THE GREAT LIVES SERIES

Great Lives biographies shed an exciting new light on the many dynamic men and women whose actions, visions, and dedication to an ideal have influenced the course of history. Their ambitions, dreams, successes and failures, the controversies they faced and the obstacles they overcame are the true stories behind these distinguished world leaders, explorers, and great Americans.

Other biographies in the Great Lives Series

MIKHAIL GORBACHEV:The Soviet Innovator

JOHN F. KENNEDY:Courage in Crisis

ABRAHAM LINCOLN:The Freedom President

SALLY RIDE:Shooting for the Stars

HARRIET TUBMAN:Call to Freedom

For middle school readers

A Fawcett Columbine Book

Published by Ballantine Books

Copyright 1989 by the Jeffrey Weiss Group, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 89-90817

eISBN: 978-0-307-80087-9

v3.1

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A special thanks to educators Dr. Frank Moretti, Ph.D., Associate Headmaster of the Dalton School in New York City; Dr. Paul Mattingly, Ph.D., Professor of History at New York University; and Barbara Smith, M. S., Assistant Superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District, for their contributions to the Great Lives Series.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1

The Captain General Takes Charge

Chapter 2

In Love with the Sea

Chapter 3

Pleading His Case

Chapter 4

Convincing the Confessor

Chapter 5

Finding a New World

Chapter 6

An Incomparable Land

Chapter 7

Colonizing the New World

Chapter 8

The Last Voyage

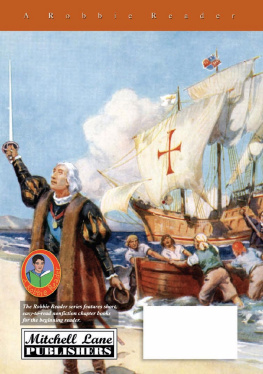

Christopher Columbus in his cabin aboard the caravel Santa Mara, hearing his men shouting, Land! Land! Columbus thought he had discovered the long-sought western route to Asia, but in fact he had reached lands then unknown to Europeansthe Americas.

1

The Captain General

Takes Charge

O NCE AGAIN THE night was mild, the sea was calm, and the giant sailing vessel, the Santa Mara, raced along. Her captain, Christopher Columbus, was well-pleased with her progress. Since leaving the Canary Islands, an archipelago located off the northwest coast of Africa, the Santa Mara and her sister ships, the Nia and the Pinta, had made remarkable time. Over the past five days, as Columbus had just finished noting in his ships log, the Santa Mara had maintained an average speed of eight knots. Other ship captains considered five knots in such latitudes to be adequate speed.

Columbus shut the log and placed it in the heavy chest that sailors used to store their belongings while at sea. He looked at his quarters. A similar log, an apparent duplicate of the one he had just finished writing in, lay on top of the crude wooden table that served as his desk. It shared the tabletop with a leather-bound Bible. A crimson ribbon held the Bible open to a page in the Old Testaments Book of Isaiah, where Columbus had underscored a particular passage: The isle saw it, and feared; the ends of the earth were afraid, drew near, and came. In an age characterized by intense religious devotion, the depths of Columbuss faith made him special. The Biblical passage, like others that he had singled out, provided the captain with solace on his long journey and served as the justification for the extraordinary adventure he was embarked upon.

Next to the Bible was a well-thumbed copy of Imago Mundi, a geographical and theological treatise by the French writer Pierre dAilly. Columbus read Imago Mundi most nights, and his confidence was bolstered by the learned Frenchmans claim that Asia could be reached in a few days by sailing west from Africa. The weighty volume rested atop nautical charts, on which Columbus charted his own progress and consulted the reckonings of other mariners.

Columbus snuffed out the candle that lit his small cabin and stepped forth onto the deck. High above the Santa Maras three masts a thin line of clouds drifted across the face of the full moon. The drifting clouds gave the illusion that the moon, too, was speeding toward the west. Columbus considered it a good omen, one more sign that the heavens themselves favored this journey. Thousands of stars twinkled in the sky. There were more stars by far than could be seen from even the highest rooftop in Genoa, Italy, or Lisbon, Spain, the cities where Columbus had spent most of his days when not at sea. There were more stars, too, than hed seen on any of his earlier voyages. They stretched all the way to the horizons at all four points of the compass. It was as if, Columbus thought, in journeying to uncharted regions of the earth, hed been allowed a glimpse of heaven. The star-filled skies might have filled another man with a sense of his own insignificance and of the precariousness of his situation. The Santa Mara and her sister vessels were now nearly one months sailing time beyond the nearest known land. No one knew how many days of sailing there would be before the ships reached land. The three small ships, manned by only ninety sailors, lay adrift on the vast and powerful ocean. But Columbus was reassured by the numberless stars above him, and by the broad and restless expanse of sea that surrounded him. It was not mere bravery that gave him the assurance to continue, but faith. Columbus believed that the awe-inspiring beauty that surrounded him could only be the handiwork of the one true God, and he felt secure in his Lord and Saviors protection. If only my crewmen shared my belief, Columbus thought. They were devout, of course, and like most Spanish they were good Catholics, faithful in their recitation of their morning prayers. However, they were also superstitious, poorly educated, and fearful.

On board ship, on this night, Columbuss senses exulted. He delighted in the sting and tang of the salt spray. The creaking of the riggings rang like chimes to his ears. The full-breasted swell of the sails thrilled him more than any great work of art. Even the hardships of shipboard life the uncomfortable quarters, the unsanitary conditions, the salty water, the monotonous diet of salt-preserved meat, dried peas, and the hard wheat biscuit known as hardtack did not bother him. Again, it was his faith that gave him the strength to endure such discomforts. As his body grew lean and his skin coarsened from the limited diet, and as his white hair grew long and unruly, he thought of the many saints and martyrs who had suffered for their religious beliefs. Next to their suffering, his own trials seemed unimportant.