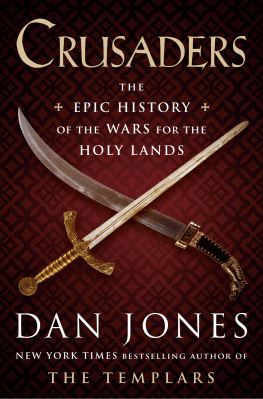

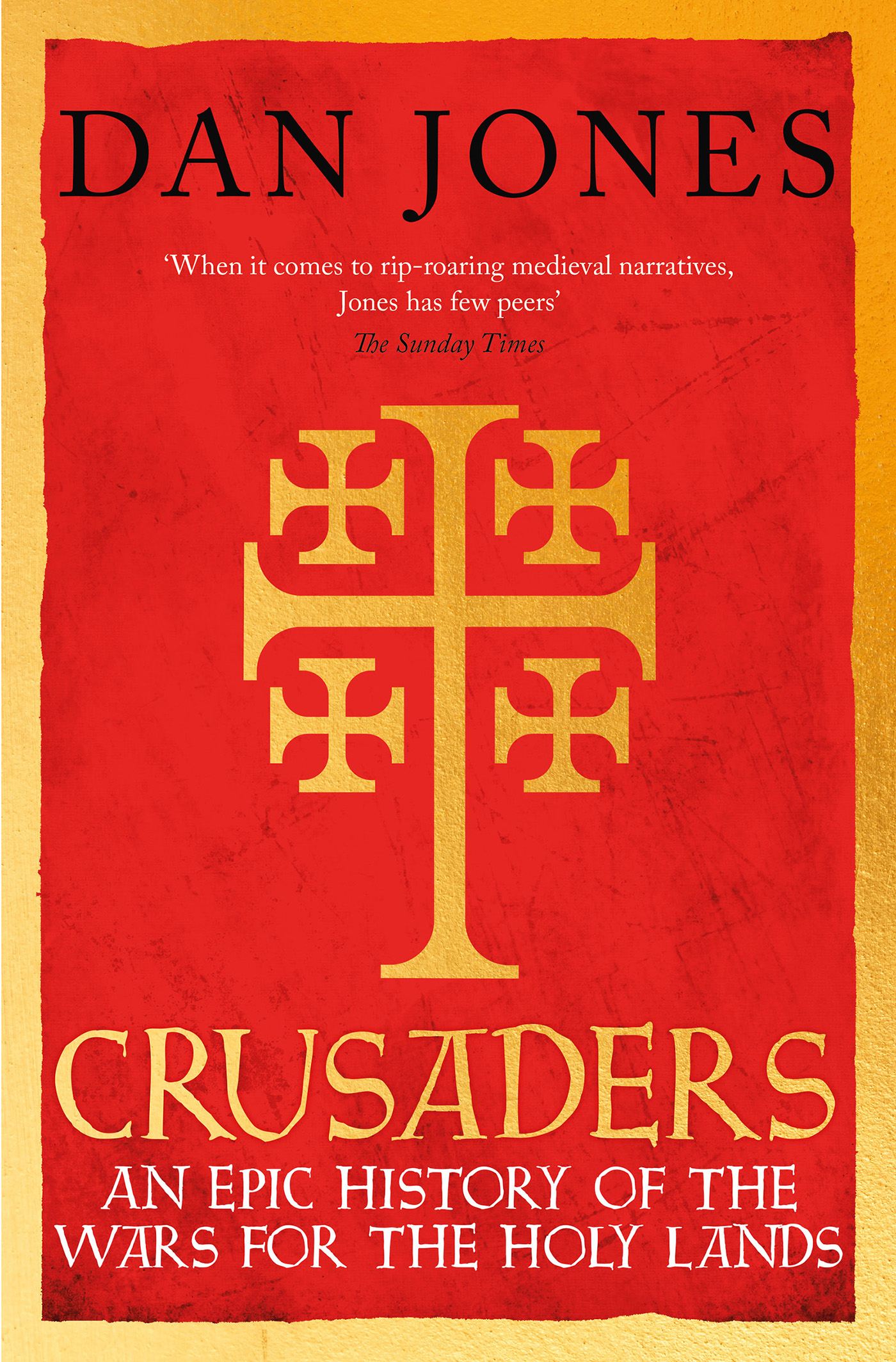

CRUSADERS

Summer of Blood: The Peasants Revolt of 1381

The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England

The Hollow Crown: The Wars of the Roses and the Rise of the Tudors

Magna Carta: The Making and Legacy of the Great Charter

Realm Divided: A Year in the Life of Plantagenet England

The Templars: The Rise and Fall of Gods Holy Warriors

The Colour of Time: A New History of the World 18501960

(with Marina Amaral)

CRUSADERS

An Epic History of the Wars

for the Holy Lands

DAN JONES

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

For Walter

First published in the UK in 2019 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright Dan Jones, 2019

The moral right of Dan Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB): 9781781858882

