THE WORLD OF THE CRUSADES

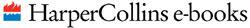

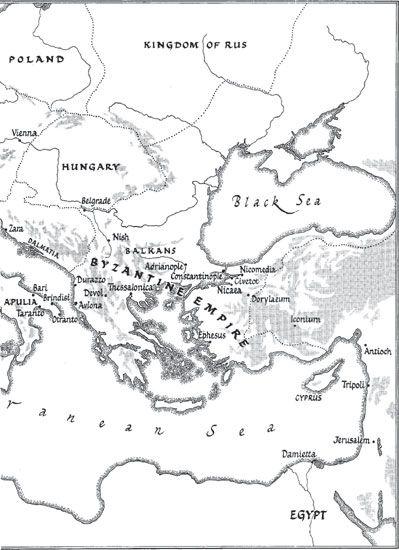

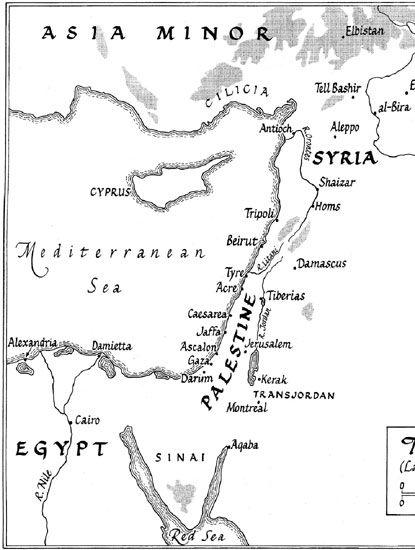

Nine hundred years ago the Christians of Europe waged a series of holy wars, or crusades, against the Muslim world, battling for dominion of a region sacred to both faithsthe Holy Land. This bloody struggle raged for two centuries, reshaping the history of Islam and the West. In the course of these monumental expeditions, hundreds of thousands of crusaders travelled across the face of the known world to conquer and then defend an isolated swathe of territory centred on the hallowed city of Jerusalem. They were led by the likes of Richard the Lionheart, warrior-king of England, and the saintly monarch of France, Louis IX, to fight in gruelling sieges and fearsome battles; passing through verdant forests and arid deserts, enduring starvation and disease, encountering the fabled emperors of Byzantium and marching beside forbidding Templar knights. Those who died were thought of as martyrs, while survivors believed that their souls had been scourged of sin by the tempest of combat and trials of pilgrimage.

The advent of these crusades stirred Islam to action, reawakening dedication to the cause of jihad (holy war). Muslims from Syria, Egypt and Iraq fought to drive their Christian foes out of the Holy Landchampioned by the merciless warlord Zangi and the mighty Saladin; empowered by the rise of Sultan Baybars and his elite mamluk slave soldiers; sometimes aided by the intrigues of the implacable Assassins. Years of conflict inevitably bred greater familiarity, even at times grudging respect and peaceful contact through truce and commerce. But as the decades passed, the fires of conflict burned on and the tide slowly turned in Islams favour. Though the dream of Christian victory lived on, the Muslim world prevailed, securing lasting possession of Jerusalem and the Near East.

This dramatic story has always fired the imagination and fuelled debate. And, over the centuries, the crusades have been subject to startlingly varied interpretations: held up as proof of the folly of religious faith and the base savagery of human nature, or promoted as glorious expressions of Christian chivalry and civilising colonialism. They have been presented as a dark episode in Europes historywhen ravening hordes of greedy western barbarians launched unprovoked, acquisitive attacks upon the cultured innocents of Islamor defended as just wars sparked by Muslim aggression and prosecuted to recover Christian territory. The crusaders themselves have been depicted as both land-hungry brutes and pilgrim soldiers inspired by fervent piety; and their Muslim rivals portrayed as vicious and tyrannical oppressors, ardent fanatics or devout paragons of honour and clemency.

The medieval crusades have also been used as a mirror to the modern world, both through the forging of tenuous links between recent events and the distant past, and via the dubious practice of historical parallelism. Thus, during the nineteenth century the French and English appropriated the memory of the crusades to affirm their imperial heritage; while the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have witnessed a deepening tendency within some sections of the Muslim world to equate modern political and religious struggles with holy wars witnessed nine centuries earlier.

This book explores the history of the crusades from both the Christian and Muslim perspectivesfocusing, in particular, upon the contest for control of the Holy Landand examines how medieval contemporaries experienced and remembered the crusades. It draws upon the wonderfully rich mine of available written evidence (or primary sources) from the Middle Ages: the likes of chronicles, letters and legal documents, poems and songs; recorded in languages as diverse as Latin, Old French, Arabic, Hebrew, Armenian, Syriac and Greek. Beyond these texts, the study of material remainsfrom imposing castles to delicate manuscript art and minuscule coinshas thrown new light on the crusading era. Throughout, original research has been informed by the great outpouring of modern scholarship in the field witnessed over the past fifty years.1

Containing the history of the crusades to the Holy Land between 1095 and 1291 in a single, accessible volume is a massive challenge. But it does offer enormous opportunities. The chance to trace the grand sweep of events, uncovering the visceral reality of human experiencethrough agony and exultation, horror and triumph; to chart the shifting fortunes and perceptions of Islam and Christendom. It also makes it possible to ask a series of crucial, interlocking and overarching questions about these epochal holy wars.

Issues linked to the origins and causes of the war for the Holy Land are of fundamental importance. How did two of the worlds great religions come to advocate violence in the name of God, convincing their followers that fighting for their faith would open the gates to Heaven or Paradise? And why did endless thousands of Christians and Muslims answer the call to crusade and jihad , knowing full well that they might face intense suffering and even death? It is also imperative to consider whether the First Crusade, launched at the end of the eleventh century, was an act of Christian aggression, and what perpetuated the cycle of religious violence in the Near East for the two hundred years that followed.

The outcomes and impact of these holy wars are equally significant. Was the crusading era a period of unqualified discordthe product of an inevitable clash of civilisationsor one that revealed a capacity for coexistence and constructive cross-cultural contact between Christendom and Islam? We must ask who, in the end, won the war for the Holy Land and why, but more pressing still is the question of how this age of conflict affected history, and why these ancient struggles still seem to cast a shadow over the world to this day.