R.F.R.

and

T.B.R.

with love

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

CHRISTIAN ROYALTY

ISABELLA I , Queen of Castile and Spain

FERDINAND V , King of Aragon, Sicily, and Spain

ENRIQUE IV THE IMPOTENT , Isabella's predecessor and half brother

ALFONSO X THE LEARNED , King of Castile (125284)

JOO II , King of Portugal

ALFONSO V , THE AFRICAN , King of Portugal (144381), Joo II's father

HENRY THE NAVIGATOR , Prince of Portugal (13941460)

CHARLES VIII , King of France (148398)

MOORISH ROYALTY

BOABDIL THE UNLUCKY , the last king of the Moorish Caliphate

MULEY ABEN HASSAN , Boabdil's father and predecessor

EL ZAGAL THE VALIANT , Boabdil's uncle

AXYA THE CHASTE , Boabdil's mother

CHRISTIAN PRELATES

TOMS DE TORQUEMADA , Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition

PEDRO GONZLEZ DE MENDOZA , Cardinal of Spain

HERNANDO TALAVERA , queen's confessor and first archbishop of Granada

ALFONSO DE OJEDA , Inquisition's firebrand

PEDRO ARBUS , inquisitor of Aragon

GIROLAMO SAVONAROLA , Dominican prior of Florence, reformer

ANTONIO DE MARCHENA , father superior of the Monastery of La Rbida

JUAN PREZ , Franciscan friar and booster of Columbus

COURT RABBIS

DON ISAAC ABRAVANEL

DON ABRAHAM SENIOR

DISCOVERERS

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS

MARTN ALONSO PINZN , captain of the Pinta

VICENTE YAEZ PINZN , captain of the Nia

DIOGO CO , Portuguese discoverer of the Congo

BARTHOLOMEW DIAS , Portuguese discoverer of Cape of Good Hope

POPES

SIXTUS IV(147184)

INNOCENT VIII(148492)

ALEXANDER VI , previously Rodrigo Borgia (14921503)

CALIXTUS III , Alexander's uncle, first Borgia pope (145558)

OTHERS

CIDI YAHYE , emir of Almera, defender of Baza, apostate

RODRIGO PONCE DE LEN , marquis of Cdiz

LUIS DE SANTNGEL , treasurer of Aragon

MUSA BEN ABIL , Moorish general, last holdout of the Alhambra

COUNT OF MEDINA CELI , advocate of Columbus

IIGO LPEZ DE MENDOZA , count of Tendilla

PROLOGUE

GRANADA, SPAIN

From my terrace in the ancient Arabic barrio of Albaicn, I look across the Darro River to the great red palace of the Alhambra and then down the narrow gorge to the rotund Gothic Royal Chapel, shaped to suggest a crown, where King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella are buried. On the side of the chapel these days a banner hangs to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Queen Isabella's death, and there is talk again of her beatification as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church.

From my terrace in the ancient Arabic barrio of Albaicn, I look across the Darro River to the great red palace of the Alhambra and then down the narrow gorge to the rotund Gothic Royal Chapel, shaped to suggest a crown, where King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella are buried. On the side of the chapel these days a banner hangs to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Queen Isabella's death, and there is talk again of her beatification as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church.

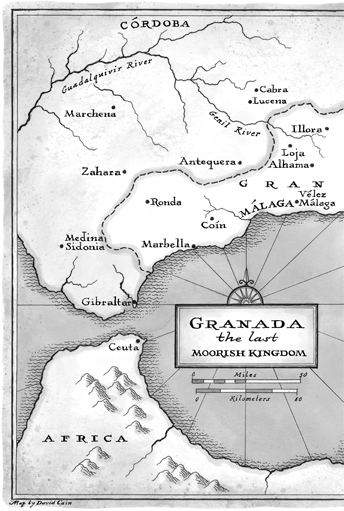

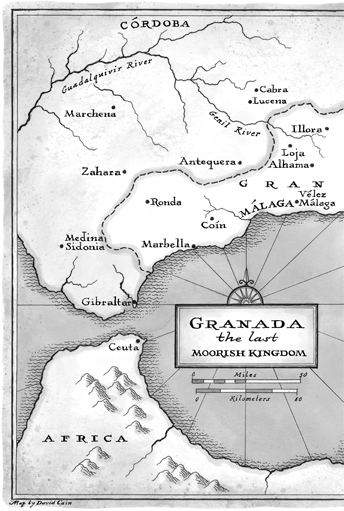

No banners hang on the Alhambra to commemorate the final defeat in 1492 of the glorious, lost culture that was the Caliphate of the Moors. There are, however, other reminders. The memory of the gruesome train bombings in Madrid this year is still fresh and raw. Just as the perpetrators of the crimes of September 11 invoked the Christian Crusades of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Islamic perpetrators of the Madrid atrocity sought to justify their mass murder partly by invoking the defeat of the ancient Moors. The crime was supposed to be a long-overdue act of historical revenge for the attack on Muslims in Al Andalus (as the Moorish Caliphate was known).

You know the Spanish crusade against Muslims and the expulsions from Al Andalus are not so long ago, the Al Qaeda spokesman said, in taking responsibility.

