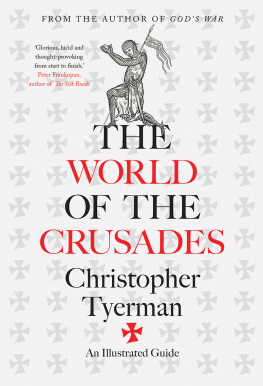

THE WORLD OF THE CRUSADES

Copyright 2019 Christopher Tyerman

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Fournier MT Regular by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceridigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019931656

ISBN 978-0-300-21739-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In Memoriam

J.H.W.M.

CONTENTS

THE CRUSADES IN DETAIL

ILLUSTRATIONS, FIGURES AND MAPS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FIGURES

MAPS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I t is a pleasure as well as duty to thank those who have smoothed the path of this book. The idea for it emerged in conversation with Heather McCallum who has thereafter deftly shepherded the project to completion. The team at Yale, Marika Lysandrou, Rachael Lonsdale and Clarissa Sutherland, have guided production with conscientious accommodating efficiency. As ever, my agent, Simon Lloyd, has proved an effective ally and advocate. Sara Ayad undertook with tenacity and enthusiasm the initial labour of realising the images I had chosen, and Percie Edgeler kindly completed the task. Richard Mason, in copyediting, and Martin Brown, in drawing the maps, supplied vital structural support. The presss three anonymous readers generously took pains to note deficiencies and suggest improvements, saving me from blunders and greatly improving the whole. The remaining errors and misconceptions are mine alone. Any general study exposes its authors limitations perched atop a pyramid of others scholarship. To the alert and interested my own debts will be apparent throughout the text and the notes. The Principal and Fellows of Hertford College, Oxford allowed me important sabbatical research leave at an early stage of preparation. The Ludwig Fund for the Humanities at New College, Oxford generously offered a grant towards the sourcing of pictures. These two colleges have provided enriching academic havens over many years. During the writing of the book, unlucky coincidence saw the deaths of a number of close personal and academic friends and mentors. To the memory of one, for half a century the most generous, effervescent co-conspirator in the human comedy, it is dedicated.

C.J.T., October 2018

PREFACE

T he medieval crusades are both well known and much misunderstood. For almost a thousand years, the startling narratives of disruptive ideological commitment, military conflict and international conquest have excited, disturbed, intrigued and repelled. In mobilising, over many generations, hundreds of thousands of recruits to fight for causes physically distant and emotionally transcendent, the crusades appear extraordinary while simultaneously exposing in sharp relief the psychological and material resources of the distant societies from which they sprang and on which they preyed. With violence in the name of religion no longer appearing as outdated, eccentric or alien as it did only half a generation ago, the crusades persist in giving pause for thought. Yet they were of their time not ours. Modern fascination with the motivating force of religion has tended to simplify the crusades as wars of faith. This misleads most obviously in two ways. It imposes a false binary cohesion on the identities and incentives of the warring parties, as in Christians versus Muslims, when the reality was more confused, cooperative as well as coercive, a matter of contact as well as competition. It also discounts the realities of warfare. Like religion, public violence is social and cultural. Crusaders involvement varied from the devout to the forced, from free choice to the demands of employment, from enthusiasm to indifference to resentment. The crusades were wars fought under the banner of religious belief and are inexplicable without recognising that. However, they were also both more and less than that: more, in that they fitted wider general patterns of cultural and territorial aggression; less, in that, as wars, they were fought like any other, a matter of money and men, tactics and technology, castles and carpentry.

A third misconception is to see the crusades only in the context of a unique concern with the Holy Land. A useful and often effective means to recruit, fund and justify military enterprises across half a millennium of Eurasian history, the crusades operated as part of a material, political and cultural expansion of medieval western Europe, a path of connection and contact as well as alienation and conflict. The crusades did not initiate contacts with the Islamic world, for these had been growing in the decades before the First Crusade through pilgrimages; shared frontiers and conquests in Iberia and Sicily; and, especially, increased commerce, particularly with north Africa. While the original incentive to control Jerusalem and the Holy Land remained the defining inspiration, crusades, as proclaimed by church authorities, were not confined to wars and conquests in the Near East. They contributed to the political re-ordering of Iberia and the radical cultural transformation of the Baltic. Just one aspect of the penetration by western Europeans into the eastern Mediterranean, they played a part in the creation of an idea of distinctive European identity. The ideological legacy extended into the Atlantic and to the Americas while, at home, helping to sharpen intolerance towards social and religious minorities and dissidents. Despite an intrinsic supranational dimension, the crusading mentality of providential exceptionalism and divine favour bled into emerging national identities, sometimes, as with the Danish national flag, visibly so. The crusaders reach straddled continents. Victims included Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Balts, Livs, Spanish Moors, Syrians, Palestinians, Egyptians, Moroccans, Tunisians, Russians, Finns, Bosnians, west German peasants, English rebels, Bohemian nationalists, political enemies of popes in Germany, Italy and Aragon, French and Savoyard dissenters, and Jews. However, the special influence of crusading can be exaggerated. In almost all cases, the crusades formed part of wider processes of engagement, competition and conflict, a makeweight not the pivot. Even the iconic First Crusade to Jerusalem owed its inception to existing western involvement in the Mediterranean and developments in the politics of Asia Minor and the Levant.

Crusades were wars; not all were fought by earnest idealists or for altruistic ideals, or, for that matter, by cynical opportunists. For most involved, their intentions, ambitions and choices were mixed and inevitably constrained by social and economic circumstances, not dictated by unfettered enthusiasm. The world of the crusades was the world of non-crusaders. The gloss of clerical idealism covers much of the surviving evidence with a distractingly coherent sheen. One aim of this book is to peer behind the constructed contemporary images to explore how the ideas and practice of the wars of the cross reflected and influenced the society that produced them. Much continued interest in the crusades has been sustained by the inclination to project current concerns from the allure of religious or ideological warfare to the political fate of Palestine onto the crusading past, paradoxically viewed as simultaneously alien and instructive, a habit that has been around since the Renaissance. The crusades even find themselves corralled into the self-serving unhistorical polemical myth of an immutable clash of civilisations. Yet the crusades do not hold up a mirror to the modern world so much as a window into remote past experience. What follows, therefore, seeks to examine crusading in its own muddied and muddling political, social, economic and cultural setting, not as a dimension of some inevitable cosmic struggle.

Next page