Black from Tula and Black Krim tomato seedlings.

Black from Tula and Black Krim tomato seedlings.

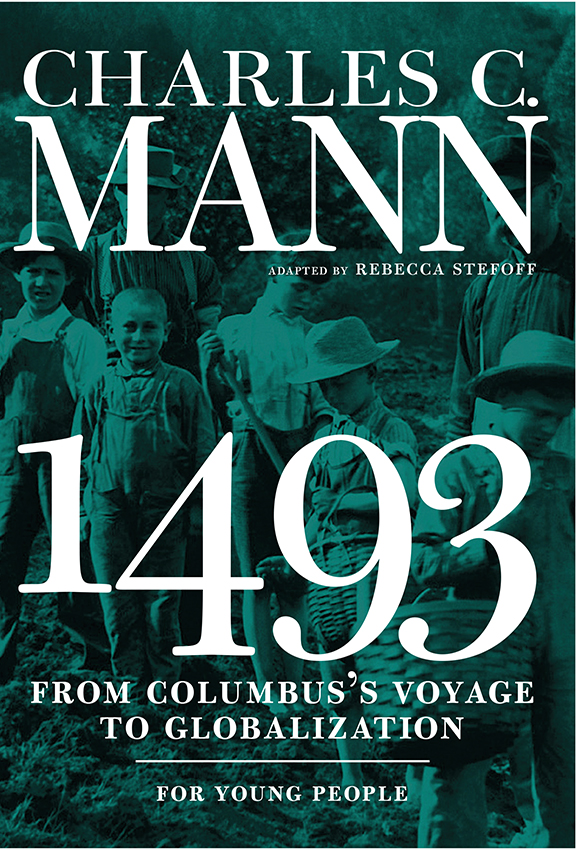

A TRIANGLE SQUARE BOOK FOR YOUNG READERS

PUBLISHED BY SEVEN STORIES PRESS

Copyright 2014 by Charles C. Mann

For permissions information see page 405.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise, without the

prior written permission of the publisher

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors may order free examination copies

of Seven Stories Press titles.

To order, visit www.sevenstories.com/textbook

or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Book design by Pollen/Stewart Cauley/Abigail Miller, New York

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data,

Mann, Charles C.,

1493 for young people : from Columbuss voyage to globalization

Charles Mann; adapted by Rebecca Stefoff.

pages cm.

(For young people series)

ISBN 978-1-60980-630-9 (hardback)

ISBN 978-1-60980-663-7 (paperback)

1. History, ModernJuvenile literature.

2. Economic historyJuvenile literature.

3. CommerceHistoryJuvenile literature.

4. AgricultureHistoryJuvenile literature.

5. EcologyHistoryJuvenile literature.

6. Industrial revolutionJuvenile literature.

7. Slave tradeHistoryJuvenile literature.

8. AmericaDiscovery and exploration

Economic aspectsJuvenile literature.

9. AmericaDiscovery and exploration

Environmental aspectsJuvenile literature.

10. Columbus, ChristopherInfluenceJuvenile literature.

11. GlobalizationJuvenile literature.

I. Stefoff, Rebecca, 1951-II. Title.

III. Title: Fourteen ninety-three for young people.

IV. Title: Fourteen hundred ninety-three for young people.

D228.M35 2015

909.08dc23

2014047241

Printed in China

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

ABOUT THIS BOOK

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT THE WHOLE WORLD, BUT IT began in a single garden.

More than twenty years ago I saw a news article about local college students who had grown a hundred different kinds of tomato. Visitors were welcome to take a look at their work. Because I like tomatoes, I decided to drop by with my eight-year-old son. When we arrived at the college greenhouse I was amazed. Id never seen tomatoes in so many different sizes, shapes, and colors.

A student offered us samples. One alarmingly lumpy tomato was the color of an old brick, with a broad greenish-black patch around the stem. Its taste was so intense that it jolted my mouth awake. Its name, the student said, was Black from Tula. It was an heirloom tomato, an old variety. It had been developed in the nineteenth century in Ukraine, south of Russia.

I thought tomatoes came from Mexico, I said. What are they doing breeding them in Ukraine?

The student gave me a catalog of heirloom seeds for tomatoes, chile peppers, and beans (the kind of beans in chili, not green ones). All three crops originated in the Americas, but the catalog showed many varieties that came from overseas: Japanese tomatoes, Italian peppers, beans from the Congo. Wanting more of those strange but tasty tomatoes, I ordered some seeds, sprouted them in plastic containers, and stuck the seedlings in a garden, something Id never done before.

My question to the student had been off the mark, as I discovered when I did some research. Tomatoes probably originated not in Mexico, but in the Andes Mountains of South America. Wild tomato species that still grow there are small, and only one is (barely) edible. The real mystery is not how tomatoes ended up in Ukraine or Japan but how the ancestors of todays tomato journeyed from South America to Mexico, where plant breeders made the fruits bigger, redder, and (most importantly) more edible. Why carry useless wild tomatoes for thousands of miles? Why hadnt South Americans learned to use the tomato? How had people in Mexico gone about changing the plant to meet their needs?

These questions touched on a long-standing interest of mine: the original inhabitants of the Americas. As a reporter for the journal Science, I had spoken with researchers about new findings on the size and advanced development of longago native societies in the Americas. Eventually I wrote 1491, a book about the history of the Americas before Christopher Columbuss arrival in 1492. The tomatoes in my garden carried a little of that history in their DNA.

After Columbus

My tomatoes also carried some of the history after Columbus. Beginning in the sixteenth century, Europeans took tomatoes around the world. After convincing themselves that the strange red blobs were not poisonous, farmers planted them from Africa to Asia. In a small way, the plant had a cultural impact everywhere it was sown. Sometimes the impact was not so smallits almost impossible to imagine southern Italy without tomato sauce.

Still, I didnt grasp that transplants such as tomatoes might have played a role beyond the dinner plate until I came across a paperback titled Ecological Imperialism, by a geographer and historian named Alfred Crosby. Wondering what the title could refer to, I picked up the book. The first sentence seemed to jump off the page: European emigrants and their descendants are all over the place, which requires explanation.

Heirloom tomatoes, including Black from Tula at the top left and bottom right.

Exactly. Most Africans live in Africa, most Asians in Asia, and most Native Americans in the Americas. People of European descent, though, are thick on the ground in distant realms such as Australia, the Americas, and southern Africa. They are successful transplants. But why? It is as much a puzzle as tomatoes in the Ukraine.

Historians used to explain Europes spread across the globe in terms of European superiority. They argued that Europeans had simply had better social systems, science, ships, or weaponry than the cultures whose lands they conquered and colonized. Yet Crosby argued that, in the long run, Europes most important advantage was biological. European ships that sailed from continent to continent carried not just people but plants and animals as wellsometimes on purpose, sometimes accidentally. After Columbus, ecosystems that had been separate for ages suddenly met and mixed in a process Crosby called the Columbian Exchange. The exchange took corn (maize) to Africa, sweet potatoes to East Asia, horses and apples to the Americas, and rhubarb and eucalyptus to Europe. It also swapped around many insects, grasses, bacteria, and viruses.