C OLONIZING C HRISTIANITY

ORTHODOX CHRISTIANITY AND CONTEMPORARY THOUGHT

SERIES EDITORS

Aristotle Papanikolaou and Ashley M. Purpura

This series consists of books that seek to bring Orthodox Christianity into an engagement with contemporary forms of thought. Its goal is to promote (1) historical studies in Orthodox Christianity that are interdisciplinary, employ a variety of methods, and speak to contemporary issues; and (2) constructive theological arguments in conversation with patristic sources and that focus on contemporary questions ranging from the traditional theological and philosophical themes of God and human identity to cultural, political, economic, and ethical concerns. The books in the series explore both the relevancy of Orthodox Christianity to contemporary challenges and the impact of contemporary modes of thought on Orthodox self-understandings.

Copyright 2019 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https://catalog.loc.gov.

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 195 4 3 2 1

First edition

C ONTENTS

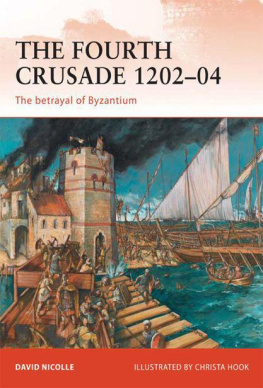

This book began as (and remains) a thought experiment. Its animating question is what happens if we apply the resources of colonial and postcolonial critique to texts about Christian difference that were produced in the context of the Fourth Crusade? It proposes that treating the Fourth Crusade as a colonial experience helps us to understand more fully the ways in which Latin Christians authorized the subjugation of Greek Christians, the establishment of Latin settlement in the Christian East, and the exceptional degree of resource extractionboth material and religiousfrom the region. It also explores in detail the ways in which the experience of colonial subjugation not only transformed the way that Eastern Christians viewed themselves and the Western Christian Other but also how the same experience opened permanent fissures within the Orthodox community, which struggled to develop a consistent response to aggressive demands for submission to the Roman Church. This internal fracturing has done more lasting damage to the modern Orthodox Church than any material act perpetrated by the crusaders.

This book is not a history of the Fourth Crusade. Nor does it propose to be any kind of comprehensive study of Eastern Christian/Western Christian relations during the Middle Ages. In these regards, historiographers are likely to be disappointed. Rather, Colonizing Christianity offers a close reading of a handful of texts from the era of the Fourth Crusade in the hope of illuminating the mechanisms by which Western Christians authorized and exploited the Christian East and, concurrently, the ways in which Eastern Christians understood and responded to this dramatic shift in political and religious fortunes.

Although the book employs methodological resources that might appear unconventional, even esoteric to some readers, the argument of the book is straightforward. Namely, Colonizing Christianity maintains that the statements of Greek and Latin religious polemic that emerged in the context of the Fourth Crusade should be interpreted as having been produced in a colonial setting and, as such, reveal more about the political, economic, and cultural uncertainty of communities in conflict than they offer genuine theological insight. Given that it was in the context of the Fourth Crusadeand not the so-called Photian Schism of the ninth century, the so-called Great Schism of 1054, or any other period of ecclesiastical controversythat Greek and Latin apologists developed the most elaborate condemnations of one another, it behooves historians (and those who care about Christian unity) to investigate anew the conditions that give rise to the most deliberate efforts to forbid Greek and Latin sacramental unity in the Middle Ages and to ask whether those arguments reveal genuine theological insight or simply convey political or cultural animosity in the guise of theological disputation.

The Fourth Crusade: A Very Quick History

There is, of course, no shortage of scholars who have studied the crusades either as a whole or individually.

When Pope Innocent III ascended Peters throne in 1198, he almost immediately began planning for what was supposed to be the largest crusade to date. Whereas many previous expeditions had been bogged down by proceeding along a land route through Central Europe and Byzantium, Innocent and the crusade leaders devised a plan to contract with the Republic of Venice and to set sail for Egypt, hoping to march from Egypt to Jerusalem. This was an expensive undertaking and Innocent did something no previous pope had done, which was to levy a tax against every diocese in the Christian West. But Innocents plans were stymied from the startnot only was he unable to raise the number of soldiers that he had hoped, but he and the crusade leaders also failed to obtain sufficient funding to meet their contractual arrangement with the Venetians. The Venetians refused to acquiesce without payment.

Against Innocents explicit warnings, the Venetians and the crusaders hatched a plan wherein the soldiers would lay siege to the Christian city of Zara (a break-away Venetian colony on the coast of modern-day Croatia) and the Venetians would agree to accept a delayed payment on the debt owed to them. Pope Innocent III had previously demanded that the crusaders not attack any Christian city. Furious with what had happened, Pope Innocent excommunicated the crusade leaders and all of their soldiers and sailors. It looked like the entire project might fall apart.

Meanwhile in Constantinople, in 1195, the Byzantine emperor, Isaac II Angelos was deposed, blinded, and imprisoned by his brother, Alexius III, in a palace coup. Isaacs son, the eventual Alexius IV, managed to escape the city and in 1201 made his way to the West where he took shelter with his sister and brother-in-law, Philip of Swabia, one of the eventual leaders of the Fourth Crusade. Upon his arrival, the younger Alexius, attempted to convince Philip and other Western aristocrats to help him restore his fathers throne. But it was not until the ill-fated expedition to Zara and the uncertainty that it unleashed that Alexius was able to convince the crusade leadership to support his claim in Constantinople. But that support also came with a priceAlexius not only promised the crusade leaders a significant monetary payment, but he also promised to provide soldiers for their eventual attack on Egypt.

Despite the repeated warnings of further papal condemnation, the crusaders arrived on the outskirts of Constantinople in June of 1203. After a few weeks of sparring on the plains outside of the city and at the citys harbor walls, Alexius III took flight in the middle of the night and the Byzantine aristocracy decided to restore the aged and blind Isaac II to the throne. By August, Alexius IV was crowned coemperor and he began the process of paying his debts to the crusaders. Alexius IV soon proved unable to provide everything that he promised and the crusaders grew frustrated with their situation. When Alexius IV was murdered in yet another palace coup, the crusaders decided to take matters into their own hands.

Next page