fourth Crusade and this view is still current today in parts of the world. For example, when the Greek government invited Pope John Paul II to Athens in 2001, large numbers of Orthodox monks, nuns, and priests protested the arrival of what some of them called the two-horned monster of Rome. When the pope landed on May 4, not a single member of the Orthodox clergy came to the airport to greet him. Thousands of them, however, took to the streets, wrapped in Greek flags, demanding that the 80-year-old pontiff be expelled. The pope then paid a courtesy visit to Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens. The archbishop cataloged a list of Orthodox grievances against Rome, including such things as the expansion of eastern Catholic churches and the Vaticans attitude toward Cyprus. Pride of place, however, was given not to current events, but to the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath. In his welcome address to the pope, the archbishop said:

Understandably a large part of the Church of Greece opposes your presence here These reactions express not only explicit censure of the unacceptable acts of violence perpetrated against concerned Orthodox peoples, but also the demand of Orthodox conscience for a formal condemnation of injustices committed against them by the Christian West. The Orthodox Greek people, more than other Orthodox peoples, sense more intensely in its religious consciousness and national memory the traumatic experiences, that remain as open wounds inflicted on its vigorous body, as is known to all, by the destructive mania of the Crusaders and the period of Latin rule

There can be little doubt that memories and perceptions of the Fourth Crusade, accurate or not, remain powerful even today.

In late August 2004, only a few months after the 800th anniversary of the crusader conquest of Constantinople, the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East held its Sixth International Conference at Bogazii University in Istanbul, Turkey. The theme, Around the Fourth Crusade: Before and After, brought scholars from all parts of the world to present their research. The conference began on 25 August with formal welcomes delivered by Nevra Necipoglu, Sabih Tansal, and Selim Deringil of Bogazii University followed by Michel Balard of the Sorbonne Universitys Presidential Address. I then gave the opening lecture, entitled 1204 and Historical Memory. The next three days were filled with a rich bounty of crusade scholarship. Nearly one hundred papers were delivered, approximately half of which were directly related to the Fourth Crusade. These included plenary lectures by Jonathan Riley-Smith (An Alternative Approach to the Fourth Crusade) and Benjamin Z. Kedar (The Fourth Crusades Second Front). The conference ended on 29th August with a plenary panel discussion on the past and future of Fourth Crusade historiography. The panel, chaired by Benjamin Z. Kedar, consisted of David Jacoby, Jonathan Riley-Smith, Michel Balard, Alfred J. Andrea, and myself.

The papers delivered in Istanbul made starkly clear that approaches to the Fourth Crusade have changed over the years. In the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century, scholarship was preoccupied with the Diversion Question. At issue was whether the Fourth Crusade had diverted from its original destination as a result of a series of accidents, as Geoffrey de Villehardouin explains in his chronicle, or through the machinations of one or more actors, as authors such as Robert of Clari or Nicetas Choniates suggest. By the mid-twentieth century most historians, following Runciman and others, had settled on the Venetians and their doge, Enrico Dandolo, as the villains of this piece. The Venetians, it was said, had cynically joined the crusade as a means of placing Byzantium under their permanent control. The crusaders, blinded by chivalric piety, never suspected that they had been duped until it was too late. It is telling that in almost fifty papers delivered on Fourth Crusade topics in Istanbul in 2004, none took up the Diversion Question. That, at least, appears to be settled.