ISBN (E): 9781781858875

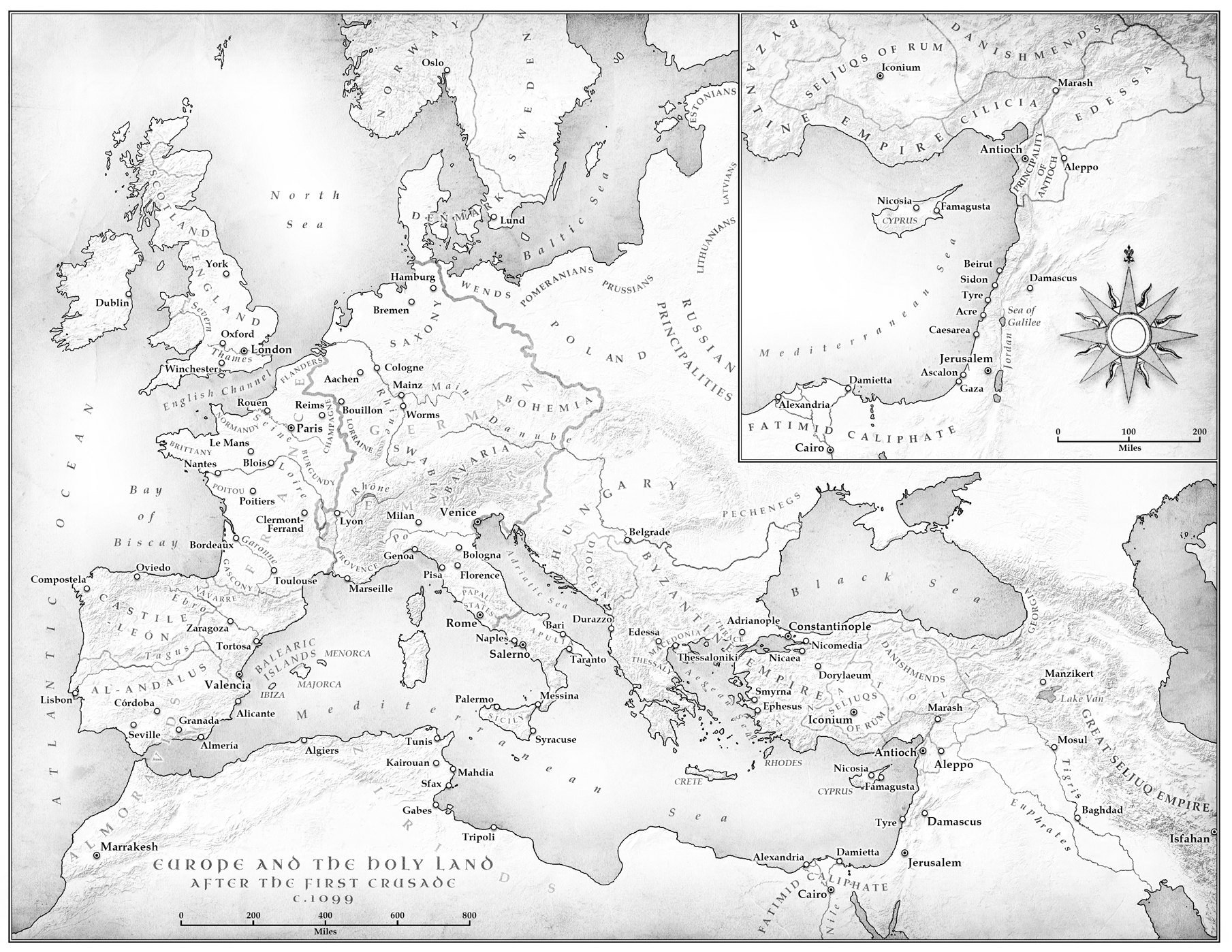

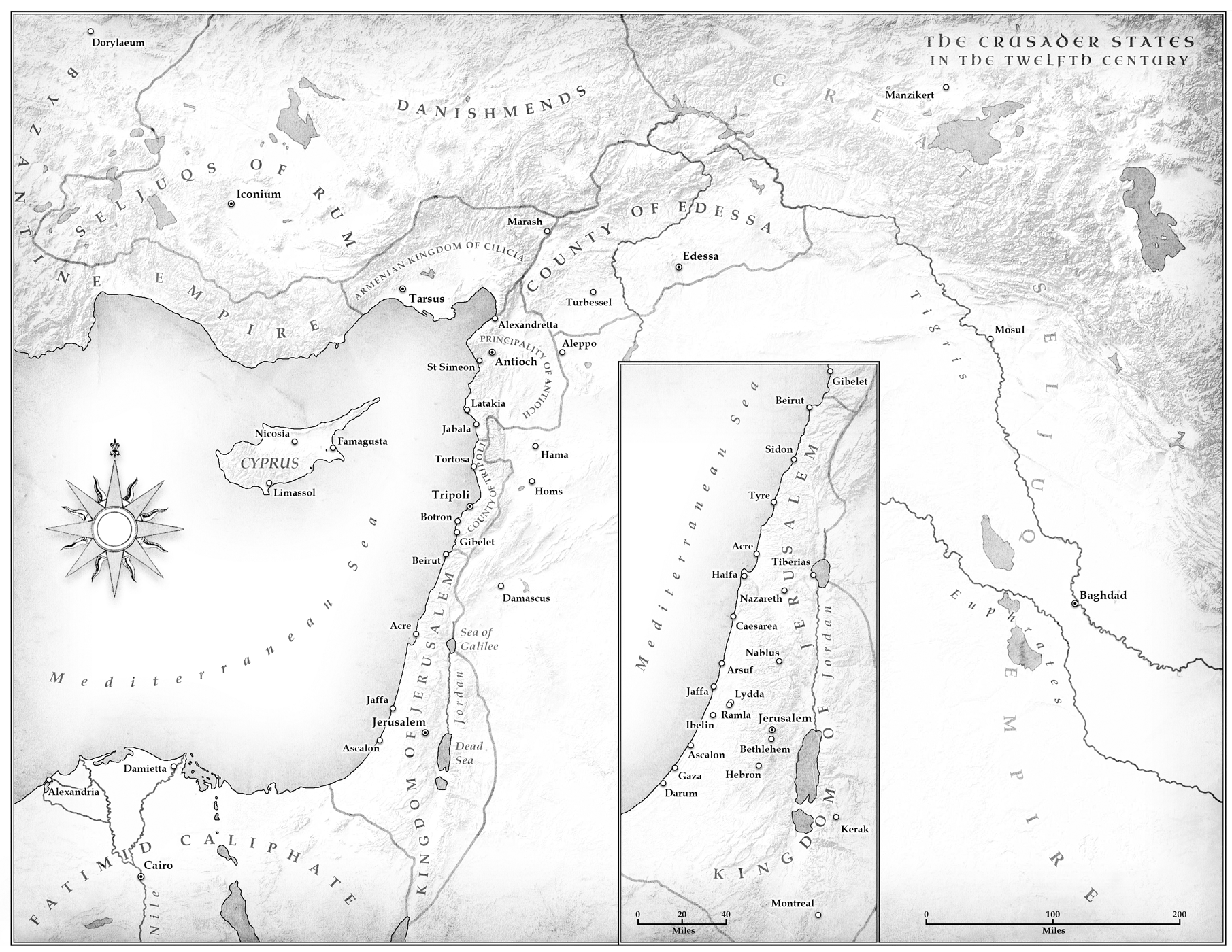

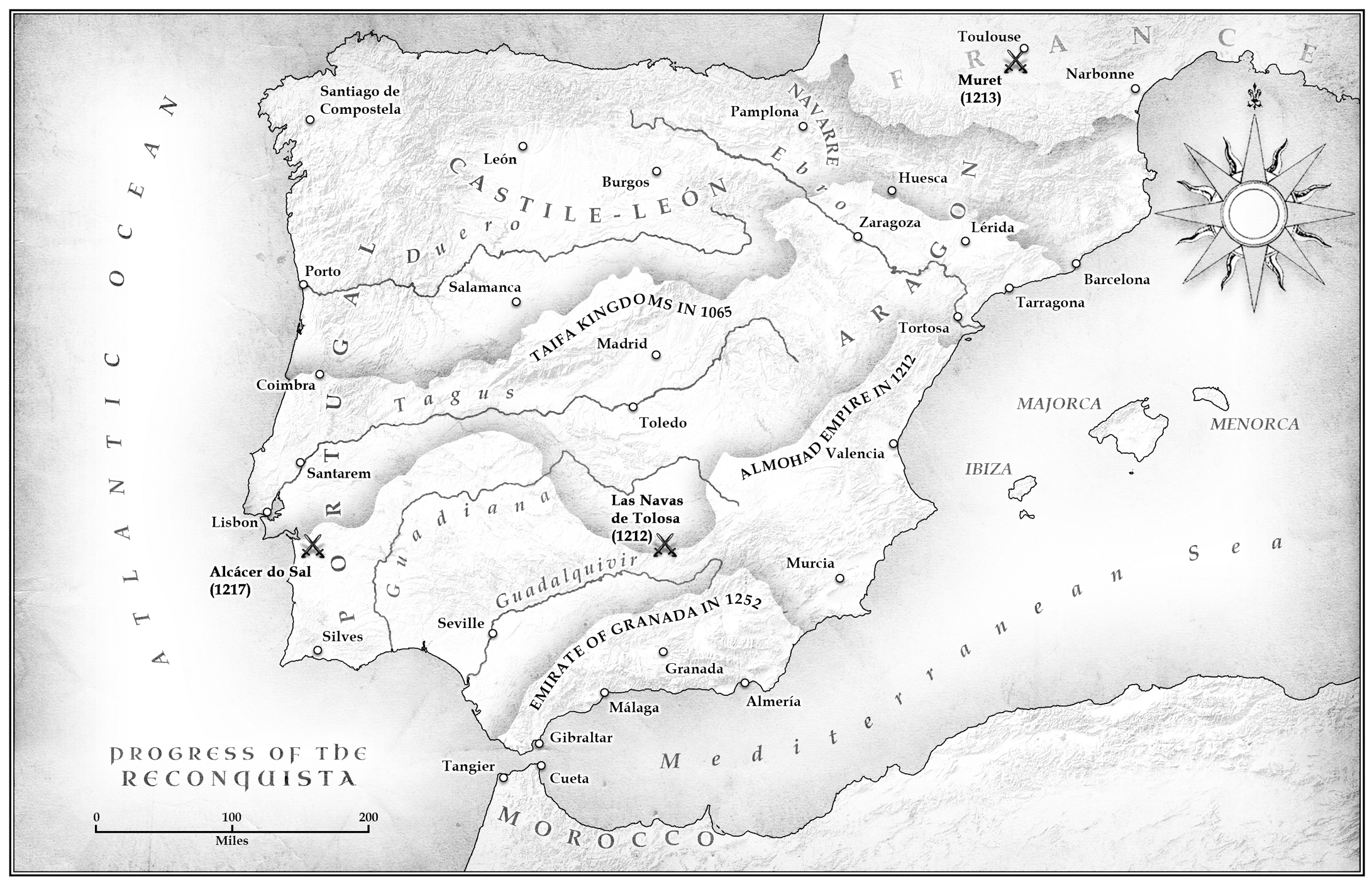

