Ad infinitum

An Empire Lived in Latin

... HVMANITAS VOCABATVR, CVM PARS SERVITVTIS ESSET.

... called "civilization," when it was just part of being a slave.

Tacitus, Agricola, xxi

T HE HISTORY OF LATIN is the history of the development of western Europe, right up to the point when Europe made its shattering impact on the rest of the world. In fact, only seen from the perspective of Latin does Europe really show itself as a single story: nothing else was there all the way through and involved in so many aspects, not Rome, not the Empire, not the Catholic Church, not even Christianity itself.

For the people who spoke and wrote it, the language was their constant companion; learning it was the universal key for entry into their culture; and expression in it was the unchanging means for taking social action. And this relationship with Latin, for its speakers and writers, lasted for two and a half thousand years from 750 BC. There was a single tradition through those millennia, and it was expressedalmost exclusively until 1250, and predominantly and influentially for another five hundred years thereafterin Latin. Romans' and Europeans' thoughts were formed in Latin; and so the history of Latin, however clearly or vaguely we may discern it, is utterly and pervasively bound up with the thinking behind the history of western Europe.

Latin, properly understood, is something like the soul of Europe's civilization. But the European unity that the Romans achieved and organized was something very different from the consensual model of the modern European Union. It was far closer in spirit to the kind of unity that Hitler and Mussolini were aiming at. No one ever voted to join the Roman Empire, even if the empire itself was run through elected officials, and LIBERTAS remained a Roman ideal, ROMANITASthe Roman way as suchwas never something voluntarily adopted by non-Roman communities. Conquest by a Roman army was almost always required before outsiders would come to see its virtues, and knowledge of Latin spread within a new province.

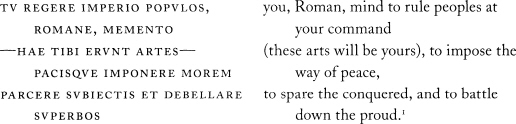

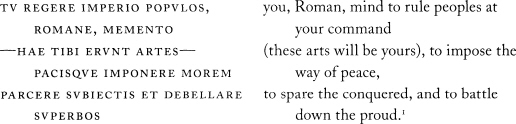

At the outset, the Latin language was something imposed on a largely unwilling populace, if arguablyin the Roman mind, and that of later generationsfor their greater good. There was no sense of charm or seduction about the spread of Latin, and in this it differs from some other widespread languages: consider the pervasive image of Sanskrit as a luxuriant growth across the expanse of India and Southeast Asia, or indeed the purported attractions of French in the nineteenth century as an alluring mistress. Speakers of Latin, even the most eloquent and illustrious, saw it as a serious and overbearing vehicle for communication. In the famous words of Virgil:

EXPOLIA, "Strip him."

The most excellent Flavius Leontius Beronicianus, governor of the The -baid in southern Egypt in the early 400s AD, ruled a Greek-speaking province. Greek had been the language of power there since the days of the Ptolemies more than seven centuries before, but the judicial system over which he presided was Roman. Its official records were kept in Latin, even of proceedings that actually took place largely in Greek and perhaps marginally (and through Greek interpreters) in Egyptian. The record we have, apparently verbatim, is in a mixture of Latin and Greek. Fifteen centuries later, it turned up on an Egyptian rubbish dump.

Slaves called to witness in Roman trials had always been routinely beaten, in theory as a guarantee of honesty; but on this day Beronicianus seems to have been in two minds, EXPOLIA. The governor was speaking Latin, and so the first the witness would have known of what was to happen was when his shirt was taken off him. The governor went on in Greek, "For what reason did you enter proceedings against the councillor?" remarking to the staff officer (also in Greek), "Have him beaten." The record states that the witness was thrashed with ox sinews, and then the governor said in Greek, "Don't beat free men." And turning to the staff, PARCE, "Leave off"

What was it like having your life run for you in Latin? Even after three centuries of Roman rule, Latin stood as a potent symbol of irresistible, and sometimes arbitrary, power, especially to those who did not know the language.

By the nature of things, we do not have many direct accounts of being on the receiving end of government administered in Latin. Our sources are writings that have survived, whether on papyrus and parchment through two millennia of recopying, or on scraps of masonry that have directly defied erosion and decay. And where Latin was dominant, Latin users largely monopolized literacy. We seek almost in vain for non-Latin attitudes to the advent of Latin.

In fact, some of the most vividly subjective statements of the impact of Roman rule and the advent of Latin come from the pen of a man who had held the highest elective office in the Roman state, the historian Cornelius Tacitus. He described the British in the second century as ready to tolerate military service, tribute, and other impositions of empire, up to but not including abuse, "being already schooled to obey, but not yet to accept slavery."

Clearly, the major inconveniences of life under the Empire were taxes and military conscription, and neither was helped by the manifestly arbitrary way that those in charge could abuse their offices. But for many in the first generation to be conquered, the far greater threats were of personal enslavement and deportation, a life made up of all duties and no rights, next to which this "moral slavery" that exercised Tacitus was no slavery at all. This very real prospect, aggravated by the thought that the new recruits would always be the worst treated, was something else that he imagined looming large in the minds of Calgacus and his army of North Britons about to make their last stand against Rome.

On the other hand, once the immovability of the Roman yoke had become established, there were compensations, if only for those nearer the top in their societies.

So language was early seen as one of the benefits of the new dispensation. Later, this enthusiasm threatened to get out of hand: Juvenal, a contemporary of Tacitus' at Rome, commented on the Empire-wide popularity of the Romans' traditional education in rhetoric:

Today the whole world has its Greek and Roman Athens;

the eloquent Gauls have taught the British to be advocates,

and Thule is talking of hiring an oratory teacher.

In the early days, even some Romans bore the linguistic brunt when the spreading PAX ROMANA temporarily outran the sphere of Latin's currency. Ovid was the very model of Roman urbanity, a leading poet and wit in the time of Augustus, HOMO EMVNCTAE NARIS as they would have put it, 'a man with an unblocked nose'. With a divine irony, if not poetic justice, he was exiled in AD 8 to Tomi, a town on the western coast of the Black Sea (modern Constantsa) with less than a generation of Romanization behind it. Evidently, he suffered from the lack of Latin there. There was so little of it that his reputation counted for nothing. Instead, he described rather vividly the typical problems of a visitor who "does not speak the language": "They deal in their own friendly language: I have to get things across through gestures. I'm the barbarian here, uncomprehended by anyone, while the Getans laugh witlessly at words of Latin. They openly insult me to my face in safety, perhaps even twitting me for being an exile. And all too often they believe the stories made up about me, however much I shake my head or nod at their words."

Next page