CAMPAIGN 237

THE FOURTH CRUSADE 120204

The betrayal of Byzantium

| DAVID NICOLLE | ILLUSTRATED BY CHRISTA HOOK |

| Series editor Marcus Cowper |

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

Byzantine wall painting of a warrior saint made in the late 12th or early 13th century, in the monastery church of Panagia Kosmosotira, Feres, on the frontier between Greece and Turkey. (Author's photograph)

If the crusades have become controversial, the Fourth Crusade always was so. Until modern times the idea of Christians and Muslims slaughtering each other in the name of religion seemed almost acceptable, but the idea of Latin Catholic Crusaders turning against fellow Christians of the Orthodox Church shocked many people, even at the time, and came to be described as The Great Betrayal. It was even blamed for so undermining the Greek-speaking Byzantine state that this relic of the ancient Roman Empire succumbed to the Ottoman Turks. In reality the Fourth Crusade was not that straightforward; nor was its aftermath inevitable.

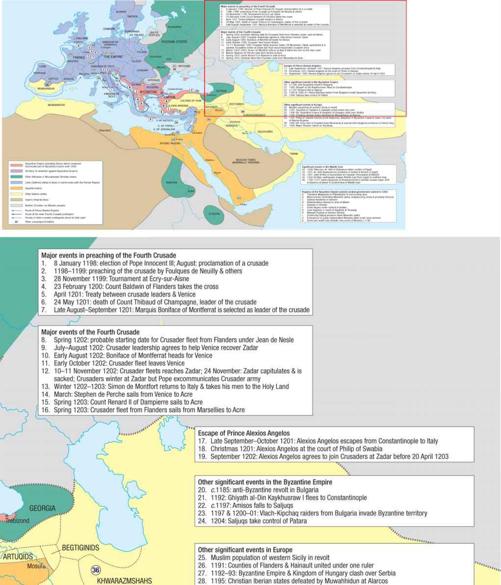

The Fourth Crusade was a consequence of the deeply disappointing though gratifyingly heroic Third Crusade, which had failed to regain the Holy City of Jerusalem from Saladin. On 8 January 1198 a new pope, the hugely ambitious Innocent III, took the reins of power in Rome. In August he proclaimed a new crusade, the declared purpose of which was to liberate Jerusalem from the infidel by invading Egypt, the chief centre of Muslim power in the eastern Mediterranean. It was also the most important sultanate in the Ayyubid Empire founded by Saladin. Those who dreamed of destroying the Islamic Middle East had now recognized that Egypt was the key, but if their strategy was correct then their planning was not. The realities of power, money, climate and the availability of food to sustain a crusading army would cause the greater part of the Fourth Crusade to be diverted against fellow Christians. Its first victim would be the largely Latin city of Zadar (then called Zara); the second would be Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire and the biggest, wealthiest and most cultured city in Christendom.

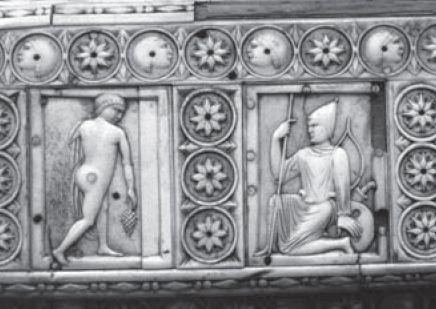

Carved ivory panel showing allegorical figures of Peace and War, Byzantine, 11th12th century. (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. Authors photograph)

