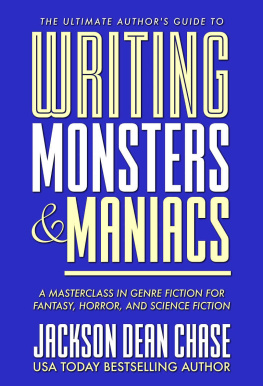

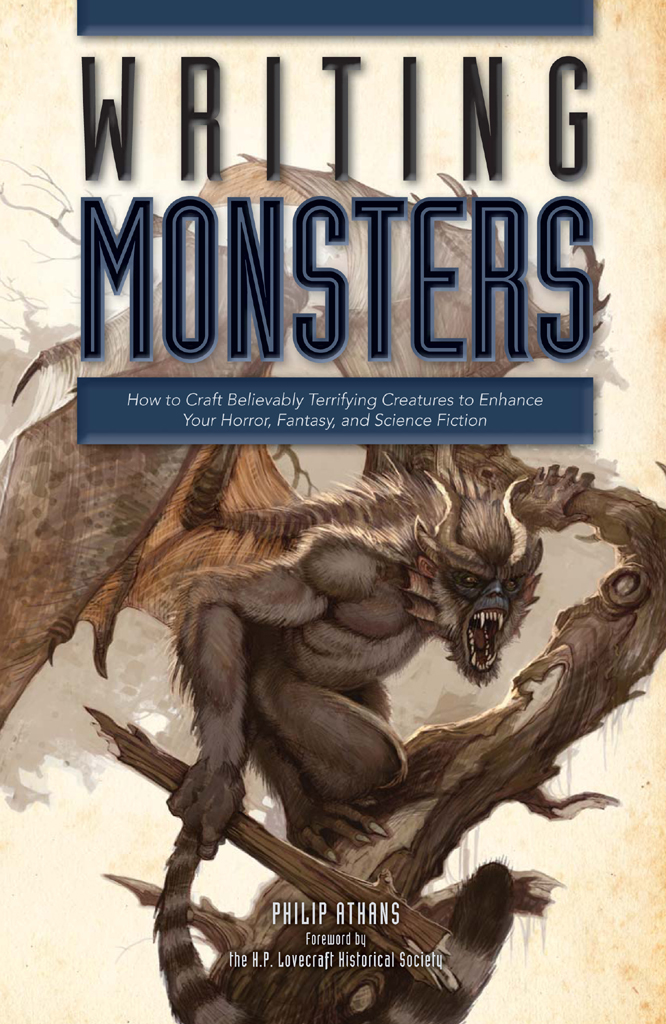

WRITING

MONSTERS

How to Craft Believably Terrifying Creatures to Enhance Your Horror, Fantasy, and Science Fiction

PHILIP ATHANS

Foreword by

the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

DEDICATION

This book is for George, who hasnt had a book dedicated to him yet. Why not one about monsters?

O, CREATOR! CAN MONSTERS EXIST IN THE SIGHT OF HIM WHO ALONE KNOWS HOW THEY WERE INVENTED, HOW THEY INVENTED THEMSELVES, AND HOW THEY MIGHT NOT HAVE INVENTED THEMSELVES?

CHARLES BAUDELAIRE

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Its a genuine pleasure to read Philip Athanss excellent book Writing Monsters. Monsters are just members of the family at the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society, and sometimes we take them for granted. Around here we have Deep Ones singing solstice carols, and shoggoth is a job title. But Mr. Athans reminds us of the tremendous power of monsters, their limitless variety, their multivarious forms, their ability to terrify, to fascinate, to entertain, and to provoke reflection.

While Mr. Athans draws from an extremely impressive array of monstrous sources, we are, of course, particularly delighted to see the works of H.P. Lovecraft cited so frequently and so appropriately in this discussion. Lovecraft was indeed, as Athans states, a master of the monster.

In Lovecrafts world, monsters are quite simply all around us all the time, and humans who read too much or look too hard learn this to their regret. He has monsters in every imaginable place: beneath the earth, under the sea, among the stars, on your doorstep, and writhing insanely at the very center of the cosmos. There are alien races from other realms and times, god-like cosmic entities of unfathomable power, teratological hybrids borne of miscegenation, and unspeakable creatures stitched together by mad science, summoned by black magick, or revealed by fantastic technology. He even has monsters that make other monsters, such as the Elder Things and their uncontrollable creations, the shoggoths. Indeed, in Lovecrafts world all earthly life, including the human race itself, is the resultby joke or mistakeof the monster-making process.

