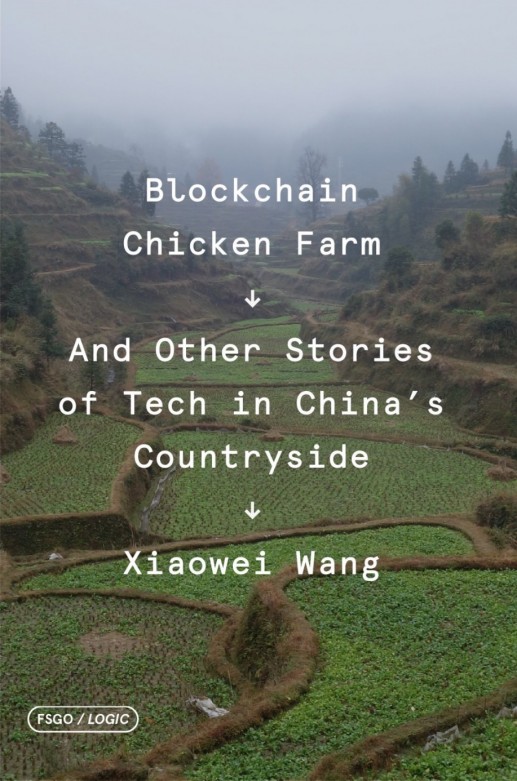

Xiaowei Wang - Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside

Here you can read online Xiaowei Wang - Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside

- Author:

- Publisher:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

The pace of writing a book is slower than the pace of world events. This is a book about technology in China, where change happens particularly fast. Unsurprisingly, many tech companies have been complicit in state violence, persecution, and systemic racism, as well as the silencing of dissent in many regionsincluding Xinjiang, home to the indigenous Uyghur people. The inclusion of such companies in this book is far from an endorsement. I oppose and condemn all forms of state violence, and I encourage readers to critically engage with the work of scholars and journalists in order to understand the role that tech companies play in maintaining racial capitalism worldwide.

This evening, I am brushing my teeth surrounded by dozens of pin-size black worms that roil and roll along white ceramic tile. A childs socks and underwear are hung out to dry on a small rack next to the sink. Its been raining all day. Im in a small village in southern China, at the border of Jiangxi and Guangdong. I arrived in the village to try to understand how e-commerce has affected life here, with farmers selling goods directly to consumers, using WeChats robust mobile payment system. After missing the last bus back to the nearest city, I am now on an involuntary meditation retreat.

Since Im American, my hosts have assumed I need spacious, extraordinarily comfortable conditions, which is why Im staying at the most modern house in the village, by myself. Its a two-story concrete building with an outhouse that has a ceramic squat toilet, just a few convenient steps away from the front door.

Its so cold here that I can see my breath inside. There are no radiators, just a small plastic space heater that defeatedly wheezes lukewarm air. Its the only sound I hear besides a low, watery gurgle, accompanied by the wind rattling through cracks of the window frame.

Nighttime is dense and dark here, with no streetlights and few houses, eerily emphasized by the silence of the village. My movements feel muffled and dull. I am unused to this kind of solitude, as someone who spends most of my time in cities, and I am scaredstuck in a new place with only the worms to talk to, maybe a ghost or two, replaying supernatural horror movies in my mind. Without the stimulation of light and sound, my mind turns over thoughts and stories on repeat, revisiting inconsequentially boring past moments like a mantra: Did Xinghai think I was a jerk because I didnt say thank you earlier when he dropped me off? Did I end my e-mail to Gu in the wrong tone? What if I get stuck in this village forever? How slow would I be at harvesting rice? I get bored with my own thoughts and download a night-light app on my phone after scrolling through pages of App Store reviews.

Why are you here? One of my hosts, an old rice farmer, asked me this earlier. I had been traveling for days, and in my exhaustion, his question took on a more existential note. It took me a minute before I could sputter, Im here to see you.

I felt the pull of rural China about three years ago, after visiting villages in Guizhou, seeing a side of China very different from the one portrayed in most forms of media. This pull was amplified by my need to challenge my own metronormativitya portmanteau of metropolitan and normative, coined by the theorist and scholar Jack Halberstam.

Metronormativity is pervasiveits the normative, standard idea that somehow rural culture and rural people are backward, conservative, and intolerant, and that the only way to live with freedom is to leave the countryside for highly connected urban oases. Metronormativity fuels the notion that the internet, technology, and media literacy will somehow save or educate rural people, either by allowing them to experience the broader world, offering new livelihoods, or reducing misinformation.

For me, challenging this metronormativity is crucial. So much of the extended crises and the rise of authoritarian populism throughout the world has been a result of globalization. The urban-rural dynamic is central to globalization, with rural areas serving as the engine, the site of extractive industries from industrial agriculture to rare earth mining. I believe our ability to confront metronormativity will determine our shared future. We are intertwined across cities, villages, and national boundaries, bound by material circumstance.

I have traveled to rare earth and copper mines in Inner Mongolia, driven along dusty highways past wind turbines and data centers, visited villages where artificial intelligence training data is made, and seen empty villages where all the young people have left for electronics factory jobs in cities. Rather than seeing the way technology has shifted or produced new livelihoods in rural China, I have been humbled to see the ways rural China fuels the technology we use every day, around the world.

Questioning metronormativity means demanding something outside the strict binaries of rural versus urban, natural versus man-made, digital versus physical, and remote as disengaged versus metropolitan as connected. To question metronormativity demands a vision of living that serves life itself, and not just life in cities. Embarking on this line of questioning demanded a big change in my own core beliefs.

The dynamics of rural China are not isolated to China itself. Yet because of its geographic distance from the United States, it remains a kind of periphery. These rural peripheries, the edges of the world, hidden from view, enable our existence in cities. These areas produce everything from the cotton in the clothes we wear to the minerals that create the computers in data centers. They also produce the food we eat. It is impossible to disentangle the countryside from foodfood is at the core of the dynamic between the rural and the global. As humans, we eat to survive, and our appetite for food has carved new geographies and technologies into the world. Urbanite appetites, especially, have shifted rural economies, ecologies, and societies over the past three decades.

I have a difficult time grasping the full dynamics of complex concepts like climate change, which creates economic and ecological relationships at a dizzying array of scales throughout the world. Yet agriculture and what we eat are tangible manifestations of these entangled global issues that affect all of us. According to a recent United Nations report, a third of human greenhouse gas emissions stem from industrial agricultural practices. These same industrial agriculture practices have rearranged the way rural communities live, fomenting political change around the world.

Conducting research in rural China meant that I could, selfishly, return to villages that I love being in. There was an allure to living at a pace and scale that felt comprehensible, to living in a place that felt grounded. It is easy to romanticize rural Chinese villages as idyllic scenes of nature, small and disengagedyet many of them are sites of economies and agricultural practices that are foundational to our world. And as numerous historians, such as Robert Brenner and Sue Headlee, have shown, shifts in agriculture and rural politics were crucial for the transition into industrialization and capitalism throughout the world. In thinking through agriculture, through a sense of place and belonging, I was influenced by the writings of bell hooks and Wendell Berry, for whom being and belonging acquire a sense of urgencyespecially in a political and economic system that dislocates people from place and community. It would have been easy to attribute the loss of belonging, of place, to just technology accelerating us into the singularity of despondency. But challenging my metronormativity meant challenging these ideas of the digital world versus the physical world, and pulling back the idea that becoming a Luddite and disengaging is the only way to reclaim a sense of belonging.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside»

Look at similar books to Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Blockchain Chicken Farm: And Other Stories of Tech in Chinas Countryside and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.