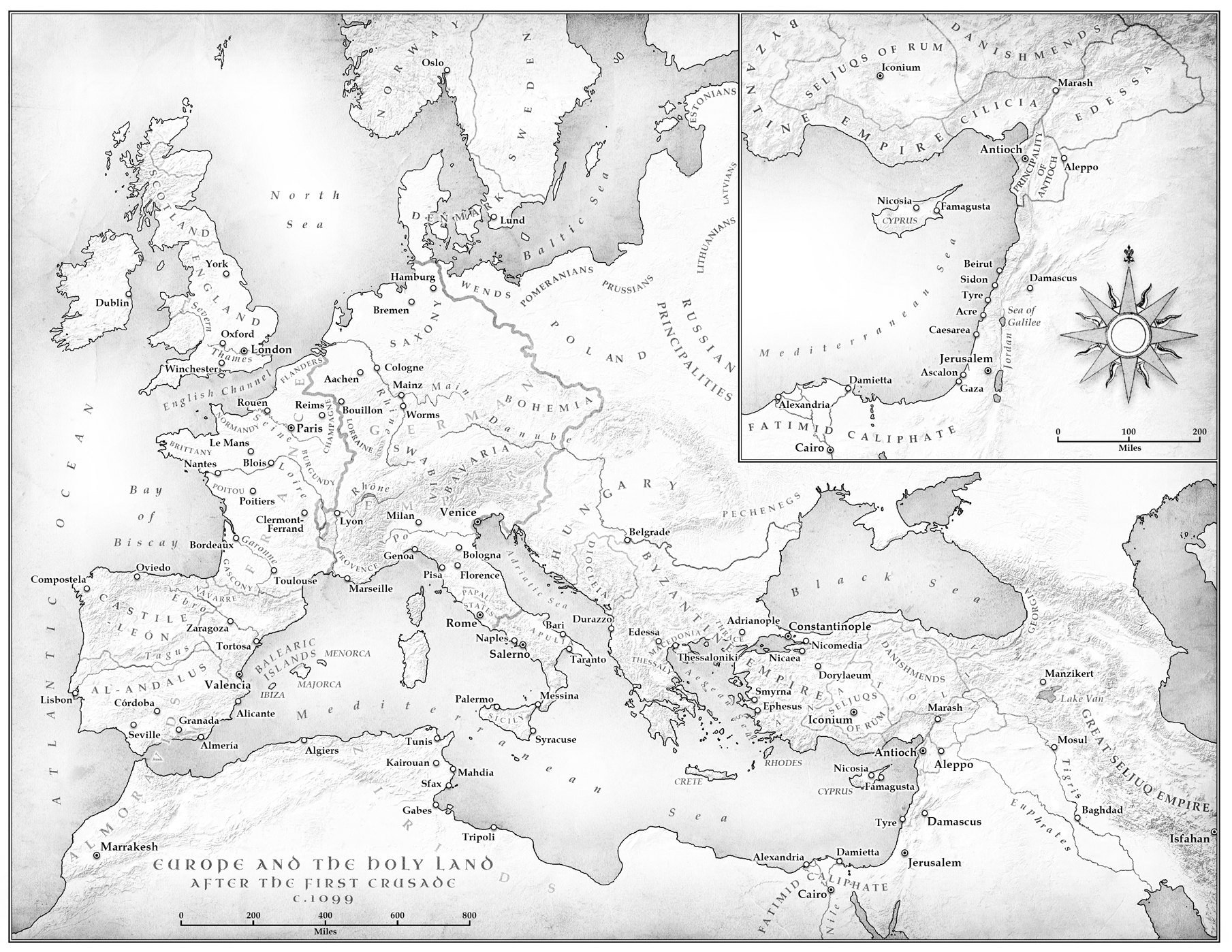

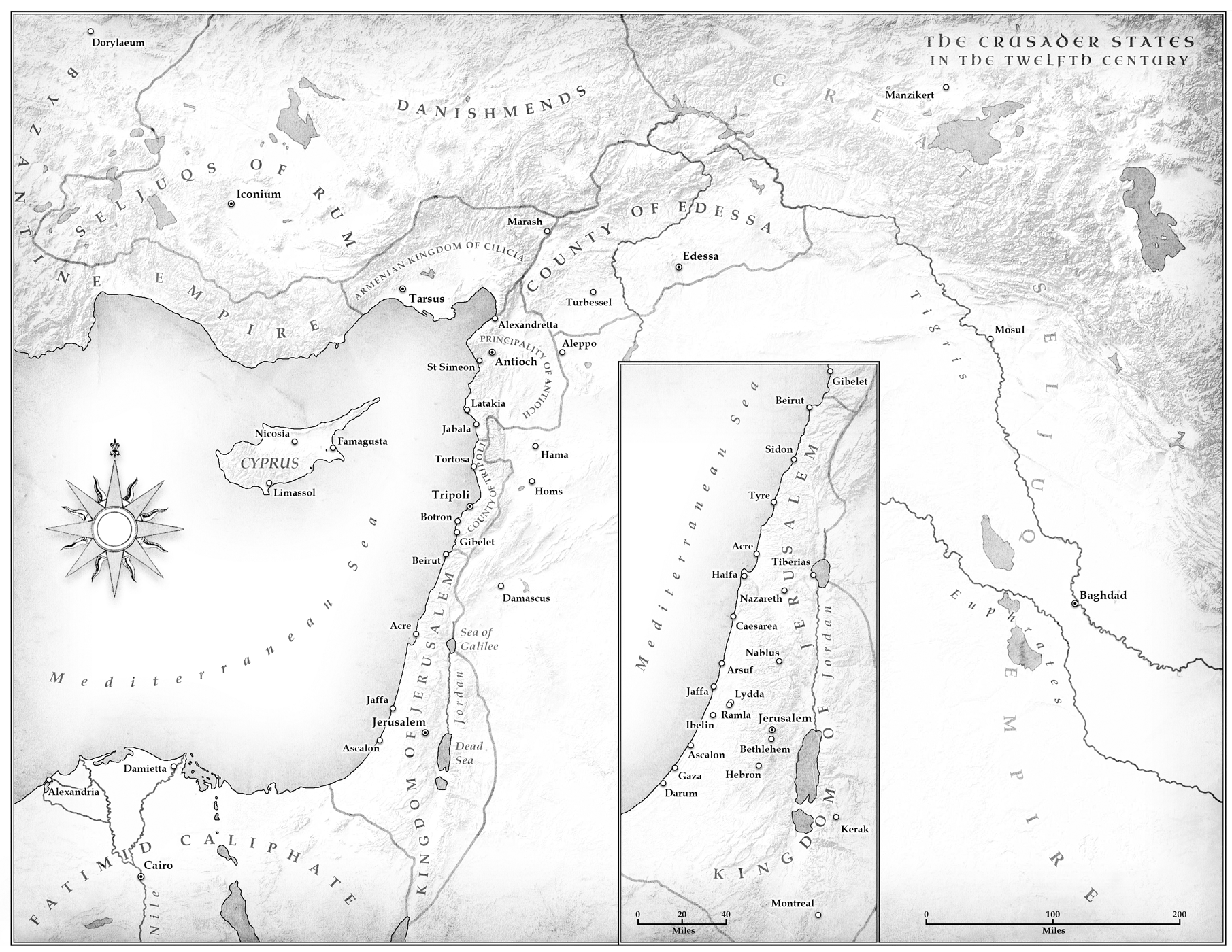

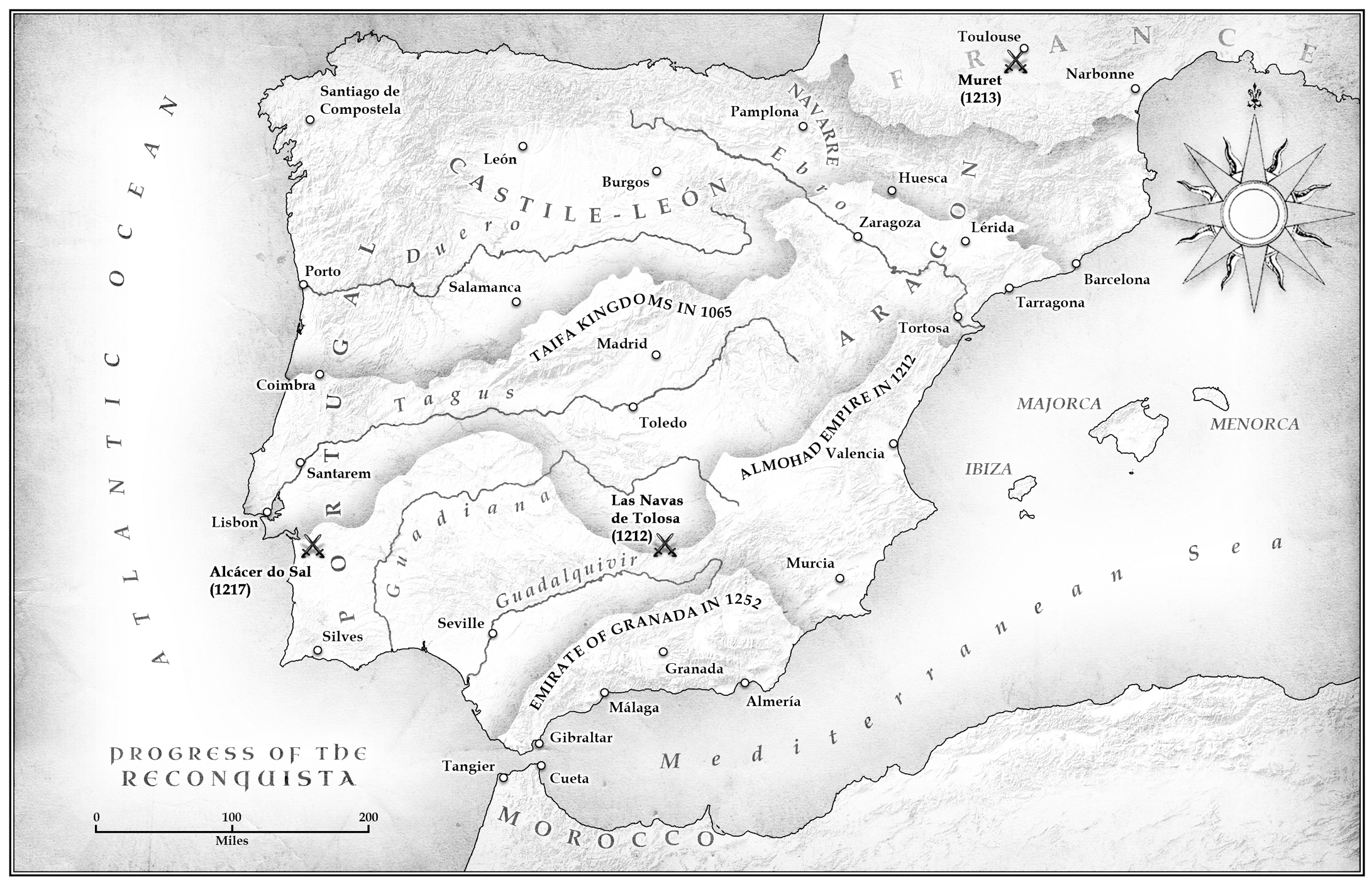

Maps by Jamie Whyte

Cover design: Estuary English

Author photo: Peter Clark

Head of Zeus Ltd

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

Contents

In those days men cared as much for furs as

they did for their immortal souls.

Adam of Bremen ( c .1076)

An epic written in blood

Shortly before Easter in the year 1188, an English archbishop of Canterbury went to Wales on a recruitment drive. Thousands of miles away, war had broken out in the eastern Mediterranean and the archbishop, whose name was Baldwin of Forde, had been tasked with recruiting several thousand able-bodied fighting men to join an army that was being deployed there.