Far-fetched, hollow, and sinister as this rationale sounds to Westerners, it is important to appreciate that historical resentments are deeply and sincerely felt in the Islamic world. The conflict between the Catholic monarchs of fifteenth-century Spain and the Moorish caliphs of Granada was a holy war between Christianity and Islam. Its ferocity and passion were no less than that of the Crusades or, for that matter, of the conflict that has been allowed to develop in the Middle East today between the West and the Arab world, between Christianity and Islam. Undeniably, in the fertile imagination of some Arab activists, the recapture of Al Andalus for Islam is coupled with the termination of the state of Israel and the end of the American occupation of Iraq. Given the splendor of Moorish culture, this fantasy can have broad emotional appeal.

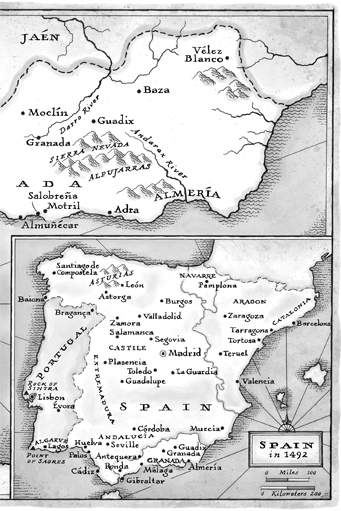

The Alhambra and the Royal Chapel are the physical monuments to the epic events that happened here in the extraordinary, seminal year of 1492. In the Tower of the Comares across the way, in the exquisite, ethereal Hall of the Ambassadors, it is said that Columbus received his final instructions for his adventure across the Ocean Sea. No artistic bricks or statuary exist to praise or mourn the two-hundred Jewish families who lived in Granada and who were expelled from Spain a few months before Columbus received his royal authority. But when Columbus made his way from Granada to Seville and then on to Palos, from whence he departed for the New World, the roads must have been clogged with Jews departing Spain, scattering across sea and border in response to the Edict of Expulsion of Ferdinand and Isabella and their Inquisition. Columbus sailed on the day after the date set by the Inquisition as the final deadline for the departure from Spanish soil of all Spanish Jews, the fabled Sephardim. The betrayal and suffering of Sephardic Jews comes down to us today as both catastrophe and prologue.

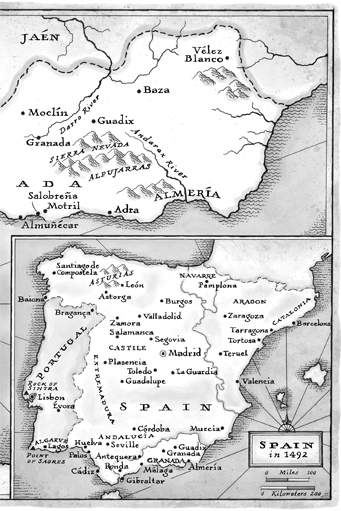

In fact, it is little appreciated, especially by Americans, how intimately the discovery of the New World is bound up with the victory of Christianity over Islam in the so-called Spanish Reconquest, with the expulsion of Spanish Jews, with the terrible Spanish Inquisition, and with the papacy of a Borgia pope. In this book I have tried to make those links. It is one of the enduring ironies of this period that the barbaric, medieval institution of the Spanish Inquisition contributed greatly to the founding of the first modern nation-state.

The inclination to ignore or downplay these connections continues today. In the years before the millennium of 2000, the Vatican promised to purify its history by looking into the dark corners of its past, such as the inquisitional trial and imprisonment of Galileo in the seventeenth century. Despite this, in June 2004, the Holy See announced that the Spanish Inquisition was really not as bad as it has been portrayed. Fewer witches were burned at the stake, its pronouncement read, and fewer heretics were tortured into conversion than had been previously thought. Vatican Downsizes the Inquisition was the headline in the New York Times. Purifying in 1998 turned to sanitizing in 2004.

It has been suggested that the three most important years in American history are 1492, 1776, and 1865. Of these, 1492 goes far beyond American history. It is pivotal as well in Spanish history, in Jewish and Arab history, in World and Church history. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine another single year in the past millennium when so many significant strands of history came together and so changed the world in one swoop: the completion of the 500-year movement to conquer the Moors, the end of the 800-year reign of the glorious culture of Islamic Spain, the consolidation of the modern Spanish state, the sinister explosion of the Spanish Inquisition, the Spanish renaissance in art and literature, the expulsion of the Jews, the discovery of the New World, and the subsequent division of the world between Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence.

From my terrace in the ancient Arabic barrio of Albaicn, I look across the Darro River to the great red palace of the Alhambra and then down the narrow gorge to the rotund Gothic Royal Chapel, shaped to suggest a crown, where King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella are buried. On the side of the chapel these days a banner hangs to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Queen Isabella's death, and there is talk again of her beatification as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church.

From my terrace in the ancient Arabic barrio of Albaicn, I look across the Darro River to the great red palace of the Alhambra and then down the narrow gorge to the rotund Gothic Royal Chapel, shaped to suggest a crown, where King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella are buried. On the side of the chapel these days a banner hangs to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Queen Isabella's death, and there is talk again of her beatification as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church.