There can be no doubt that Lovecraft identified with his monsters. In fact, he had virtually no interest at all in ordinary people. A difficult childhood, chronic ill health, and a precociously sensitive nature left him feeling alienated from himself and his fellow man. One of his early signature tales, The Outsider, ends when the first-person narrator sees himself in a mirror for the first time and realizes that he himself is a horrifying monster. In The Shadow Out of Time, the protagonist suffers a monstrous invasion of his consciousness by the Great Race of Yithparalleling a multiyear nervous breakdown that Lovecraft suffered in his teenage years.

Lovecraft seemed to have the keenest appreciation for creatures that were not hemmed in by the constraints of time and space he felt in his own life. The Mi-Go traveled interstellar space and collected representative mindsthe best and brightestof the species they encountered. The Great Race could collectively change their physical forms and travel through time to capture information from every age. And even the bizarre Elder Things embodied traits Lovecraft valued most highly. Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star spawnwhatever they had been, they were men! Lovecrafts monsters were reflections of himself, strange in form, boundless in intellect, but able to exceed mere humanity through a mastery of the vastness of space and the ruthlessness of time.

But if Lovecraft sometimes thought of himself as a monster, the many friends and colleagues that he helped and encouraged surely saw him in a more favorable light. We sometimes forget that Lovecraft wrote more letters than pieces of fiction, many filled with thoughtful advice and support for other writers who were often younger and less experienced. Mr. Athanss book is in much the same spirit and will be of value to writers of all kinds, whether of prose fiction, scripted drama, games, or something else. May this thorough contemplation of monsters and its many well-chosen examples help to fire your imagination and in turn the imaginations of your audience.

Write your monsters well, but let them keep some secrets, too. Where some monsters like Godzilla and Dracula and zombies have taken center stage and permeated popular culture, Lovecrafts monsters have remained elusive, marginal, subliminal, and alien. Although we might occasionally wish that Lovecraft would receive the popular adulation we feel he deserves for his fundamental contributions to monsterdom, we cannot regret that even his most famous creationsCthulhu, Yog Sothoth, the Colour Out of Space, and their fellowshave remained in the shadows at the edges of humanitys consciousness. Thats where Lovecraft meant them to be, because thats where theyre the most frightening and effective. Part of what makes any monster scary is that it is unknown and incomprehensible: It is weakened when it steps fully into the light.

Ludo Fore Putavimus,

Andrew Leman and Sean Branney

The H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

www.cthulhulives.org

INTRODUCTION

REALISM VS. PLAUSIBILITY

That was unrealistic!

Weve all heard this standard complaint from friends, critics, even ourselves after reading a particularly forgettable book, seeing a D-list monster movie, or watching a badly produced TV show.

Its a common criticism. But do we really expect realism from the fantasy, science fiction, or horror genres? Arent these books, movies, and TV shows inherently unrealistic? Lets face it: As soon as a dragon swoops in, a starship engages its faster-than-light engines, or somebody turns into a werewolf, realism has gone right out the window.

Yet that single complaint persists. Those flying monkeys were unrealistic. That alien cyborg was unrealistic. Those vampires were unrealistic.

Admittedly this might be an exercise in semantics, but consider this: Do we find those things unrealistic, or do we find them implausible? A fine line separates the two, but for a genre author (in any media) its an essential question.

Realistic implies that this thing, whatever it is, is true to its actual, definable, measurable, observable nature. A realistic description of a dog, for instance, would list only what we know about dogs, describing in detail a dogs behavior, appearance, and so on.

But its impossible to list only what we know about a dragon, since there is nothing to know, factually, about a creature that doesnt exist. Instead, we have to try to make this imaginary beast seem real. Your readers know your description does not come via direct observation, like the description of a dog would, but you still need to make a case for that dragon within the context of your storys imagined world. You need your readers to accept what you give them, to have them say, Okay, Ill buy that.

Readers and viewers of fantasy, science fiction, and horror want to leave the real world behind and explore a bit of the impossible. Very rarely is the fantastic nature of these genres hidden. The cover art, movie poster, or game box makes it plain that you are about to enter a strange fantasy world or a bizarre futurescape. Genre fans like unrealistic. We understand that theres no such thing as a dragon, but we want authors to produce a plausible facsimile of one.