It was, on the face of it, not an easy assignment. For those who decided to join up, the journey by land and sea to the east and back would take at least eighteen months. It would cost a lot of money. There was a high chance of shipwreck, robbery, ambush or death from disease long before the destination the Christian kingdom of Jerusalem, in Palestine was ever reached. The chances of coming home with much in the way of plunder were negligible. Indeed, the prospect of coming home at all was dauntingly slim.

The enemy commander the Kurdish sultan of Egypt and Syria, Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, colloquially called Saladin was highly capable and had already inflicted a series of devastating defeats on armies of the western Christians generically known as the Franks. The previous summer he had crushed a huge army in the field, imprisoned the king of Jerusalem, seized the holy relic of Christs cross, and evicted a Christian government from the city of Jerusalem. The only sure reward for participants in the war to take revenge on Saladin would be redeemed in the afterlife, where it was assumed that God would look favourably on participants, granting them a smoother, swifter entry into paradise.

Although in a religious age obsessed with tallying and remitting sin this was a more enticing offer than it might seem today, Baldwin nevertheless had his work cut out, as he and his entourage slogged through Wales from town to town: preaching, persuading and whipping up enthusiasm for a war against an enemy none of his audience had ever seen, in a land vanishingly few had never experienced outside their imaginations.

In a small town called Aberteifi, in west Wales, a young married couple reacted to Baldwins arrival by having a fight. The husband had decided he wanted to sign up for the crusade. His wife was adamant he was going nowhere. According to the writer Gerald of Wales, who travelled with Archbishop Baldwin and kept a vivid record of the journey (although he sadly omitted the couples names), the wife held her husband fast by his cloak and belt, and publicly prevented him from going to the archbishop. They struggled and she won. But, wrote Gerald, her victory proved horribly short lived: Three nights afterwards, she heard a terrible voice saying, You have taken my servant away from me, therefore what you must love shall be taken away from you.

That evening, lying in bed, she accidentally rolled over in her sleep and smothered to death her infant son who was sharing her bed. It was a tragedy. It was also, she realized, an omen. Although by now Archbishop Baldwin had moved on, the distraught couple went to see their diocesan bishop to report the dreadful accident and beg forgiveness.

Only one solution presented itself. They all knew what it was. Those Christians who had agreed to leave to fight Saladin advertised their status as sworn, holy warriors in the army of Christ by stitching a cross made of cloth onto the arm of their clothes.

The wife sewed on her husbands cross herself.

*

This is a book about the crusades: the wars fought by Christian-led, papal-sanctioned armies against the perceived enemies of Christ and the church of Rome during the Middle Ages. Its title, Crusaders , reflects both its theme and its approach. For a long time during the Middle Ages there was no single word to describe the crusades as we have today come to think of them: a series of eight or nine major expeditions from western Europe to the Holy Land, supplemented by a series of other, tangentially connected wars fought from the sun-baked cities of the north African coast to the frozen forests of the Baltic region. Yet from the earliest days of the phenomenon there certainly was a word for those who participated. The men and women who took part in these penitential wars in the hope of spiritual salvation were known in Latin as crucesignati those signed with the cross. In that sense, then, the idea of the crusader preceded the idea of the crusades, and that is one reason why I have preferred it here.

More importantly, however, the title Crusaders reflects the approach to storytelling that I have taken in this book. It is composed of a series of episodes featuring people who were involved in the crusades, arranged sequentially and chronologically to tell a tableau history that spans the period at large. The individuals whom I have charged with taking us on our journey are the crusaders of the books title, and they are an ensemble cast who I hope, together, can tell us the story of crusading from the front line.

In choosing these crusaders I have deliberately cast my net wide. I have selected women and men, Christians of the eastern and western churches, Sunni and Shia Muslims, Arabs, Jews, Turks, Kurds, Syrians, Egyptians, Berbers and Mongols. There are people here from England, Wales, France, Scandinavia, Germany, Italy, Sicily, Spain, Portugal, the Balkans and north Africa. There is even a band of Vikings. Some have central parts to play, others mere cameos. But this is their story.