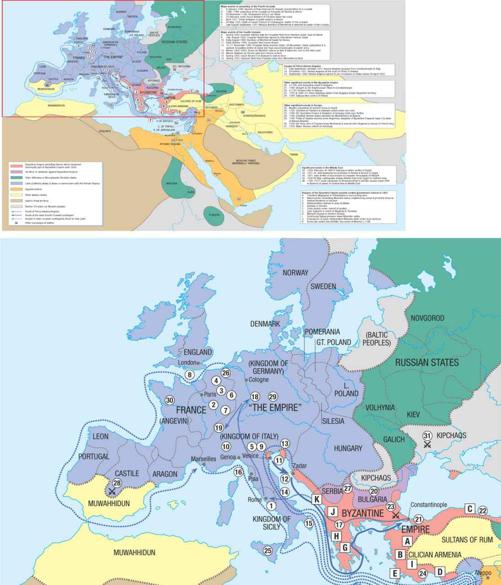

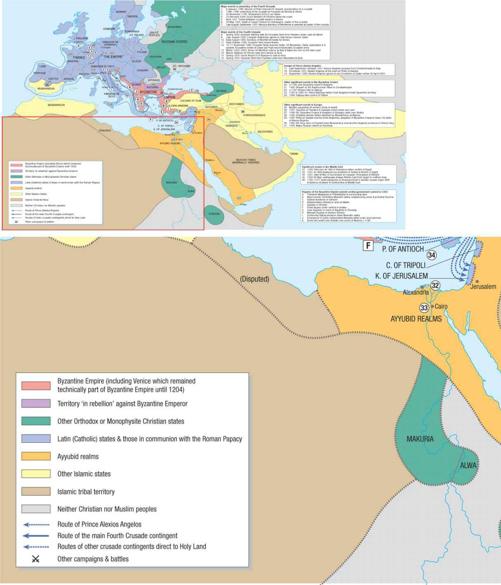

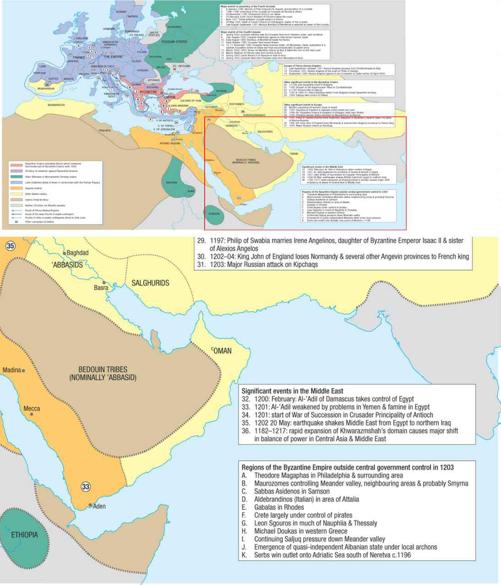

Europe and the Middle East, c .1195

BYZANTIUM AND ITS NEIGHBOURS

Relations between the Orthodox Byzantine Empire and its Latin neighbours had been close but complex for centuries. However, the differences that seem obvious today were not necessarily seen that way at the time. Nor was the Byzantine Empire necessarily a declining power in need of Western help. Under the 12th-century Comnenid dynasty Byzantium appeared a powerful state bent on regaining territory from its Muslim eastern neighbours and from its Christian neighbours in the Balkans, Italy and even central Europe. Meanwhile, in Western Europe a remarkable economic revolution had already started more than a century earlier, yet it was still somewhat backward, warlike and aggressive. One area where Western superiority was already established was at sea, most of the Mediterranean now being dominated by Italian sailors and merchants. Amalfi had been first on the scene and its people had their own distinct quarter in Constantinople, where the Greeks regarded these Amalfitans as being almost as civilized as themselves. Following close behind, and already more powerful than Amalfi, were the merchant republics of Pisa, Genoa and Venice. The former two had a reputation for ferocity, often directed against each other, while the Venetians were theoretically still subjects of the Byzantine Empire, and would remain so until 1204.

Most crusades to the Middle East already relied upon naval power. However, the Fourth Crusade was an entirely maritime expedition, which cannot be understood without some appreciation of early 13th-century Mediterranean nautical knowledge. This was more advanced than is generally realized, the sailors possessing geographical knowledge that would not be written down for centuries. For example, there is strong evidence that simple forms of portolano coastal maps were used at a time when the famous medieval mappe mundi made by monks offered fanciful and entirely useless images of the known world. It is thus highly unlikely that popes and other rulers failed to use such information when planning major military expeditions overseas. On the other hand the merchants, sailors and governments involved in supposedly illegal trade with Islamic powers preferred to remain discreet.

A flanking tower of the Burj al-Gharbi (Western Gate) in Alexandria, which was the original target of the Fourth Crusade. (Authors photograph)

A lance-armed cavalryman pursuing a horse archer was a popular motif in Byzantine art, these being on an engraved late 12th- or early 13th-century bronze bowl. (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

In contrast there was an extraordinary amount of misinformation in Western Europe that exaggerated, though did not entirely invent, the friendly relations between later 12th-century Byzantine emperors and Saladin or his successors. To this were added lurid stories about the supposed weakness, effeminacy and corruption of the Greeks, which reflected the undoubtedly sophisticated and often unwarlike character of the Byzantine ruling elite.

Alongside these negative images of Byzantium there was a dream of LatinByzantine cooperation against the infidel, which had existed for centuries. The ideal appeared in a later 12th-century version in chansons de geste epic poems such as Girart de Roussillon , although here Constantinople is a distant and strange place. Another manifestation is found in the 13th-century Chanson du Plerinage de Charlemagne , which was probably based upon a lost 12th-century or late 11th-century original. Constantinople is again portrayed as an almost magical city, perhaps reflecting fear of Byzantine technology and science.